A simple snorkel is enough to enjoy the reefs.

Without edges, almost spherical, to take advantage of the currents, hollow inside to float, and with skin as hard as ebony to protect the seeds, coconuts are true highly engineered ships, capable of navigating, dragged by the invisible conveyor belts of the sea, thousands and thousands of miles, the entire ocean if it were to arise, before settling and taking root in the apparently barren sand of who knows what beach. I look at the small trunk, barely four inches, that emerges from this coconut. Where will it come from? Bora Bora...Hawaii...Acapulco? Seeing the destiny of this palm tree, on a beach of pinkish tones of a small Polynesian island, I find compelling reasons why I do not mind being a coconut in a supposed next reincarnation.

A long time ago, just a few days actually, but they already belong to another life, it would not have occurred to me to think in these terms. Of course, I would not have imagined that sharks would be scared of a chihuahua, nor that ukulele music, in high doses, would sound so Christmassy –the air conditioning of the Air Tahiti Nui plane helps–, not even that the land of this island that I now walk on, idyllic as a child's drawing, was, in reality, coral dust. Coral sand resulting from the erosion of the barrier reefs that grow on the craters of an extinct chain of volcanoes drowned by their own weight tens of millions of years ago.

I do not take, as García Marquez would say, 'happiness as an obligation', but anyone who sees me here, at this moment, will understand that he has the right to feel that way. I am now finally beginning to understand that the privilege of traveling is not only about learning, but also about observing the environment from previously unsuspected perspectives.

Aerial view of Fakarava, the second largest atoll in the Tuamotu.

The infinity of scientific data, addresses and interviews with chefs and regular local personalities in my travel notebook are this time a succession of exclamations. I have hardly taken notes, I admit it. Nor did I know that a crazy Japanese, who else, has already invented the submersible notebook. But I return from the Tuamotu with a handful of anecdotes that will liven up the table talk, with recently discovered interests and, above all, with the senses relaxed, the soul appeased and the occasional revelation.

An atoll lost in the Pacific is a good place to order emotions. And what I've experienced, I don't forget, and that is... I never imagined that I would get used to swimming among sharks. None of the species of sharks that live in the waters of 'Tahiti and its Islands', and there are several of them, attack the man unless he feels threatened, and a threat of a slap makes them flee, but you run into the sharp smile of a shark, no matter how skittish it may be, is restless to say the least. And something else when there are four, six, ten, dozens...

At 28 meters deep, floating above a coral garden that concentrates all the colors of the universe, I direct my gaze in the direction that my diving instructor's arm points. Up there, a score of gray sharks surround a tuna in a circle. The light that penetrates from the surface gives the scene a patina of unreality. A school of tropical minnows parade in front of my glasses oblivious to the tragedy. They are followed by barracudas, trumpet fish, butterfly fish, snappers... Nature goes free. And my attention wanders.

The miraculous effect that 24 hours by the sea has on the gesture, on the skin, on the color of the iris never ceases to amaze me. The breeze wakes me up in the face. He dreamed that he recovered the affection of an old love. I open my eyes and see blue. I walk the two meters that separated me from the lagoon and dive into this natural aquarium. A manta ray says good morning to me. I feel like Mary Poppins jumping into a cartoon that becomes animated.

Dozens of sharks swim in the crystal clear waters of the Tuamotu.

The jet lag begins to wear off, and I remember the impressions of Bergt Danielsson, the Kon-Tiki anthropologist: “Purgatory was a bit damp, but the sky is more or less as I had imagined it”. Palm trees float on the horizon, as if in a mirage, their trunks hidden by the curvature of the world. Not a trace of the cruel nature and indifferent to human suffering of the stories of Jack London and the sailors who baptized this archipelago as 'pernicious'.

I haven't opened the suitcase yet. I don't think I do. In the simple life of the atoll hardly material goods are needed. A pareo and little more. Maybe a snorkel. And some flip flops. Neither hot nor cold. Neither early nor late. Time measurement, if any, only marks the time of scuba dives. But I am quickly getting used to this routine.

I never would have imagined that excess heat would be sustained as an argument to produce wine. But Frenchman Domenique Auroy saw value in high temperatures that kill the fungus that makes vines sick and decided, a little over a decade ago, to plant a vineyard on the coral land of Rangiroa: the first in a tropical climate. The secret? "You will understand that we have invested too much time and money to find out," he smiles mysteriously.

In the Vin de Tahiti cellar I find that the whites, perfect to accompany lobster and poisson cru (the national Polynesian dish, similar to ceviche but with coconut milk), taste of vanilla and coral; the fruity rosé, fresh, easy as a juice; and the red... Do you have a Hinano beer, please?

I never would have imagined that a piece of sliced bread and a piece of string, just a bit of thick dental floss, would be enough to catch food for 16 hungry 'sailors'. My companions on excursions to the Blue Lagoon – all the islands have a ‘blue lake’, sometimes even a green one – curiously crowd around the first catch, throwing the small boat off balance. One by one, children first, we all want to try our luck (because it does not imply skill) and proudly photograph ourselves with our prey. Such ease arouses my suspicions. Already on the shore I reflect on the chances of survival I would have on an island like this. I'm afraid not many. Where would you get the fresh water?

A bell through the palm grove interrupts my dilemma. "The food is on the table," announces a large, robust man, while he stirs up the embers that brown the formidable mahi mahi specimens with an elephant ear leaf. Hundreds of baby sharks, babies and adolescent blacktip sharks, so small and perfect that they look like bathtub toys, swirl expectantly on the shore of the green lagoon. They know that the remains of the feast will be for them.

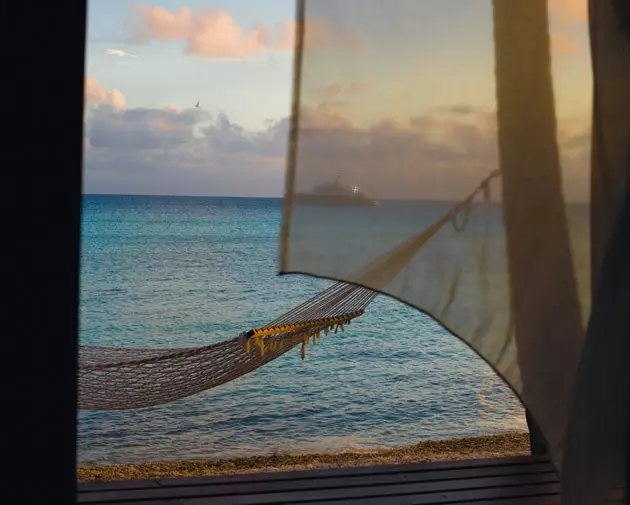

The pink sunset on a Rangiroa beach.

I never would have imagined that the heart of the Polynesian black pearl would be brought from the Mississippi. The Gauguin's Pearl farm guide, a beautiful young woman with pearly skin, explains to me the reason for the fascination with this jewel and the cultivation process thanks to which the gonad of an oyster generates mother-of-pearl, the precious mother-of-pearl, as a defense against an element strange (in this case, a piece of yellow mussel shell from the American river) .

I pay attention to the meticulous surgical operation, but I can't get Mark Twain out of my mind during his misadventures in the Tuamotu. Surely he had a perfect pearl in his pocket, a gift from a one-eyed scoundrel, grateful for saving him from that bar brawl.

I did not know that meat consumption could be so high on a motu where, wherever you are, you can hear the sea. Although I suppose he has the logic of it. Boxes of meat from New Zealand pile up in the port of Rotoava, Fakarava's main town (there are only two). It seems that there is not much activity tonight, but the arrival of the cargo from Tahiti is usually the big event – in the atolls without an airport, all but three, it is the only connection with the rest of the world.

Fakarava not only has an airport and an international-class hotel, Le MaiTai Dream, but also an illuminated highway. They owe it to Jacques Chirac. They were waiting for him for lunch, maybe he would stay for the cafe, but he never came. The brand new road, 40 km uninterrupted with those who wanted to welcome him, nevertheless encouraged many of the 712 inhabitants of the atoll to buy a car. I prefer to travel it by bicycle. And stop at the fruit stalls and at the houses of those children with whom I do not share a language and who give me a black pearl in the shape of a heart.

I know it's one of those magical moments before it happens. The furious barking of the dogs question my good idea, but the starry night invites me to walk it, and Paul Gauguin's self-prophecy convinces me: "in the silence of the beautiful tropical nights I will be able to listen to the sweet music whispered by the movements of my heart" . The wind rocks the palm trees and, as if they were dancers with straw skirts, the choreography begins. The 'hips' on one side, the raised 'arms' on the other.

Now I also know that paradise exists and that I would like to take root in it and learn to dance with the coconut palms. But I have to leave Eden and I do it as Ulysses left Calypso: grateful, but without love. Although here, now, I can not complain.

This report was published in issue 32 of Traveler magazine.