Torcello, the island where Venice was born

When one walks through Venice , crossing its bridges, looking out over its fondamenta and stopping at the campi, rarely resists the temptation to wonder what was going through the minds of the first settlers who decided build a city and carve out a future on the unhealthy soil of a lagoon.

Anyone accessing the city by train or car, or landing at the nearby airport, will quickly realize that Venice is not on the coast, not even a couple of kilometers out to sea: La Serenissima sits on the lap of the sea and surrounds herself with the waters trying to separate herself from the dangerous world that the mainland harbors.

Why turn your back on the continent and choose the marsh as a poetic 'hinterland'?

Why turn your back on the mainland and choose the marsh as a poetic hinterland? The answer will not be found among the 'touristed' streets that surround Saint Marcus Plaza, nor under the foundations of the palaces of the Grand Canal , no matter how old and ancient, a symbol of past glories, that shine before our eyes. Not even the flirty and very interesting San Giacometto church, next to the Rialto Bridge , can provide us with a reliable answer to the question of “why Venice is Venice” , although it is considered the oldest church in the city.

The legend tells that it was here, at the Rialto, under the stopped clock of San Giacometto, where it all began, and the hands that lost time centuries ago remind us that even time stops to admire the city of the lagoon; but it was not at Rialto that the needles of Venice began to race.

Let's stand for a moment mid-sixth century. The Western Roman Empire has fallen relatively recently (AD 476), and the Byzantine emperor's attempts Justinian of recovering Italy have given rise to a merciless war between ostrogoths and romans that will devastate the once richest province of the Empire for 20 long years in an event that will go down in history as the Gothic Wars (535-554 AD).

After years of calamity, the patrician nobles, bishops, counts and landowners chose Torcello to start a new life.

The population flees to the countryside because prices in the cities skyrocket and it is impossible to live in them due to famine and plague which, arriving from Constantinople (where it had ended up with 40% of the population), wreaks havoc on the battered Italian territory.

Thousands of small civitates and municipalities are depopulating while the powerful lock themselves in their towers and turn their backs on the world, clinging to their treasures. Only Ravenna, hidden among the reedbeds of the Po, strives to maintain the brightness of a Roman past that is fading hopelessly.

In the midst of this chaos, the news of the ruin of Italy crossed the Alps, and reached the ears of a people who inhabited the lost borders of the Empire in what is now Austria and who professed an Arian Christianity condemned from the first councils of the Church: the lombards . In the year 568, with the peninsula submerged in the postwar period, 5,000 Lombards along with their families and personal belongings cross the Julian Alps and enter Italy sowing chaos and destruction.

A new climatic phenomenon led to the abandonment of Torcello

Analogies are not well received when talking about History, but here I will resort to them in order for the reader to understand (to understand, it is best to resort to the excellent Venice. City of Fortune, by Roger Crowley) the trauma that the arrival of the Lombards meant for Italy and its inhabitants, who were not only barbarians, but something much worse: heretics.

Let us imagine that Barcelona, Tarragona, Valencia, Alicante and Murcia were devastated and depopulated overnight by a horde of savages that rode without brake through the AP-7, as happened then with the wealthy cities of Aquileia (fourth in population in the Empire), Padua, Verona, and Milan , located along the wide Roman road that led to the Danube.

There was no force to stop this invasion: the Byzantines, outmatched on all fronts, took refuge in the fortresses of the Apennines and the marshes of Ravenna to observe from afar how the Po plain, the most fertile cereal area in Europe, was taken by that indomitable people. Veneto, the mainland of an unborn Venice, was the hardest hit region, as it was also the richest and had the most populous cities.

Without Byzantine help and seeing how the Lombards imposed their Germanic laws, so repudiated by the Romans, many Veneti began to think of escaping. The question was where, and the answer came thanks to something that may sound familiar to us: a phenomenon linked to climate change.

Basilicas of Santa Maria Assunta and Santa Fosca

As if war, plague, famine, and the Lombard invasion hadn't hurt enough the population of the ancient Roman province of Venetia et Istria during the period from 533 to 570, In the year 589, a phenomenon known as rotta della Cucca took place, recorded by the Lombard historian Paulo Diácono as "a deluge such as had not been seen since the time of Noah".

The Romans were aware of the seasonal nature of Mediterranean rivers, and their engineers cleaned the channels and built dams to prevent flash floods caused by cold drops. This has been done for centuries, but With the fall of the Western Empire, these maintenance tasks were forgotten at the worst possible time.

The cold climate that characterized the Roman period worsened in the 6th century and, after weeks of endless rain, the Adige and Brenta rivers, wide and mighty, overflowed and devastated the Venetian plain transporting tons of sediment towards the Venetian lagoon, changing the course of hundreds of tributaries and the physiognomy of the marsh. Once-sunken lands emerged and wide channels were formed that allowed navigation.

The Veneti, their land devastated by water, war, and disease, and their bishops offended by the heresy of the Lombards, they thought that this succession of calamities within 50 years could only be a divine punishment, and they launched themselves out to sea, looking for a new beginning.

Interior of the Church of Santa Fosca

Some found shelter in Rialto, on the banks of the Grand Canal excavated by the flood , but it was only a tiny community of fishermen. **The patrician nobles, bishops, counts and landowners who once populated the mainland found accommodation in Torcello, and there, sheltered from the Byzantine naval force, they decided to turn their backs on the mainland.

This is how the story of Venice begins,** with an amalgamation of stories of refugees, emigrants, natural disasters and the search for a better home; a speech that, after 15 centuries, does not stop sounding certainly current.

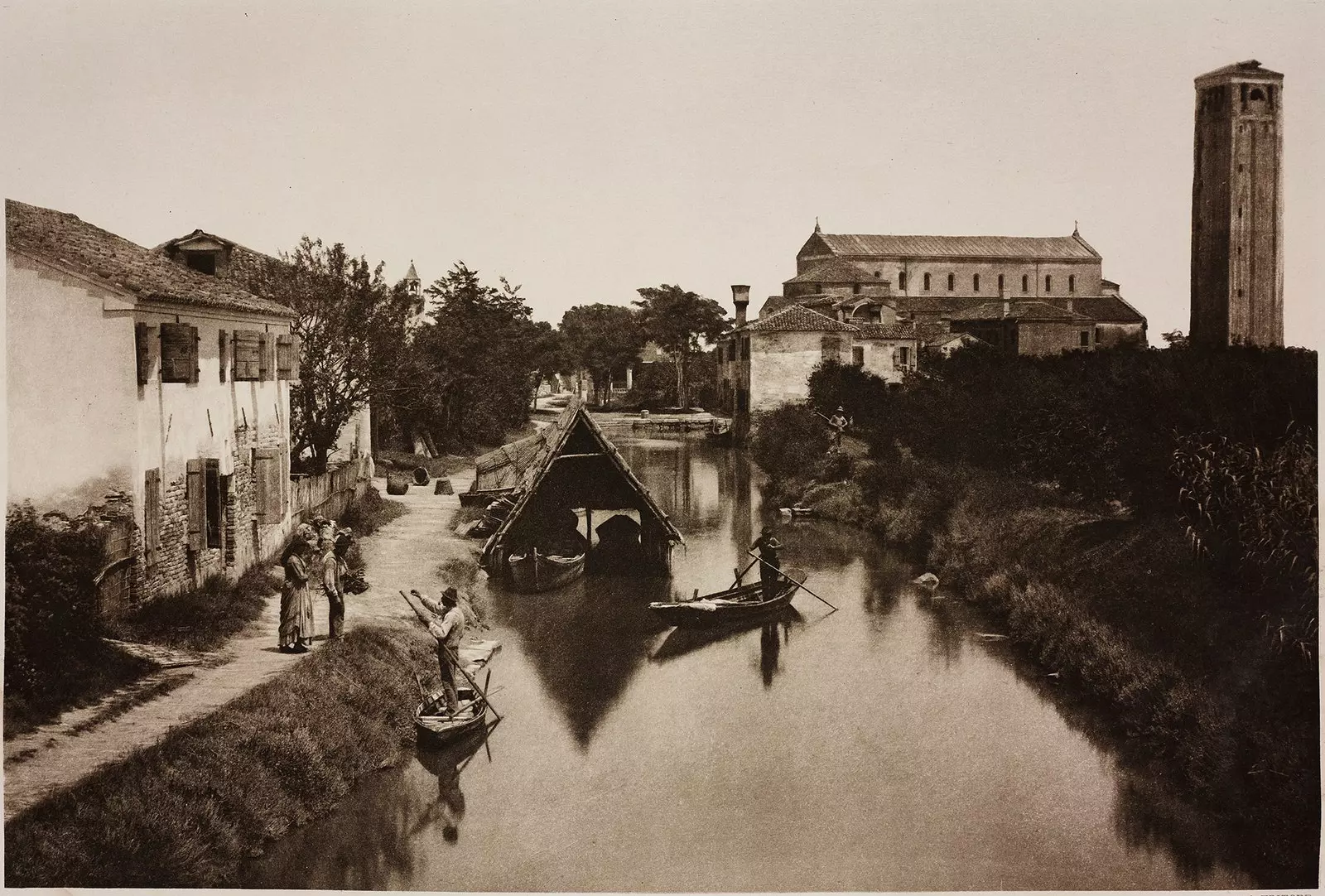

Remnants of these beginnings can be found three quarters of an hour by vaporetto from the Fondamente Nuove, in the island of Torcello, which came to house more than 10,000 inhabitants and was a whole city when Venice was just a town of stilt houses. It was here, where no one lives anymore, that the first Venetians settled.

The journey to Torcello provides a different, distant view of the well-known city, and also allows the visitor to get to know Murano and Burano, charming miniatures of Venice, towards whom their roofs and bell towers turn. Torcello, on the other hand, rests forgotten on the reedbeds, and we do not guess its existence until we distinguish the towering bell tower of the Basilica of Santa María Assunta standing out in the distance.

The vaporetto leaves us next to a narrow canal that leads to a monumental square where silence reigns and a stone throne that, according to legend, once housed Attila's butt. In front of the seat stand the basilicas of Santa María Assunta and Santa Fosca, banners of a Byzantine art that we will not find north of Torcello.

The interior of Santa María Assunta shines with the gold of some mosaics that testify the wealth of the city during the High Middle Ages, when it was the 'gate of the East' and all the spices, silks and products from Constantinople arrived here. The Adriatic served as a highway of artistic, religious, philosophical and political influences, connecting Greece with Northern Europe through the ports of the Venetian lagoon.

Such was his fortune, the island on which Torcello was based could not support more population and the inhabitants began to move to Rialto, Murano and Burano , thus beginning the importance of Venice when the new inhabitants met around the primitive ducal palace . The rest is no longer origin, but the very history of the Serenissima: Torcello is just a beautiful prologue that is worth visiting.

A new change in the climate triggered the decline of Torcello, whose history, like a fish that bites its tail, is sentenced by a new phenomenon. The medieval climatic optician unusually raised European temperatures between the 9th and 14th centuries, causing the once safe marshland that surrounds Torcello to become a breeding ground for malaria and diseases that did not invite people to continue living in it. The fields and canals were abandoned, and lack of maintenance caused siltation that made them impassable.

Through the streets of Torcello

The city built in marble only continued to house his diocese as an exercise in melancholy and served as a quarry to build the palaces of Venice, where the population of the city emigrated. Only the basilicas remained standing, as a link between Venice and its origins.

The loop is joined by ascending to the top of the bell tower of Santa María Assunta, a must-see for the traveller, and contemplating to the north the snowy peaks of the Alps, through which the barbarians arrived, and the distant rooftops of Venice, where those who found refuge found refuge. they ran away from them. And in the middle, Torcello, lost and silent mystic, bridge between the land and the sea, now enveloped in a deep lethargy.

Not even the footsteps of the tourists will manage to wake her up: we will have to wait for a new climate change so that, awake, she opens her eyes.

The loop is joined by ascending to the top of the bell tower of Santa María Assunta and contemplating the snow-capped peaks of the Alps to the north