One, abstracted; the other, tormented

It is difficult to write about a figure like Leonardo da Vinci because everything is already said. The fifth centenary of his death and the deflagration of the Salvator Mundi at Christie's have generated a current demand that has been reflected in the recurrence of false myths about the artist and ** samples of varied rigor **.

Before venturing into fabulations, it is convenient to go back to the basics, that is, to the work. Listing Leonardo's creations, an indisputable statement emerges: the genius of the creator. Few reach the podium; in genius there are degrees.

The scale starts with artistic sensibility , which predisposes to creation. He is followed by talent , which allows to shape a relevant artistic expression. The genius , or the transcendent creation without predetermined rules, hides in the last rung.

As the charisma , genius is a manifest quality. Talent can remain in a game, and requires a suitable environment for its development. The genius finds a way that oscillates between fizz and eruption , and often leads to imbalance.

The Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo's most ambitious work

To this concept, formulated in the century XVIII , were added from Romanticism a multitude of connotations that have shaped models, topics or clichés, applicable to what we consider "genius". The square in which Leonardo falls becomes visible when contrasted with the one occupied by a young competitor who emerged in his last Florentine stage: Miguel Angel.

LEONARDO, THE ABSTRACTED GENIUS

Art, by definition, is not reality. The cliché of the clueless genius it is a consequence of his detachment from everyday life. Visionaries do not do the shopping, nor do they deal with the administration. are beings platonic who live in the world of ideas.

vasari , the artist biographer of artists, states that while Leonardo was painting The Last Supper , the prior of Santa Maria delle Grazie constantly pestered him to finish the work, finding it strange that an artist should spend half the day lost in thoughts of him. He adds that the religious would have wanted that he would never abandon the brush, just as those who dig the earth of the garden did not rest.

In the Piazza della Scala, in Milan, Leonardo is represented like this

Given his complaints to the Duke of Milan, Leonardo explained to him how men of genius are really doing the most important thing when they work the least , since they meditate and perfect the conceptions that they then carry out with their hands.

This reflective attitude was not limited to his hours among the pigments. It was continuous. Vasari says that Leonardo was so pleased when he saw curious heads, be it because of their beards or their hair, that he was capable of continue for a whole day who would have called his attention for this reason.

On the other hand, his view of his art prevented her from finish works that he had begun, for he felt that his hand was unable to add anything to the creations of his imagination. His mind conceived ideas as difficult, subtle and wonderful, that he thought his hands could never express them.

The testimonies of Vasari, who grew up in the 16th century Tuscan art setting and that, therefore, he had access to people who knew the teacher, show that his genius dwelt on the plane of ideas.

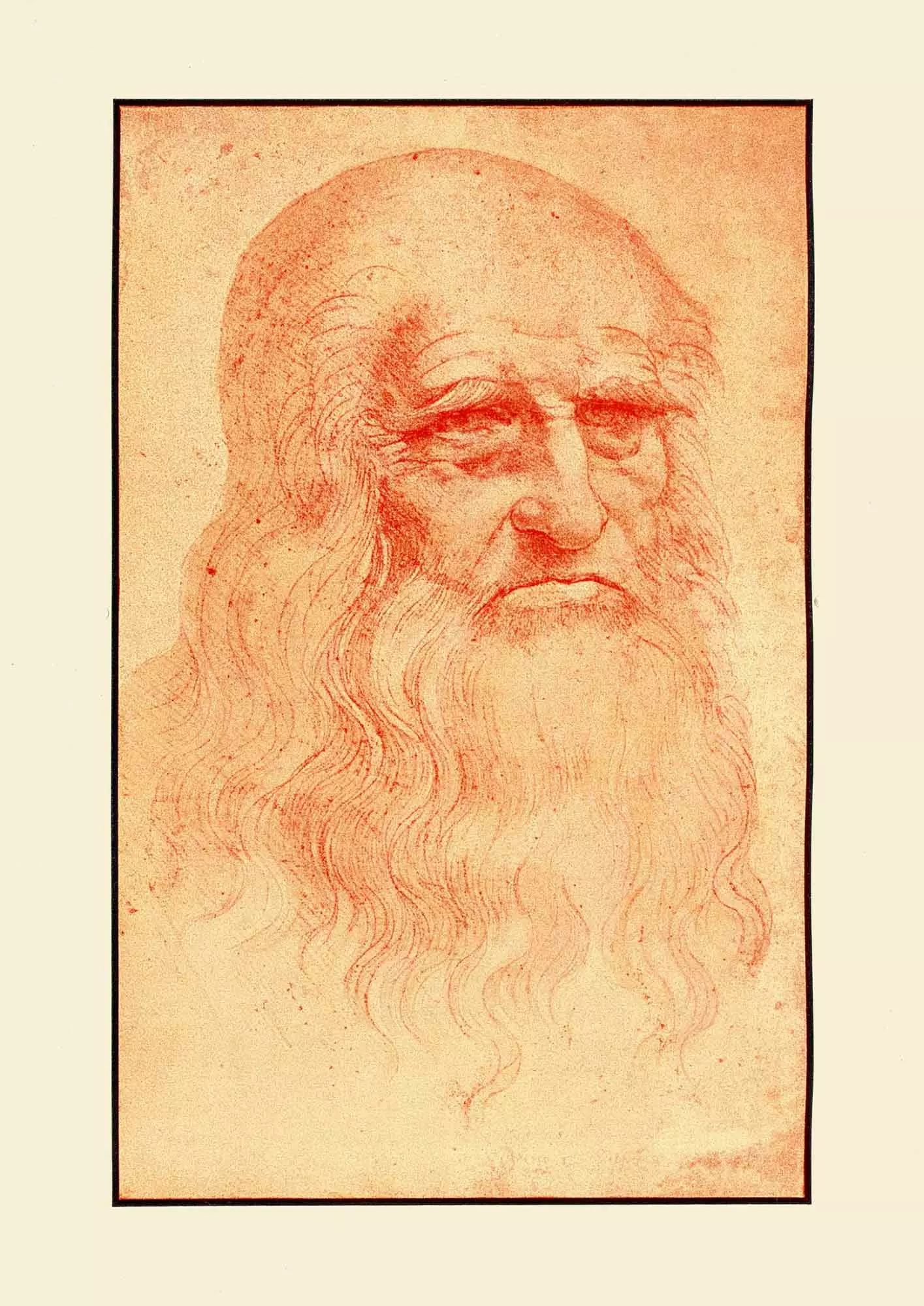

Thinking of Leonardo, we inevitably imagine a old man with bushy beard and meditative expression , a bit sullen. This image is highly conditioned by the assumption Turin self-portrait , which identifies you in manuals and catalogues. However, the artist died at sixty-seven, so he did not reach the age of the man depicted in the drawing.

The character that Vasari describes for us projected a great charisma; and he was attractive, personable and a brilliant conversationalist. Although the biographer seems to exalt himself in the description of him, it is not probable that he fabricated a false image: Leonardo was not a hermit. The biographical ups and downs of him and his courtly role They anchored him to reality.

Faced with doubts about the identity of the Turin drawing, the portrait that his disciple drew Francesco Melzi it offers the security of attribution and an aspect that fits Vasari's testimony. That is to say, an abstracted genius who made use of his talent and his personal charm to negotiate with reality.

The supposed self-portrait of Leonardo

MICHELANGELO, THE TORMENTED GENIUS

A generation after Leonardo, a figure emerged who embodies the model of the genius as we conceive it today . The figure of the abstracted sage that Leonardo embodies tends to be identified with the overthinking that accompany scientific thought. Faced with this intellectual work, it is assumed that the passage to artistic creation implies a certain internal conflict.

Already in the 16th century, Vasari affirmed that most of the artists who had existed until then received from nature a dose of madness and wild temper , which in addition to making them sullen and capricious, had given occasion for the shadow and darkness to be revealed in them many times.

Although he was not referring to Michelangelo, whom he knew personally and to whom he professed a deep devotion, the reference is evident. Leonardo had the ability, or inclination, to cultivate abilities that they pleased the princes of the time. He was beautiful, wise and moderate in dealings. Michelangelo, on the other hand, maintained a precarious balance with power.

Paul Giovio , the artist's contemporary who published his biography, claims that Michelangelo was rough and savage. He lived with great austerity , he did not give importance to the way he dressed and he hardly ate and drank. His character made him lonely.

In the Uffizi gallery, this is how Michelangelo is portrayed

To this Vasari adds that, when he began work on the Sistine Chapel, he had his assistants work on some figures as a trial, but, seeing that his efforts fell far short of what he wanted, he resolved erase everything they had done and, locking himself in the chapel, he did not want to let them enter. Also he denied entry to pope Julius II, that he had to force the artist under threats in order to check his progress.

With this pope he had a tempestuous relationship. After one of the confrontations, Miguel Ángel sent a letter to his servant to inform him that, from now on, when his Holiness looked for him, he would have already gone elsewhere. But, despite his character, Michelangelo yielded ultimately. In the sixteenth century, the artist lacked autonomy . His Holiness had the last word.

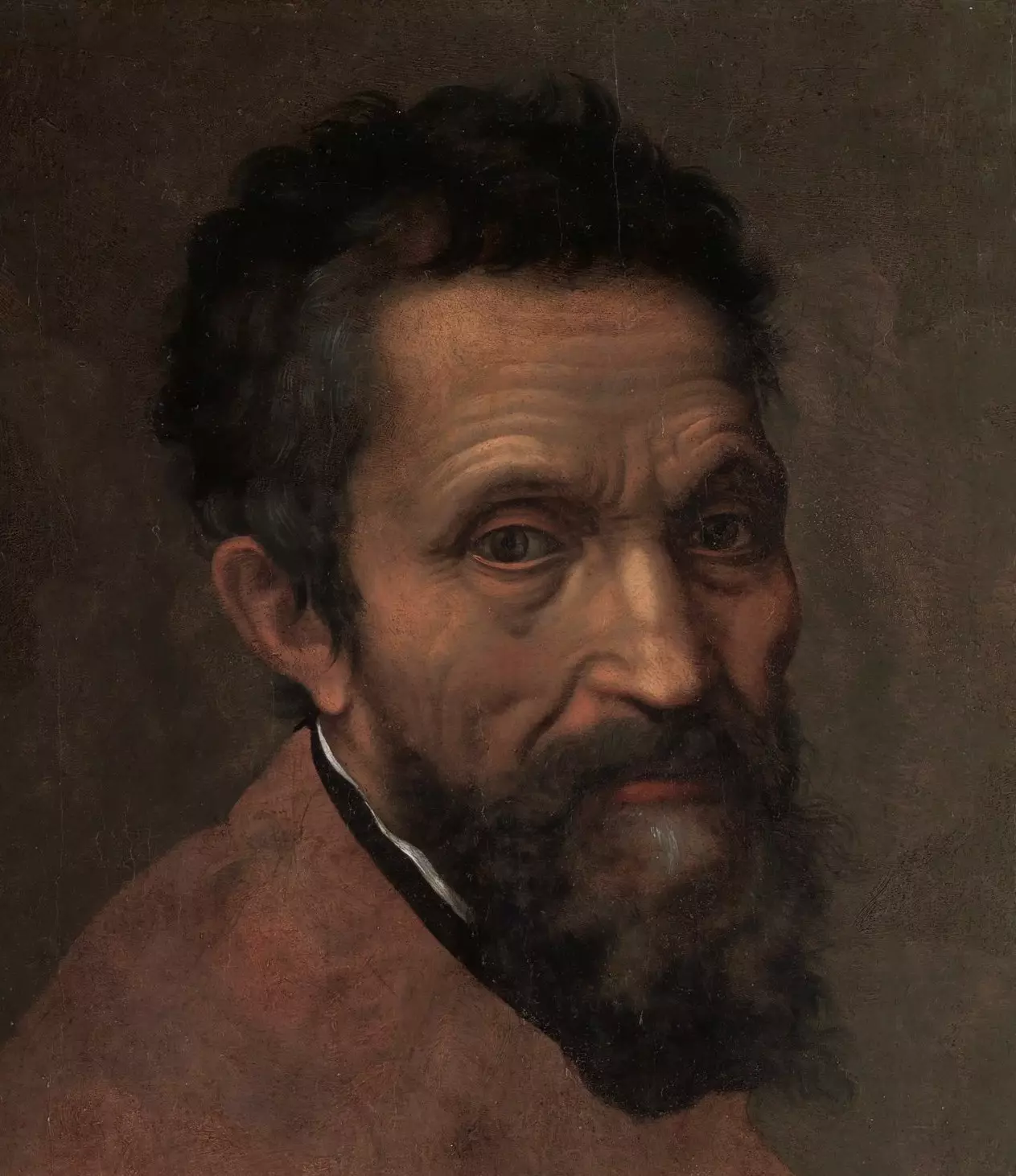

We have a portrait of the artist by Daniel of Volterra , one of his followers. In the image we contemplate an unattractive man, with a gloomy look and a melancholic gesture. The conflict that was established between his deep religiosity and the impulses that are reflected in the sonnets and madrigals that he dedicated to Tommaso dei Cavallieri they did not help mitigate a stormy character.

This is how Daniele de Volterra saw Michelangelo