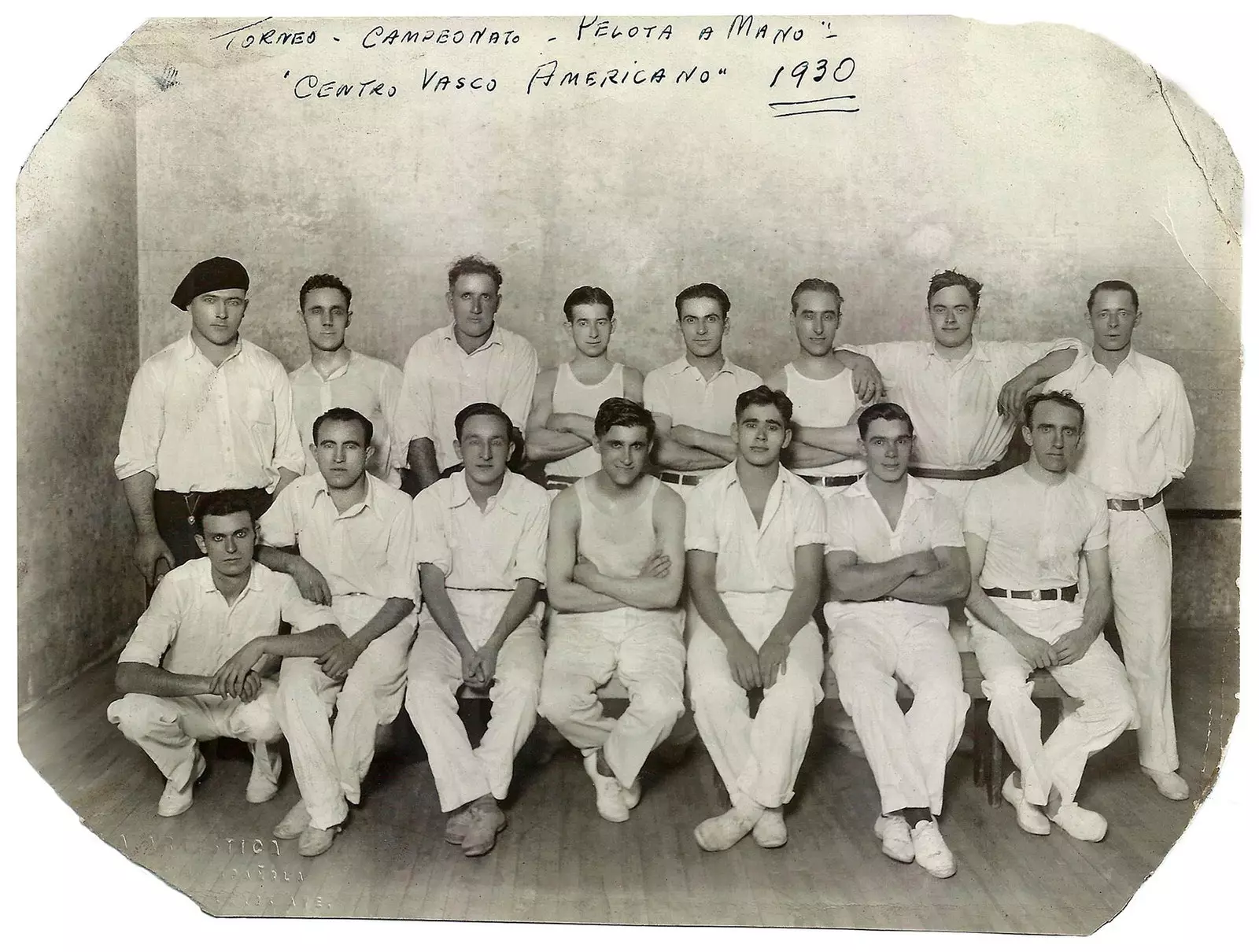

"My grandfather Adolfo is the one in the center, with a black beret. He arrived in 1926 and worked as a stoker in Newark, New Jersey. In four years he saved what he needed to buy a house and land in Galicia." Joe Losada

Almost a decade, against the clock, without rest, they were Professor James D. Fernández and journalist and filmmaker Luis Argeo documenting an episode of Spanish history not so well known: that of the thousands and thousands of Spaniards who left their towns and cities for the United States between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. And in many cases, the majority, they did it without a return ticket.

“We have traveled from coast to coast of the United States and also through Spain with portable scanners, computers, cameras, microphones, entering the houses of strangers who they invited us for coffee while we scanned their family albums, in which we not only found wonderful images from 80 or 90 years ago, but also personal, family stories that were about to fall into oblivion,” explains Argeo by phone.

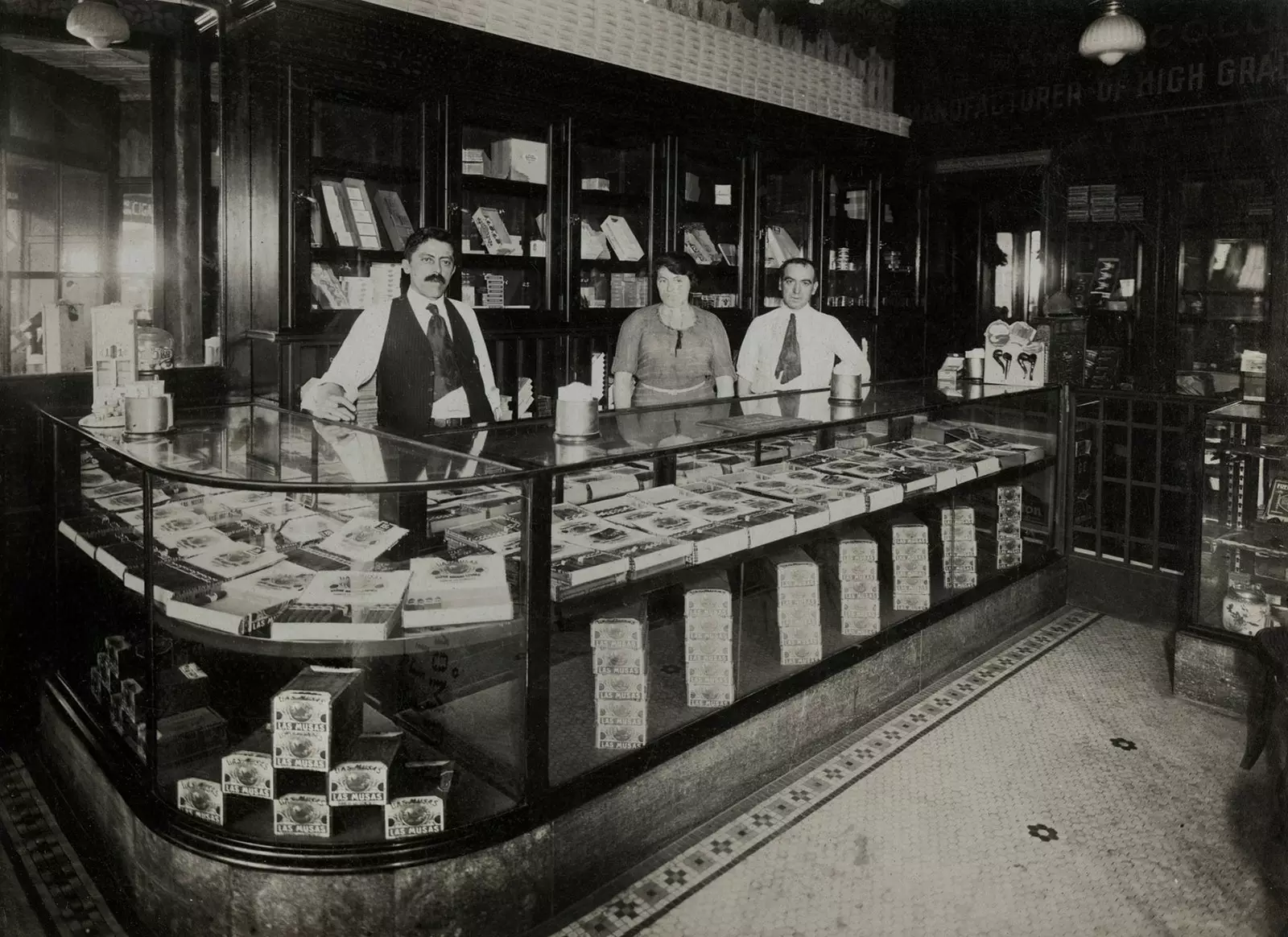

The counter at Las Musas cigar store in Brooklyn, New York.

A job they did against the clock because the descendants of those emigrants "are people of advanced ages" and with them the stories and memories of their ancestors will go.

After a book and several films, among the more than 15,000 materials recovered in that time and those visits, they have made a selection of more than 200 digitized files and 125 originals that can be seen in the exhibition invisible migrants. Spaniards in the USA (1868-1945), promoted by the Spain-USA Council Foundation, at the Conde Duque Cultural Center in Madrid from January 23.

“We have reached today with the urgency of telling about it before we can no longer do so with the same rigor that we have followed thanks to the testimonies that, although fragile, either due to memory or the material state in which we find them, they are almost on the verge of disappearing”, continues the documentary director.

“That is what we want to reflect in the exhibition: that it is possible to know the phenomenon of emigration to the United States from personal stories, family microhistories; that by uniting them all we can understand a little better this historical episode that, unfortunately, has not received all the attention that we believe it deserves”.

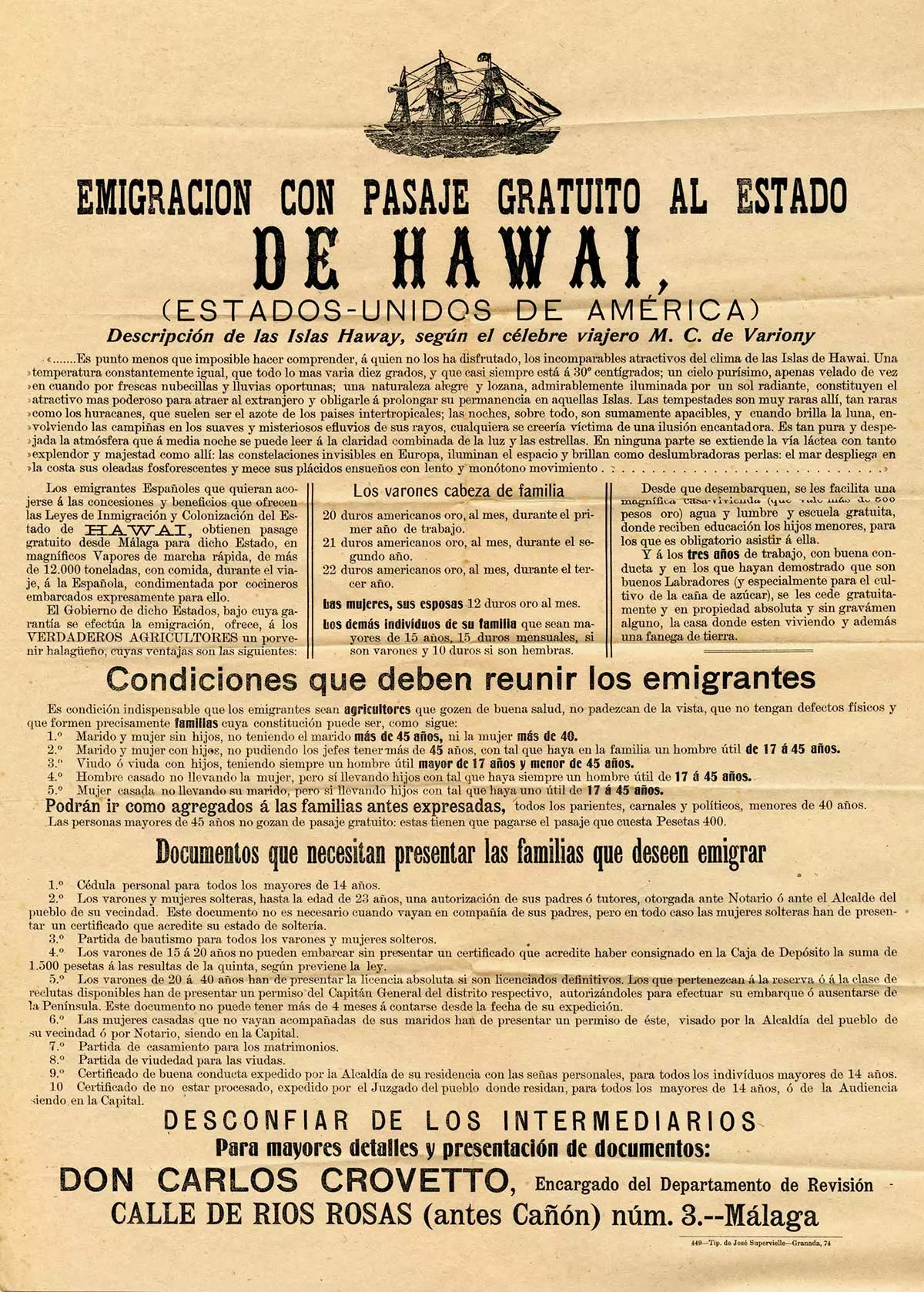

Original poster spread in the south of Spain after 1907 to recruit families destined for the Hawaiian sugar cane plantations.

MORE THAN ONE LITTLE SPAIN

Asturians in the mines of West Virginia and in the factories of the Rust Belt, Andalusians in Hawaii's sugar cane plantations and, later, in the fields and canneries of California; Basques in the pastures of Idaho and Nevada; Cantabrians in the quarries of Vermont and Maine; Galicians and Valencians in the New York shipyards; Asturian and more Galician in the tobacco companies of Tampa.

There were many more Spanish communities in the United States than we usually know on New York's 14th Street. “We have found representation of all the points of the Iberian Peninsula”, highlights Argeo.

But how did a man from Granada and a man from Zamora get to Hawaii? For all those Spanish emigrants “His homeland was work” say the researchers and curators of the exhibition. “They moved based on the trades they performed. It was a period in which the United States demanded a lot of labor and before the immigration law, they came and worked directly.”

To Hawaii, for example, "there were about 8,000 between Castilians, Andalusians and Extremadura", he answers. “The agents for the Hawaiian sugar companies were determined to get rid of the Asian workforce, they wanted to whiten the islands a little bit, and they came far enough that the hired people wouldn't have the idea of going back, plus they wanted qualified people who knew the trade, and in Granada and in the south of Portugal they found plantations”.

New York, 1939. Goofing around on the grass.

Although among those 8,000 who left there were also many who, due to the famine in Spain, had never tasted sugar. “These companies came with seductive a priori offers: they gave them a house, more money if they went with their family, even a piece of land if they stayed for more than five years…”, he continues.

There was a call effect, although later they were not as pretty as they painted: "They did not keep their word and almost 80% of those who left jumped to Steinbeck's California, that of fruit picking: we have found very Grapes of Wrath photos”.

Another interesting focus was on the American East Coast, in Tampa. “There we found another entry of Galicians and Asturians who emigrated first to Cuba, where they learned the trade of tobacco workers –in many cases, from compatriots– and then jumped to Florida to continue doing the same and They turned a small fishing village and 500 inhabitants like Tampa into the tobacco capital of the world.”

A JOURNEY IN STAGES

**The exhibition (from January 23 to April 12) ** is organized in six chapters which correspond, as Argeo points out, to the episodes in which the migratory odyssey of these people used to be divided. The first episode is 'The good bye': "They say goodbye and take photos of the relatives who stay in Spain or of themselves before leaving, passports...".

The American Basque Center, on Cherry St, New York, had its own pediment.

In a second 'To work' They show through these photographs and found materials "a journey through the different trades and regions". In 'living life' they show how their life there “wasn't just work”, they talk about leisure, their free time and how they related between communities.

'They got organized' It is the fourth chapter of the show, in which they talk about social clubs or charities. In 'Solidarity and discord' They arrive at the Civil War, a moment that for many meant saying goodbye to the idea of returning to Spain, either because of political ideas or because of the economic situation of the country they had left.

Resigned to stay in the United States, they raced to integrate or have their children integrate: it is the chapter of 'Made in USA', where they speak "of that cultural assimilation, application for nationality and pushing their children towards a new model of life." Children and grandchildren who, for the most part, do not even speak Spanish today.

Poza Institute of Languages and Business, New York, c. 1943.

"This is one of the problems," Luis Argeo points out, "that, with that assimilation, when his parents push them to be more American, they learn English, study for a degree, and loosen ballast... Spanishness becomes something very familiar, from the private environment and they are losing it".

And yet, they have found people, grandsons or granddaughters who have started to learn Spanish because they decide to look back. "They want to know the life of their relatives: why the grandfather had such a strange accent, why Spain was never spoken in my house... It is the grandchildren who are trying to recover the lost footprints to get to know each other a little better”.

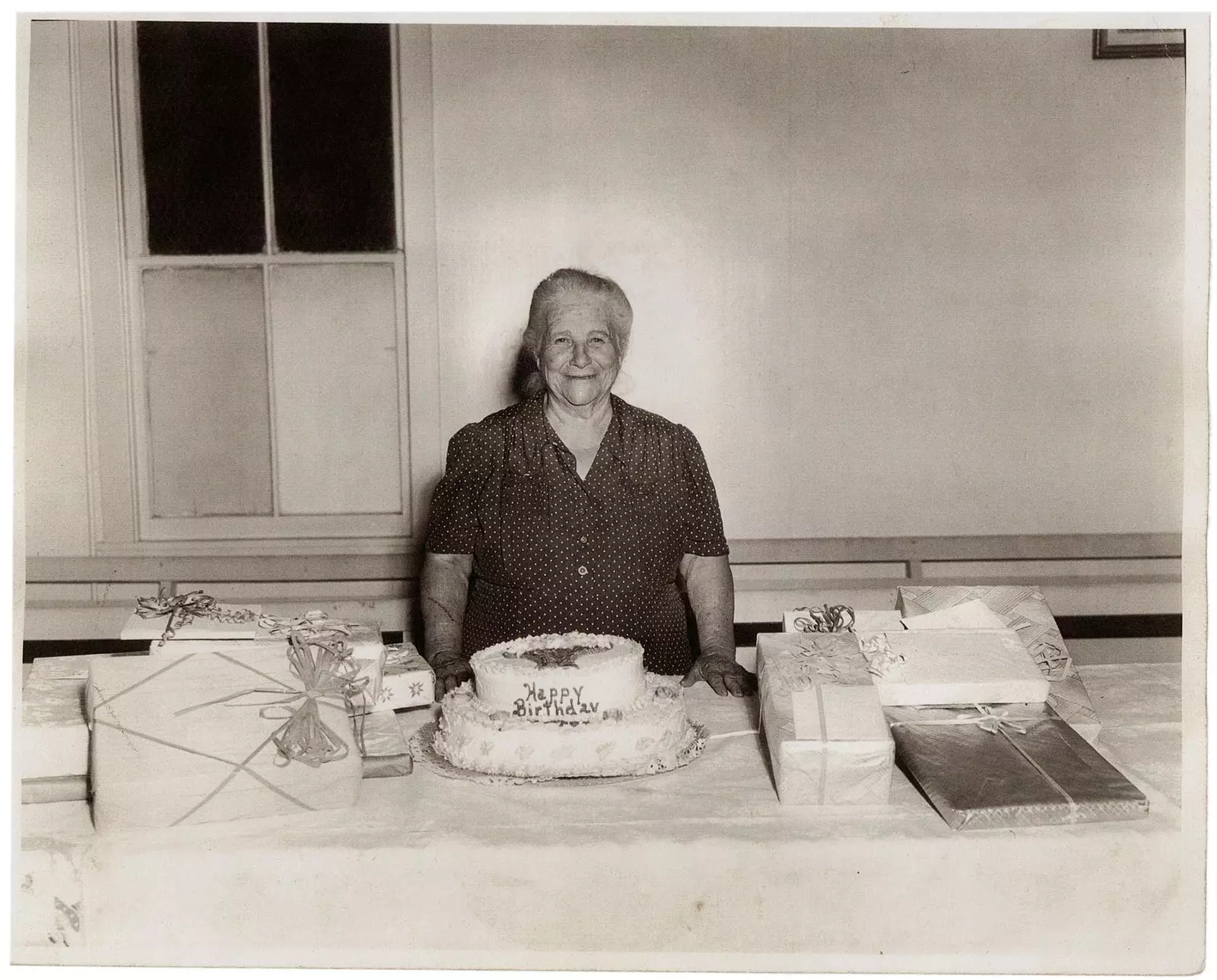

Japan Berzdei! «My great-grandmother, born in Itrabo, Granada, celebrates her 80th birthday with a cake prepared by her grandson, her pastry chef, and Californian, my father». Steven Alonso.