If the novel Nada (1945), which catapulted Carmen Laforet as one of the most influential Spanish writers of the 20th century, takes place in her native Barcelona, Gran Canaria symbolizes the childhood and adolescence that the author treasured with suspicion throughout her life. Through her novels and her travel books, the rugged landscapes and the busy ports of this land , so attractive to her protagonists as unknown, and that she ended up rising as one more character in her literature.

The real and fictional scenes that Nadal award winner constantly recounted in her work because of her geography are infinite, like that dip that she enjoyed before lunchtime on the urban beach of Las Canteras, in her words, “a lonely beach then in winter, even though there is no winter in the Canary Islands”.

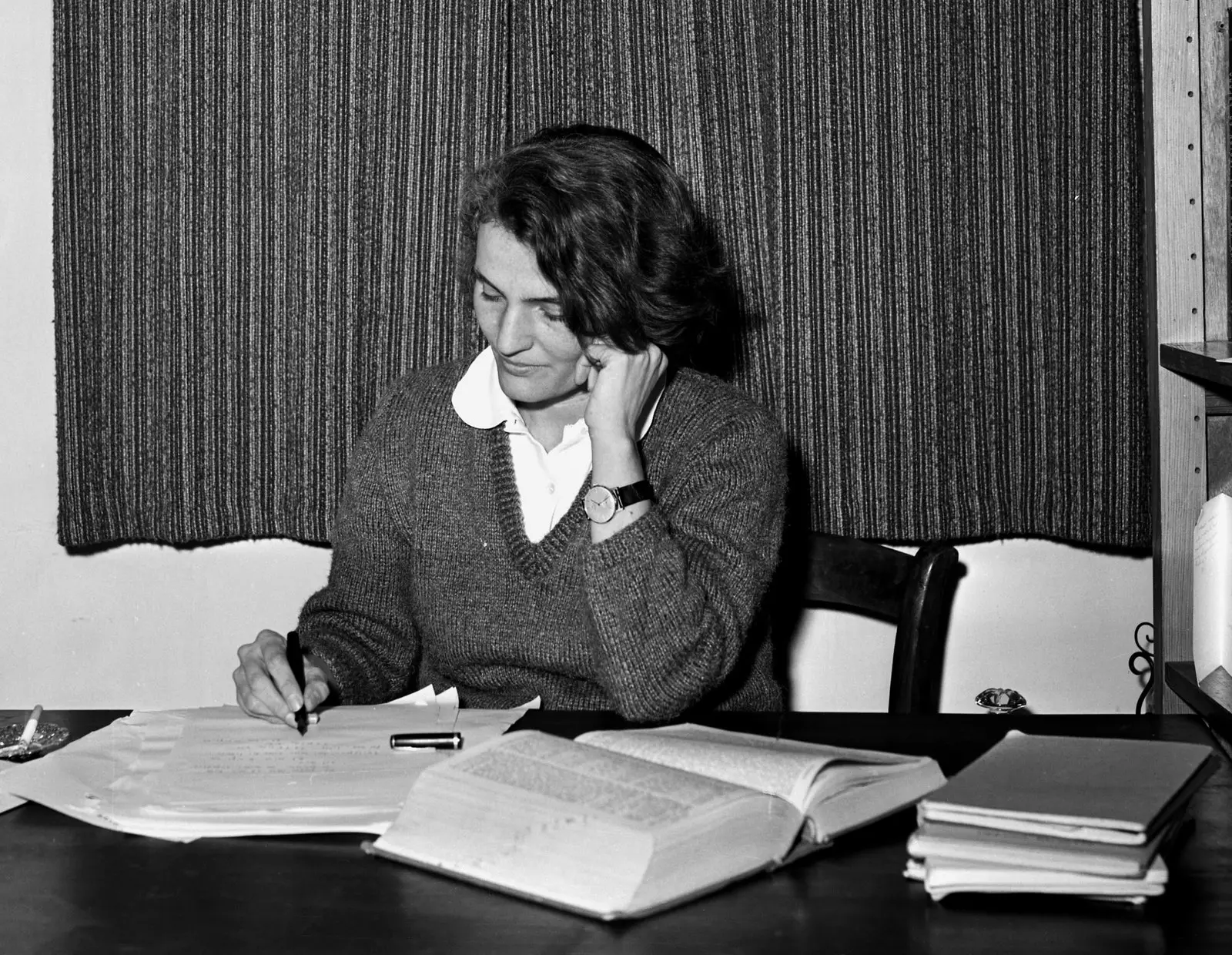

Carmen Laforet in 1962

When she came of age, she returned to the peninsula to study Philosophy, leaving behind Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, that city where her father, the architect Eduardo Laforet Altolaguirre, modernized with a new Canarian style and regionalist buildings –the disappeared Avenida cinema or the headquarters of the Cabildo de Gran Canaria, renovated in 1942, promoters of the culture and heritage of the island, were some–. But luckily the stylized and almost mystical vision that she composed in her youth of this island in Northwest Africa is still trapped in her novels, and becomes the best compass to explore it.

With the northeast as a starting point and after leaving the capital and Laja beach , whose black lava sand witnessed Laforet's childhood – “in which she stuck her nose to the surface of the water to glimpse the mysterious life of aquatic plants” as she narrated in a chronicle–, the Ascent through the GC-802 region offers a landscape just as laforetian, the Bandama Caldera.

Sculptures and painted houses in Agüimes.

This volcanic gorge that takes your breath away with its basin three kilometers in diameter , is one of the largest depressions in the archipelago and where the action of your novel takes place The Island and the Demons (1952). Escorted by the Pico de Bandama, discovered by a Flemish merchant who planted vineyards on his land back in the 16th century, contains the Monte Lentiscal, where Laforet's father built luxurious residences.

Along its primitive stone paths, you can approach the false crater until you reach the top and see its forests at almost 600 meters above sea level. East rough and wild landscape, of nature without artifice , also persists in the Barranco de las Vacas, on the road that connects Temisas with Agüimes.

Inside, prehistoric waters shaped the geological canyon known as colored tuffs, that shares that reddish rock face of the cinematographic Antelope Canyon in the United States. The difficulty in locating it (Google can play tricks on us if we do not enter the exact coordinates) does not prevent it from being a great attraction for influencers from all over the world, who yearn for the perfect selfie on the rock that crosses the gorge. Enjoying it alone is practically impossible, but more feasible during the week if you visit it first thing in the morning.

Cow Ravine.

On the way down, the town of Agüimes, with its murals and narrow streets of exposed stone houses and cheerful colors, where time (and the winds that embrace the mountain of the same name) seem to stand still. With a historic center dotted with hermitages, sculptures of princesses and writers and inns where to catch up with its immortal vegetable stews, the Plaza del Rosario concentrates the daily hustle and bustle.

Here they alternate cafes like Populacho (Pl. del Rosario, 17), that has been animating the town since the nineties with long after-meals that take place on its turquoise bar of infinite liquors. The parish church of San Sebastian , solemn and neoclassical, dominates the city in height with a floor of dark stone reminiscent of the volcanic remains and the sand of its ancient beaches.

Populacho Cafe in Agüimes.

After taking an artisanal bread as a souvenir (they say it's the best on the island) it's time to hit the road again to cross another of the peaceful "demons" that the island offers: the Gauyadeque ravine. This deep depression between the municipalities of Agüimes and Ingenio seems to divide the island in two, entering prehistoric times when the paved road ends at the troglodyte settlement of Cueva Bermeja.

Carving out a life on the rock of the mountain in the 21st century is not science fiction, but rather the result of the isolation that the area received until modern times. With hardly any mobile data and guided by a map we start a route of about 15 kilometers only suitable for hikers in good shape (with six hours on foot and almost 1000 meters of difference in altitude) around that monumental abyss that the water dug millennia ago to its mouth on the coast. A necropolis in broad daylight where you can come across mummies and funerary caves, as well as archaeological remains and cave paintings in its museum, also deepened under the green mantle of the mountain.

Guayadeque Ravine.

At lunchtime you can decide on one of their cave-restaurants with local cuisine (El Vega, always lively and famous for its suckling pig in salt; or La Era, quieter, with few tables and views of the ravine) or do it for free in its picnic areas, under blooming almond trees if we cross it in January and February. A perfect place to gobble up that spoils that we will have accumulated in our passage through the area, such as the aforementioned artisan bread, Los Dragos cheeses, Señorío de Agüimes dry white wine or Caserío de Temisas olive oil.

When the first hour of the afternoon approaches, the same one in which the light begins to decline and merges with the mist that counts the climb to the mountain, It is the most photographic moment to set course for Tejeda. Rows of prickly pears crowded with figs (tuneras for the locals) serve as a guide to the bowels of the island, starting from this municipality inside a volcanic caldera to the Parador de Cruz de Tejeda.

Reviewed by Carmen Laforet in her travel guide Gran Canaria (1961), this hotel complex that retains part of the original structure from 1937 It is located in the summit area between cliffs and boasts of having the best panoramic view of the island. Here you can wake up with views of the Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria, an archaeological rarity that marks the winter and summer solstices through the sun's rays that pass through its natural stone windows.

Bell tower of the Cueva de Artenara hermitage.

It also does not detract from a walk through the Canarian pine forests that surround it (essential if the good weather accompanies) or recover after the route with a volcanic rock treatment or honey baths in its spa. If we took a liking to the ascent by road, for which to slow down the speed for the benefit of a landscape that is diluted with the sky, Artenara is a mandatory stop.

The highest town on the island, and also the least populated, offers from its viewpoint guarded by a bronze statue of Miguel de Unamuno a chilling vision of Roque de Bentayga. This spiritual axis of the aboriginal world in Gran Canaria, supported by prehistoric rites and legends, eclipsed the Bilbao writer who described it as "a storm of stone" during his stay on the island in 1910.

Rock of Bentaya.

Is round island with one ear cat face as some describe it, "a miniature continent" for others, hides among valleys, ravines and dense forests some jewel-towns that still resist tourist handling. It is the case of fear, an immovable stop of the route through the north of the island that Laforet traced in 1961. Basilica of the Virgen del Pino , with large windows and gargoyles that crown Calle Real de la Plaza (recognizable by the historic wooden balconies that border it) immerses this town, the fruit of religious devotion, in a mysterious setting when the fog falls.

Its square hosts on Sundays a municipal market with all kinds of handicrafts , which perpetuate the trade of the old workshops in the old town with embroidered tablecloths, baskets or works in clay and cane. The same tradition that runs through the recipes for ropa vieja and marinated meat in their food houses. And when it comes to sweetening the stomach, all you have to do is think about desserts (oh their anise and trout buns!) made by the cloistered nuns at the Cistercian Monastery since 1888.

Cheeses in the Teror market.

But if we talk about religious monumentality, Arucas takes the cake with its neo-gothic cathedral, the Iglesia Matriz de San Juan Bautista. A mass of stone covered by elegant windows made by the Maumejean family of artisans (also authors of the windows of the Hotel Palace in Madrid or La Granja) and that can be seen for miles between prominent palm trees.

This historic municipality is well worth a stroll through its streets of colorful and stately buildings (with its orange dome from 1912, the Heredad de Arucas y Firgas is one of its modernist jewels) and get lost in the Garden of the Marchioness of Arucas . What was the summer residence of the first aristocrats at the end of the 19th century is now a free passage public park, marked by paths of romantic style with botanical species brought from different parts of the world and colonies of peacocks. But its most famous building is the historic Arehucas rum factory (the distillery is accessible for visits), symbol of the flourishing that the city experienced since the fifteenth century due to the cultivation of sugar cane.

The last stage of the journey encourages you to explore the northernmost face of the island under the light of the Atlantic Ocean that Carmen Laforet described in detail in some of her novels: “The sun, on its way to the West, reddens the Atlantic behind the Summit, and is going to sink beyond the mountains of the island of Tenerife, turned into smoke by the distance” (The Island of Demons, 1952). Among the pine forests that announce your arrival in artenara the writer met galdar , a mountain fragmented in the distance by tiny colored facades as if they were a blanket of vibrant patchwork. Going through its streets implies unraveling the history of this aboriginal people, either by visiting the cave paintings of his Painted Cave or the busy Plaza de Santiago from the end of the 15th century.

Galdar.

On one of its sides is the emblematic Agáldar hotel, whose terrace with views of the mountain is a good place to plan an appetizer based on salad with octopus and local potatoes, which will later be extended in La Trastienda de Chago with wines made from Listán Negro and Tintilla grapes (such as those from Bodega San Juan) grown in Santa Brígida. From this square also arises the Causeway of Captain Quesada (known as Calle Larga) flanked by iron arches and the historic market of La Recova, which houses works by local artists.

Leaving Gran Canaria without taking a dip in that sometimes rosy sea that the writer revered so much would be an unfinished trip around the island. The natural pools of Roque Prieto, La Furnia or El Aguajero, away from beaches crowded with tourists, they are also a good place to get the pulse of the local life that northerners practice among sun baths, breakwaters and virgin altars carved into the volcanic rock. And in which to witness a sunset clinging to sparkling tones, ranging from red to violet, when the sun disappears between its ravines and mountains. So revealing and unbreakable that Carmen Laforet kept it forever in her novels.