Fernando Fernán Gómez and Jorge Sanz in 'Belle Époque', by Fernando Trueba (1992).

In journalism we are hanging from hangers, from excuses, from the newsworthy, from the supposedly extraordinary. For example, we hooked on centenarians (whether death or birth) as a subterfuge to launch headlines about someone we could be talking about constantly and at all hours, but we tend to corner in the event. Today it is Fernando Fernán Gómez's turn because on August 28 he would have turned one hundred years old (like Saura's mom) but now that I read him again, that I revisit his movies and I get lost on YouTube following the trail of the comic side of him, his loquacity and his temperamental character I come to the conclusion that in the deafening informative nonsense of every day we should open a constant crack for his words: a crack for Fernando by decree and by necessity.

Reserve a fixed corner for his bittersweet lucidity, for his tragicomic vision , balloons and horror (I'll explain later) like someone looking in a mirror that only tells the truth. (Fernando's bot? The hour of the resurrected?). And so we could easily forget about the hangers. Or almost. Because Fernando Fernán Gómez (and forgive me for being frivolous) was never handsome, but he was a man with a very good hanger. He was tall for a Spaniard born in the first half of the 20th century. (he was one meter eighty-three) and he was also extremely red-haired, which is another of the rarest things a Spaniard can be.

He was also an illegitimate son, like Threshold (I'm not sure if it's something very Spanish or not) and, despite being a scholar and an intellectual, he always did his best to hide it, although it must not have worked out all that well because after writing 36 screenplays for film and television, 13 novels, 12 plays, two collections of poems, a dozen books of essays and innumerable 'thirds' of the ABC newspaper, he ended up occupying the 'B' chair of the RAE. Still, he always played it down. He always doubted. Which obviously, and luckily for us, did not subtract an iota of productivity.

The world goes on (Fernando Fernán Gómez, 1963)

He must have spent many hours alone to write such a work (so many pages, so many words, so many voices) and yet he always gave the impression of being a man of a troupe, of company, of revelry, of hubbub, at night, gathering, bread and whiskey. A walking hyperbole, a comedian as angry as he is tender, a shy seducer, who he came to make 210 films as an actor and 30 as a director, including two masterpieces: The strange trip and Trip to nowhere, that dusty jewel about the hardships that the members of a company of post-war league comedians (that decade of the 40s, so Spanish and so hungry). A tour through the Castilian steppe, a journey to no glory, raising scenes from town to town in depressing places, in stables tidied up for the occasion, sleeping in sordid, seedy and filthy inns, so Spanish.

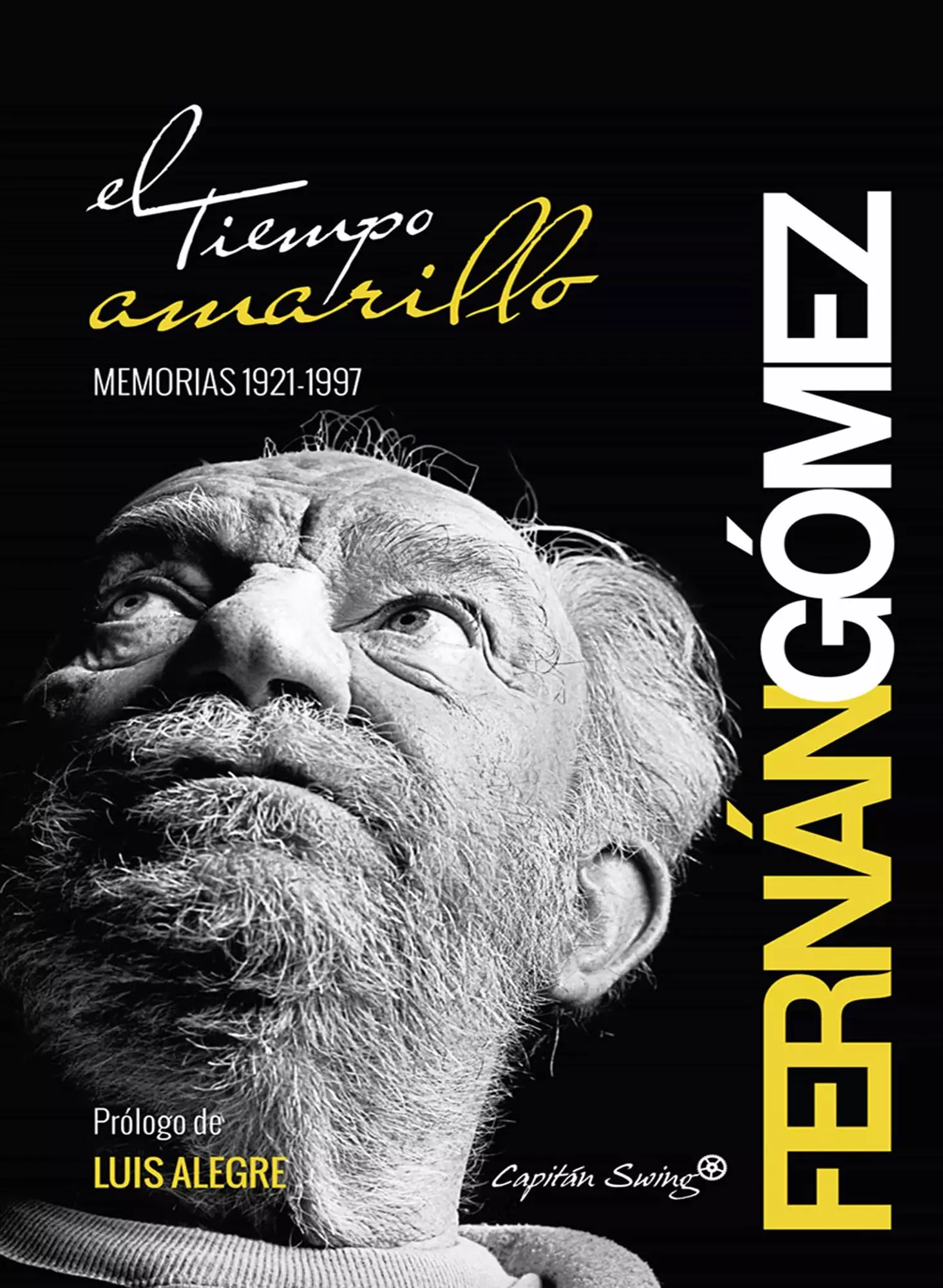

Dragging the suitcases, the trunks, the props, dragging the passion and the profession and the dignity and the integrity and the desire to eat. An acid, funny and hurtful story with an autobiographical aroma that is so reminiscent in its lyrics, but above all in its tone, another of the capital works of Fernando Fernán Gómez, his own autobiography, El tiempo amarillo (Ed. Capitán Swing), where he recounts the "current" circumstances of his arrival in the world: "I remember reading I don't know where that one shouldn't write about one's own childhood, because the childhood of all men is the same. Indeed, I was born, like everyone else, in Lima. But they didn't register me there, but, like all men, they took me out of Peru almost by smuggling, because the company in which my mother performed continued its tour, and I was registered days later in Buenos Aires. My grandmother, like the grandmothers of all the others, had to move –at her sixty years as a seamstress from Madrid– to the city of Plata to take charge of the event, since my mother had hired another nomadic company, that of Antonia Plana and Emilio Díaz, and she did not know what to do with that gift from Providence”.

Still from 'The Strange Journey' (1964), directed by Fernando Fernán Gómez.

That gift of Providence, unrecognized son of María Guerrero's son, he wanted, like his mother (and like his grandmother with whom he never spoke), to be a comedian, and during the Civil War he studied at the CNT acting school. He made his professional debut in an anarchist company in 1938, because in the rear of Madrid the bombs fell but there were also two daily functions in all theaters. And there Jardiel Poncela discovered it (another that we should talk about every day by decree and necessity) who gave him his first opportunity with a role as a supporting actor in Los thieves, we are honorable people.

Worker and patrician of show business at the same time, Fernando was always pragmatic and not at all solemn. In fact, he bragged about not choosing the movies and only put some basic conditions to accept a role: to have free dates and to be paid his salary. Perhaps that is why he also participated in some of the funniest films of Spanish cinema such as Growing leg, shrinking skirt, Finer than chickens or Las Ibéricas F.C., stories about very horny gentlemen and very naked ladies who, despite their dandruff, also pushed our bodies towards democracy.

And that was not his only contribution to our historical maturation: Fernando also made The Spirit of the Beehive and Mambrú went to war. And he wrote what is probably the most important and realistic work on the intimate experience of ordinary people in the Civil War: Bicycles are for summer. Because Fernando was a strange man who understood human nature with mercy but without a moral, which is as much as to say the nature of art.

Cover of the memoir of Fernán Gómez.

He demonstrates it in that wonderful childhood scene that he recounts in The Yellow Time, about the balloons and the horror that he told you at the beginning. There he tells that one Thursday in the winter of 1929 he witnessed the most dramatic scene of his life: “The maid, the young, pretty and flirtatious Florentina was not at home. She must have been very close to dinner time and she rang the doorbell. Grandma Valentina got up from her chair and wearily went to open the door. As soon as she opened the door, a horrific, high-pitched scream was heard. It was Florentyna who was screaming, on the landing of the stairs. In one hand she was carrying some packages and in the other she was holding the colored balloons. Her cheeks were wet with tears. Without stopping screaming and crying, she rushed like a whirlwind down the hall. After her we all went after her who, in a race, she turned the corner of the corridor and went into the bathroom. She there she fell on the toilet bowl. We go to the door. Florentyna, spread-eagled, was still holding the balloons in one hand. of colors and between tears and screams she told us that her little niece, her little one, four years old, had been crushed by a car ".

She "she told it over and over again, sitting on the toilet, without letting go of the balloons, without stopping crying and screaming. The toilet, the spread legs, the colored balloons, the screams and the tears must have made a very comical picture, but Neither Grandma Valentina, nor Manolín, nor Carlitos nor I laughed. We were watching a drama. (...) What was dramatic –Fernando continues– was the dead girl crushed by the car, the tears and the heartrending screams of her unfortunate aunt; the funny thing was the colored balloons, the toilet. If a comic author had worked on this situation, he would have transformed the girl's death into a simple bump on the head; and the piercing screams and the maid's tears would have been turned into comically ridiculous moans. Instead, he would have kept Florentyna sitting on the toilet with the colored balloons in her hand. If a playwright had worked on the same situation, the maid would have come to the house only with the packages, without the colored balloons, and she would not have dropped on the toilet, but on any chair, and there she would have screamed heartrendingly and given free rein to tears and the paragraphs. But reality does not proceed like this, it does not select, it adds the heartrending screams with the dead girl, with the balloons, with the car, with the tears, with the toilet”.

Fernando Fernán Gómez and Leonardo Sbaraglia, 'In the city without limits' (2002)

Yes, I was right reality is an incoherent sum of things that happen and happen to us, of balloons, toilets and death. There is no tragedy or pure comedy. That is the journey.

When Fernando Fernán Gómez passed away in 2007 I felt that someone had left home. Someone very mine. Someone unbreakable who in his old age looked like a thunderous God, Valle Inclán or Don Quixote. Almost always we believe eternal, like a rock, who was already here when we arrived to the world. And I wanted to fire him.

His funeral chapel was open all night at the Spanish Theater, and my partner at the time and I approached late, with shyness and admiration to watch over Fernando's coffin, covered by an anarchist flag. Time after I wrote this poem, I hung it on a book hanger and there she stood, trembling.

BURNING CHAPEL

The night Fernando Fernán Gómez died

we made love on the couch.

We walk hand in hand on the cobblestones of Juanelo

and we excitedly approached the Spanish Theater.

Celebrities swarmed on stage

and we stayed in the stalls,

hoping for,

with the docile habit of the spectator.

A man, another stranger, like you and me

read a poem on a photocopy.

I didn't write anything in the condolence book,

What was he going to say, that he was happy?

Floor clause. Ed. Huerga and Fierro.