Trip to a painting: 'Red Canna', by Georgia O'Keeffe

this is not a flower.

It is not in the same way as the painting in which Magritte painted a pipe it was not a pipe but a painting, and its author warned us so with a sign inserted in the very space of that painting: Ceci n'est pas une pipe , of course he left it.

And Magritte was not lying . Because neither the word pipe is a pipe, nor is the image that represents a pipe a pipe, nor is the idea that we have of a pipe, or of all possible pipes. Well, it is the same with the flower: as far as this is concerned, there is no difference between a flower and a pipe.

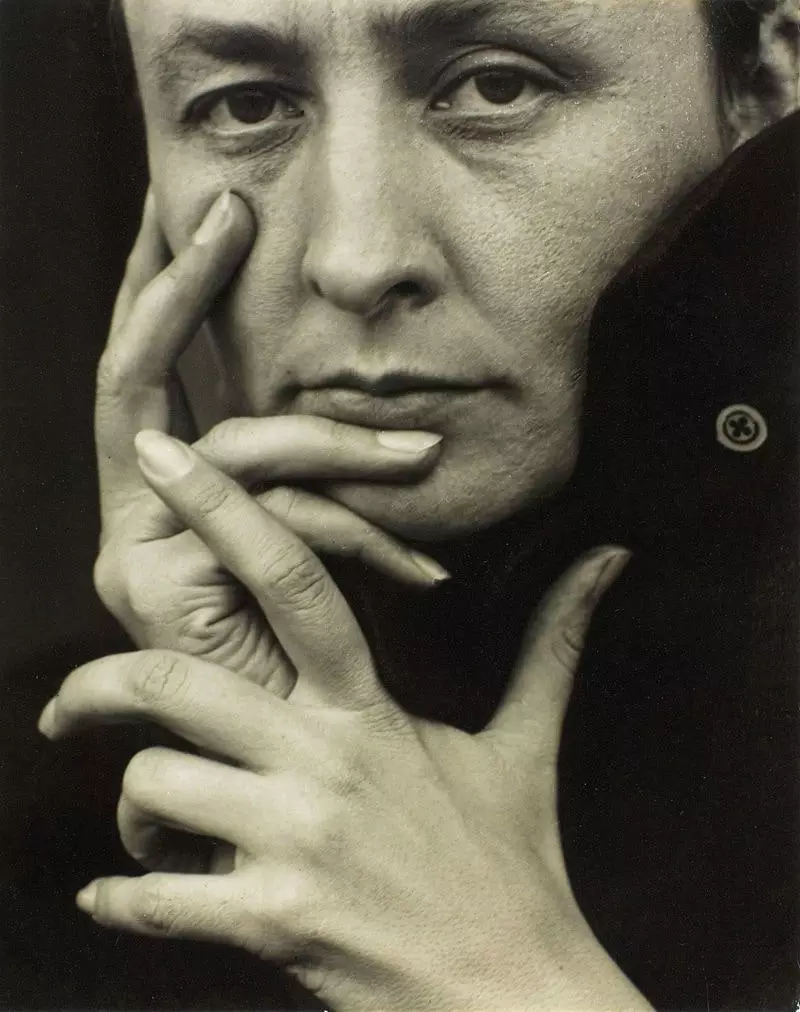

Georgia O'Keeffe in 1962

That this is not a flower does not mean that it is a female sex , which is what has been repeatedly said of the more than two hundred flowers painted by the North American Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986). Because it seems obvious and very Freudian that a woman artist portrays herself indirectly alluding to her own reproductive system . Also because the photographer Alfred Stieglitz , who was her gallery owner before becoming her husband, took it upon himself to encourage that interpretation. And, in case it wasn't clear, he underlined it in red convincing the painter to she will pose nude next to her own paintings in a series of photos that caused a sensation. This was already the lace, as they say.

It matters little that the most repeated thing in Stieglitz's snapshots is not the sex of the artist but her hands , and that often those hands remember precisely flowers raised on their stem . It seems even less important that O'Keeffe herself insisted that when she painted a flower she did not intend to execute sexual metaphors but rather to contribute to the forging of a genuinely American art (which would not be incompatible either). For the public, she was and always would be the painter of flowers that looked like genitals.

It must be said that this public was well educated and knew the history of art, and that is why they knew that in a painting a flower is usually something else as well. If we refer to the christian iconography , for example, the lily is the virgin mary purity and the red rose passion of christ . Any flower that appears in a baroque still life will be a warning that we too will wither as if our body were made of petals. In an impressionist work like the Monet's water lilies we will not have flowers but impressions of flowers. And Van Gogh's sunflowers and lilies they are above all an act of self-affirmation and thus reflect the tortured psychology of the artist.

We could go on, as there are plenty of examples: from floral garlands in the shape of Rubens border and the amazing compositions of Arcimboldo, Arellano, Ruysch, Brueghel or Bosschaert, to Fantin-Latour, Redon, Matisse, Isabel Quintanilla . To say of them that they limited themselves to painting flowers would be like saying of Hamlet that it is a ghost story.

In the seventies of the last century, Robert Mapplethorpe he also took to photographing flowers, perhaps hoping that the public You will appreciate the beauty of your previous nudes and stop seeing in them mere pornography with an artistic alibi. And what he achieved was exactly the opposite: thanks to him, it is now difficult for us to contemplate a calla lily or a tulip without finding sex appeal in them.

O'Keeffe photographed in 1918 by Alfred Stieglitz

It is conceivable that Mapplethorpe's flowers owe quite a bit to Georgia O'Keeffe's. And hers a lot to her years as a painting student of hers, when she began to paint them incessantly without finding what she was looking for . “Look at them well, and then she paints what you have seen”, they told her. And she did. She did it time after time, enlarging the scale like someone who has a microscope lens installed on the cornea, and that's when it worked.

That is why in his paintings we do not see a flower but what the artist has apprehended from a flower , and what she has felt in that exercise. “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose,” Gertrude Stein wrote in her best-known verse, but years later she added: “I am not an idiot. I know that in daily life we don't usually say this is this is this. But I think with that line the rose turned red for the first time in the history of English poetry for hundreds of years." Well, O'Keeffe, who was also anything but an idiot, invented with her painting a new way of looking at flowers, and that's why it was as if we were looking at them for the first time through her.

she explained Foucault in his book The words and the things that the world is governed by a succession of paradigms or imposed truths (“episteme”, he called this) that have delimited all the possible discourses and all the artistic works that we have been generating. During the time in which Velázquez painted 'Las Meninas', representation was in charge, but in the modernity from which O'Keeffe conceived his flowers there was no longer anything to represent, and in exchange there was much to analyze subjectively, that is, much to look at . So, if it no longer represents anything, what does a painting do? And why have we undertaken all the trips that have been proposed in this section?

I think that, to answer this, Bruno Ruiz-Nicoli and I could borrow the words of Georgia O'Keeffe herself. “When you pick up a flower and really look at it, it's your world for that moment,” he said. “ I want to give that world to others”.

Trip to a painting: 'Red Canna', by Georgia O'Keeffe