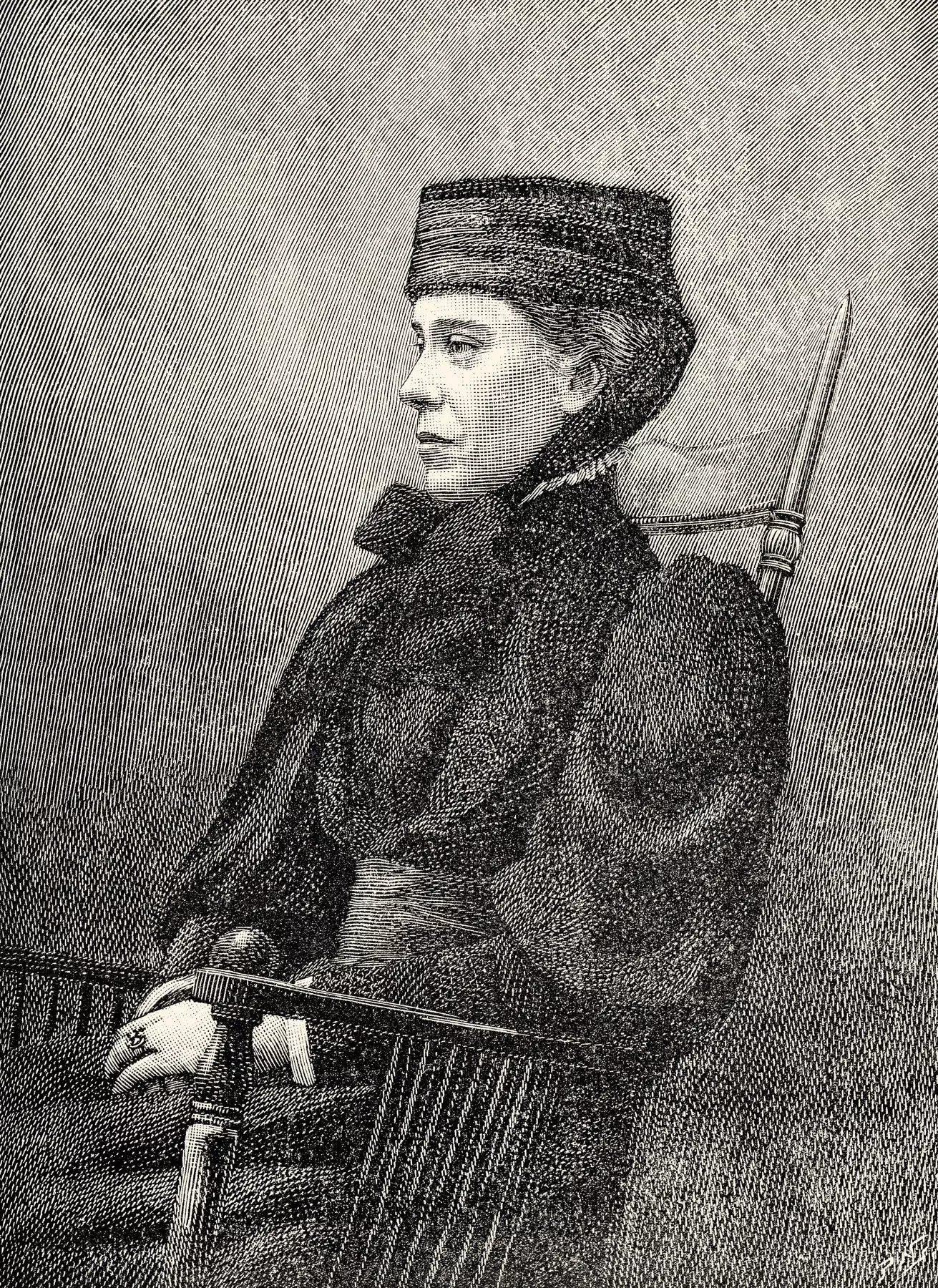

Mary Kingsley: the great explorer of Africa

Said Virginia Woolf that to be a writer she needed a room of her own and 500 pounds a year. Literature allowed anonymity, but the trip implied a physical affirmation in an exclusively male world. If the objective was scientific, to the material and social obstacles were added the lack of formal education in front of her colleagues.

Mary Kingsley was born in 1862 in London. Her father was a doctor known for his traveling therapies. As part of her prescribed treatments, she traveled with her patients to Spain, the Pacific, and accompanied Custer on the expedition against the Sioux she based on They Died With Their Boots On. Your travel chronicle South Sea Bubbles achieved great publishing success.

Mary grew up surrounded by stories, but Victorian morality stated that a young woman from her environment did not require formal studies. Her restlessness made up for the lack of secondary education with the extensive historical and geographical documentation housed in her family library.

Mary Kingsley always maintained a poetic vision of what surrounded her

When she reached maturity, Ella Kingsley couldn't help but wonder the reason for the difference between the education of her brother, who studied law at Cambridge, and his, that she limited herself to learning German and nursing courses that she abandoned when her mother fell ill.

Fortunately, the care that she was supposed to provide as an unmarried daughter did not last. Her parents died before she was thirty years old. The considerable amount provided by her inheritance allowed him to fulfill the traveling dream that her filial duties had prevented him from doing.

"For the first time in my life I found myself in possession of five or six months that were not determined by others and, feeling like a child with half a crown, I rambled on what to do with them," she wrote.

Her imaginary had taken shape in the chronicles of the explorers of the African continent: Burton, Speke, De Brazza. But in 1893 it was puzzling for a woman to travel alone to black Africa. Mary ignored the warnings.

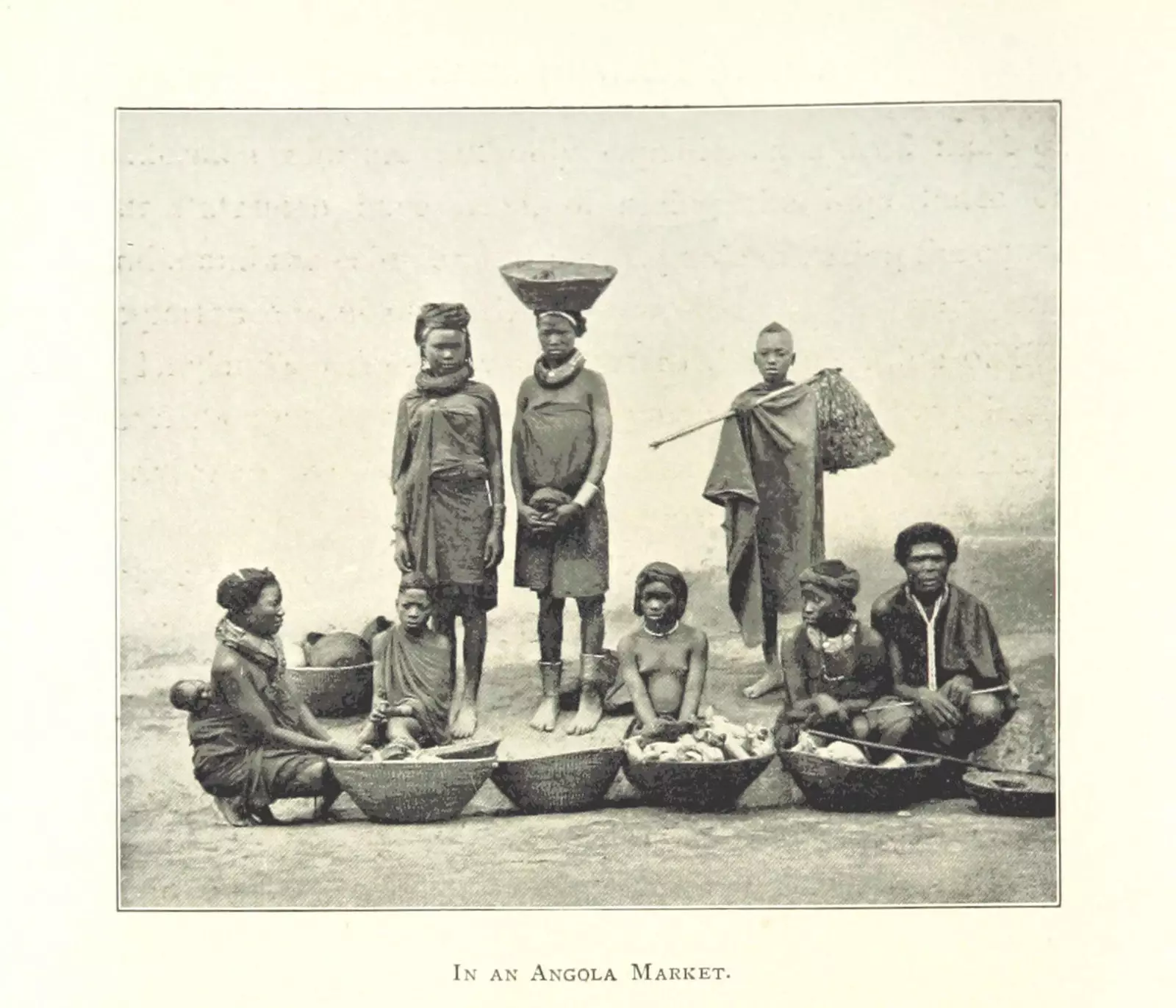

Image from Kingsley's book, West African Studies

EXCESS BAGGAGE

On her first trip she over-equipped herself: a waterproof fabric sack with sheets, leather boots, a revolver, a knife; photographic material; clothes like the one she wore in London; a personal and a scientific diary; jars of formaldehyde to conserve native species.

She embarked in Liverpool on a merchant ship heading to Sierra Leone. There were only two other women on board, and both left the boat in the Canary Islands.

"On my first trip, I did not know the coast, and the coast did not know me. We terrified each other." Arriving in Freetown, she felt embarrassed by the human and animal traffic in the streets, by the confusion of the market, by the noise.

She stayed with a British commercial agent and, when she got over the first shock, she undertook the exploration of the coast of the Gulf of Guinea to Luanda, in Angola, and entered present-day Nigeria.

West African Studies

She was traveling alone, with the help of native guides and porters. Her goal was to investigate the customs of the local people. She was aware of her gaps in ethnographic matters and, therefore, she did not consider herself an anthropologist.

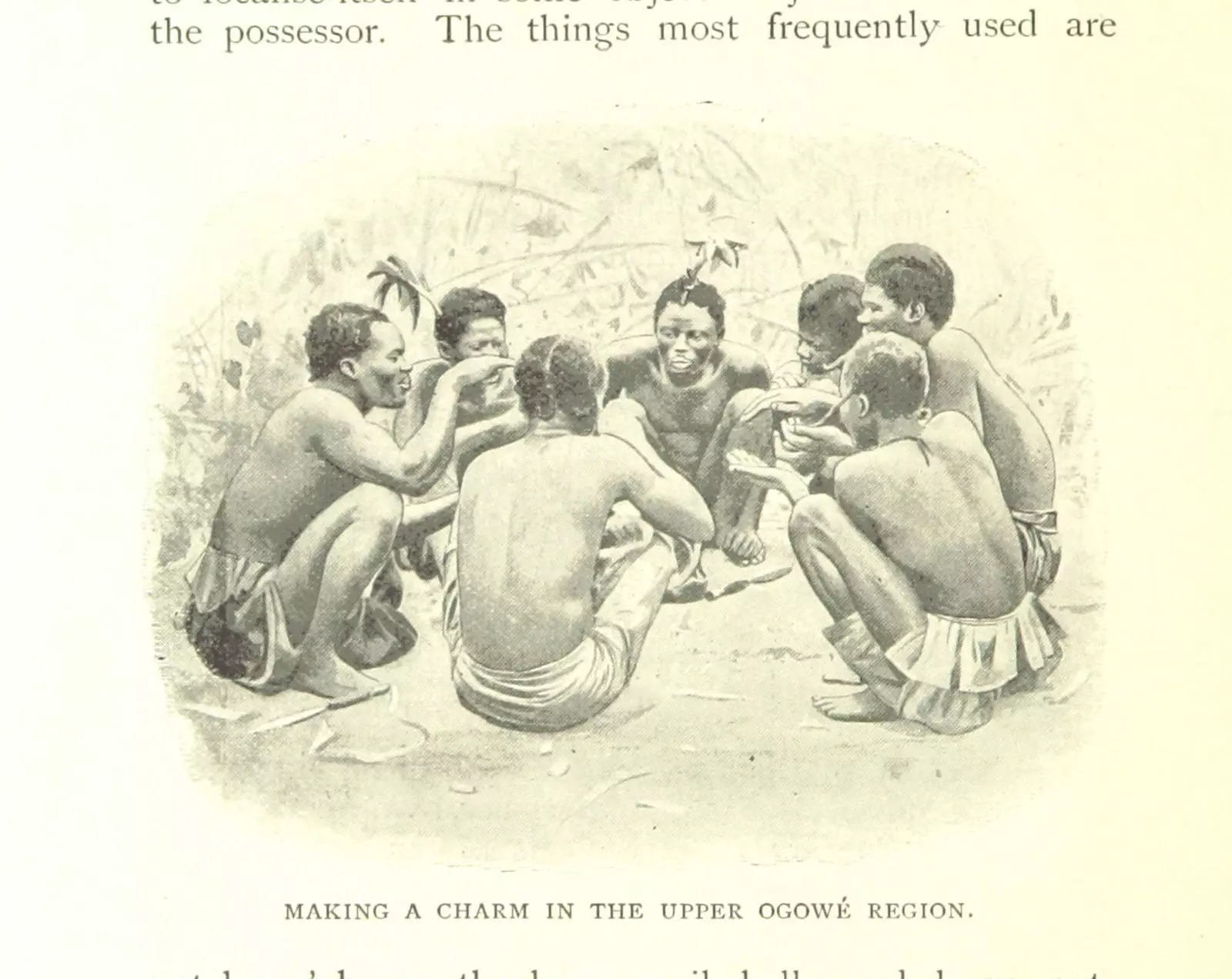

Her referents were Burton the explorer, and the writings of Edward Burnett Tylor. This considered the animistic beliefs of the indigenous people as a way of understanding the environment alternative to science and reason.

Kingsley approached her scientific work from the participant observation , which required coexistence with the tribes she studied. She was one of the first ethnographers to carry out real fieldwork and a forerunner of cultural anthropology.

Life in the thicket caused, among other episodes, a confrontation with a leopard that she hit with a water jug and a constant fight against insects.

“One of the worst things to do in West Africa is to acknowledge the existence of an insect. If you see something that looks like a flying locust, it is better not to pay any attention to it; remain calm and trust that it will disappear. There is no chance of victory in close combat.”

Mary Kingsley (1862-1900)

FISH AND CANNIBALS

The return to England was aimed at obtain financing for her next trip. She drafted a manuscript from her diaries which she submitted to Macmillan, her publisher, and delivered the fish preserved in formalin jars to Günther, in charge of the zoology area at the British Museum.

He showed interest in the area between the Congo and Niger rivers, still unexplored. The ethnographer and explorer added to these supports to Sir George Goldie, Director of the Royal Niger Company, defending British interests in the region.

In December 1894 Mary embarked with Lady Macdonald, the wife of the governor of the Protectorate of Niger, which included the south of present-day Nigeria.

Equipped by Günther for collecting fish, Kingsley aimed investigate the cannibal tribes that inhabited Gabon, then part of the French Congo.

Relying on trade missions and agencies, she went up the fluvial courses in expeditions that she reflected in lyrical key in her diaries.

“The great river oscillates around a path marked in silver. On the sides rises the darkness of the mangrove walls and, above it, the vegetation embraces a strip of stars.”

Despite the hardship of the journey, her gaze moved away from that of her contemporary, Joseph Conrad, who, in Heart of Darkness, poured out the terror that the interior of the black continent inspired in him. Kingsley maintained the poetic vision that allowed him the closeness to the tribes and the ability to observe and understand them.

In the first incursion she reached as far as the Calabar region. There she met Mary Slessor, a missionary who had single-handedly taken on local customs. She welcomed women who, having given birth to twins, were killed along with their children because they believed they had lain with an evil spirit. With her, Mary battled a typhus epidemic.

Mary Slessor with some adopted children

On the next expedition she went up the Ogooué river. From the Talalouga mission she undertook a journey that took her through swamps and uncharted areas of tropical forest to reach the Fang, a supposedly cannibalistic people.

She reduced her luggage to a tea bag, her scientific kit, a comb, and a toothbrush. She traveled on foot and by canoe, which she learned to pilot and whose comfort she extolled in her writings.

“When the external circumstances are reasonable, there is no form of navigation that is so pleasant. The swift, gliding motion of a well-balanced canoe is more than just comfort, it's pleasure.”

Along the way she encountered elephants, crocodiles, gorillas, hippos, and monstrous leeches. After traversing the Fang territory, whose customs she studied, she scaled the 4,000 meter Mount Cameroon.

She returned to England with hundreds of pages of ethnographic notes, 65 unknown species of fish and 18 of reptiles.

ASSAULT ON THE COLONIAL ORDER

Kingsley's return marked the beginning of the controversy. From the position she provided her notoriety as an explorer she attacked the Eurocentric view of Africa. She denied the superiority of the white man and she defended the cultural difference against the generally accepted racial difference.

She criticized the acculturation carried out by both the missionaries and the colonial authorities, as well as the lack of information in the press regarding African affairs.

Her spearhead was polygamy, which she claimed as a legitimate trait of the local tribes. She did not get involved in the feminist movement. Her battle had only one goal: the protection of West African cultures.

Nonetheless she was aware of her vulnerability as a woman and a scientist. She was attacked for assuming a masculine attitude in her investigations of the Fang. She denied the accusation that she had worn pants on her expeditions, and when her editor commented that her style in West African Travels was not feminine, she was offended.

When the Boer War broke out she volunteered as a nurse. She died of typhoid fever in present-day South Africa at the age of thirty-eight. The serenity and empathy that her writings convey are still a source of travel inspiration.