The VDNKh complex (Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy)

we stay in 1931 , buried in a hole in the center of Moscow. A good reflection of the history of the capital, both for the swampy times in which we find ourselves and for the determination to make this place the emblem of national exploits.

Since the fourteenth century, at this same point, the Alekseevsky monastery Orthodoxy was imposed in the midst of a dispute between Russians, Lithuanians and Poles to possess the city. In 1812, Nicholas I gave the demolition permit to build the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a tribute to the victory over Napoleon. And nearly 120 years later, Stalin flies it to raise his particular tribute after defeating the bourgeoisie and religion and, by the way, give a clue as to where the shots of his legacy will go.

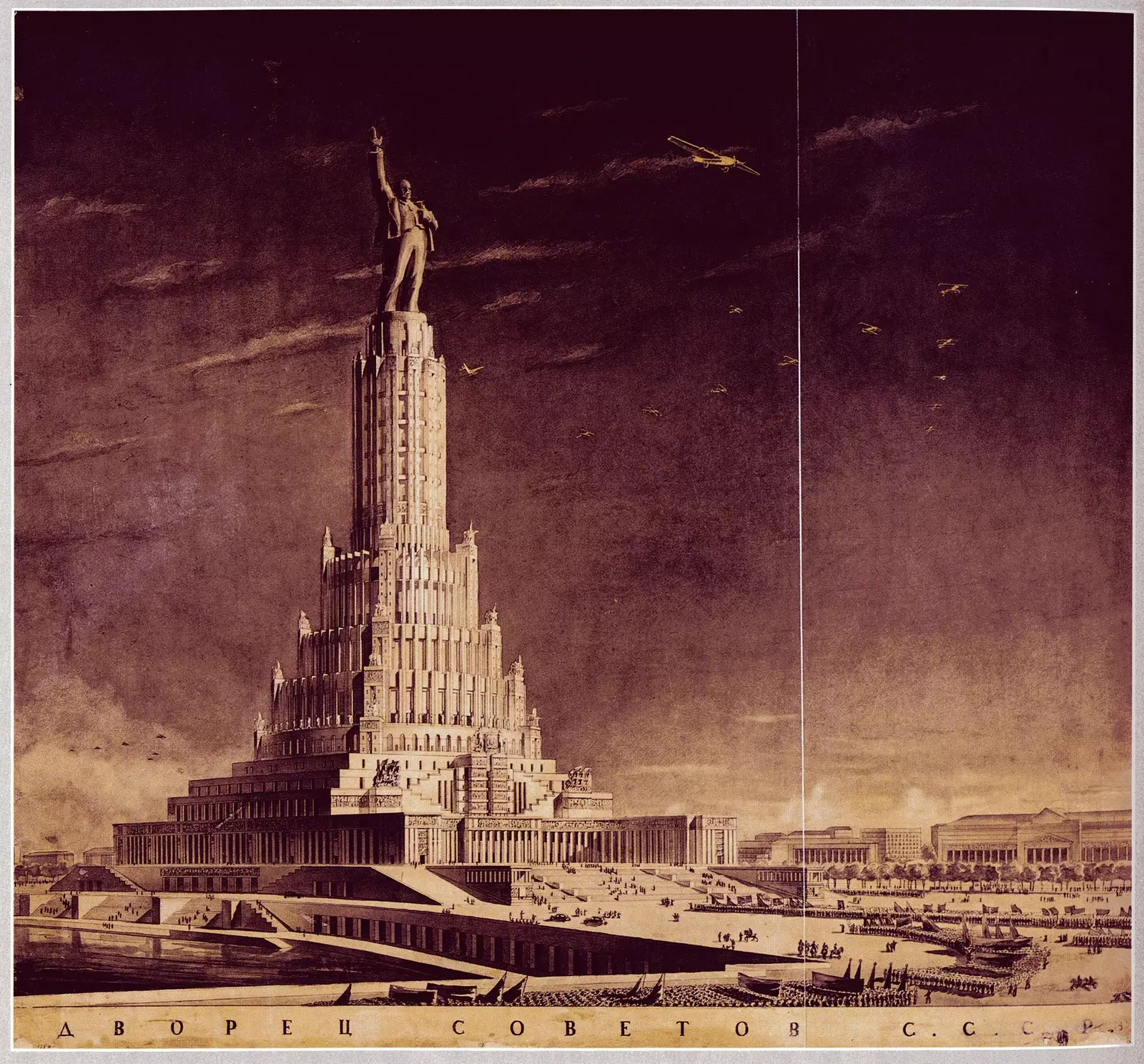

Image of what was to be the Palace of the Soviets

Hand in hand with him we meet Boris Iofan, an architect from Ukraine and educated in Italy, who would import to the Soviet Union the grandiose features of totalitarian architecture.

In fact, in front of the Cristo Salvador Cathedral itself are the well-known Housing in the Ribera, one of Iofan's first works, which anticipated the turn that avant-garde architecture would undergo in the 1920s, although they retained constructivist features. Iofan himself settled there, closely following the progress of the construction of the Palace of Soviets.

His project had prevailed over proposals from Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius or Armando Brasini (his Italian teacher), among others; the choice of its neoclassical features would mark the aesthetic line of Stalin's mandate... And the vicissitudes of its non-construction would exemplify the traumas of economic development up to the Khrushchev era.

Between flooding and flooding the hole, on the other side of the Kremlin, took shape the Hotel Moskva, one of the largest and most amorphous buildings in the capital.

The Moskva Hotel, now the Four Seasons in Moscow, is one of the largest and most amorphous buildings in the capital

The dimension does not need to be explained; on its asymmetric facade and incompatible styles, the most poetic theory is the one that points out that, in front of some plans with two different proposals, Stalin planted a signature in the middle. Terrified of asking her to specify his preferences, the architect decided to simply execute both. An anecdote that was decided not to correct when, in 2004, it was demolished to build an exact replica. Reopened in 2014 as Four Seasons (yes, with different services).

Now 1938 . The flooding of the hole continues, but the Palace of the Soviets manages to take height, just as the city begins to portray another of the clear features of Stalinist architecture: imperial-style urban planning, that reaffirms the concentric structure of the city and connects it through large radial avenues.

Just like in St. Petersburg, the banks of the rivers are formed as the reference location, and new housing projects recover single family apartments, after the experience of the comunalcas. Also, the population density of each street is limited and the reference heights of the buildings on the main avenues are set (except in St. Petersburg, which still respects its original size today).

These urban developments are implemented in Moscow from the very beginning. As highlighted by the urban planning expert Deyan Sudjic, "With the Kremlin at its heart, the city retains a structure bequeathed by the medieval autocracy. Since 1917, it was the object of the effort to make it the capital not only from Russia or the Soviet Union, but of a new world order. A capital formed not by the market, but by an idea of what a city could be."

Kosygin State University

This development left in numerous avenues a large superposition of styles: from Iofan's classicism to late appearances of constructivism, such as the Kosygin State University, or unexpected details of art deco, such as on Pokrovskii Boulevard, in the vicinity of the Patriarch's Ponds or on the Frunzenskaya Riverside. Below all of them, the Moscow metro begins to forge its legend, that well deserves another report in the margin.

Years later, the plans of Moscow would be transferred, to a greater or lesser extent, to other capitals of the eastern bloc during the reconstruction work after World War II. Thus, the also concentric Sofia replicates in the Serdika square the style of central Moscow. This same Stalinist imperialism (or socialist realism) gives all its monumentality to the center of Kyiv , with Khreshchatyk avenue and surroundings. The same is true of other cities most affected by the conflict: Minsk, West Berlin or Volgograd (then Stalingrad).

If the war changed the morphology of these cities, Moscow too was forced to rethink itself. Despite the insistence on going ahead with the Palace of the Soviets, whose structure in 1941 already reached 11 of its 100 stories high, reality ate dreams. All this iron frame was dismantled and used for war material. From his window in the Riverside Homes, the architect Iofan saw how the hole returned to its flooded origins.

Serdika Square in Sofia replicates the style of central Moscow

After the war, the Soviet command changed its mind and decided to use the same guidelines as Iofan himself to surround the Moscow center with seven towers that today remain the icons of the city. In a style that oscillates between Gothic and Baroque and with modernist details, between 1947 and 1953 these seven colossi were built on the seven hills of Moscow: among them, the MGU University, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Kotelnicheskaya houses or the Ukraine Hotel they are the most persecuted by the cameras.

Just as urban planning was transplanted to other cities, imitations of the "seven towers" (as they are known in Russian, as opposed to the more market-oriented "Seven Sisters" in English) they arrived in Warsaw or Riga. Its monumentality would also be replicated in the Samara opera house or the port of Sochi. And it is on the shores of the Black Sea that we find the gold medal with the Orkhonikidze Sanatorium for miners: a 16-hectare complex of gardens, fountains and up to ten modules connected to the beach by a funicular. The peculiarity is that even though the buildings are abandoned, it is still used as a public park, in which to recreate the glory and decadence of an empire not far away.

The seven towers today remain as an icon of the city

Orjonikidze continues to be the latest evolution of other works that underpin the heritage of Stalinist architecture in Moscow, such as the Red Army Theater (1929) or the Gorky Park Victory Arch (1955). Of them, the VDNKh complex (Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy) culminates the most delirious expression of this era: a kind of Soviet Universal Expo, in which pavilions from each member republic of the USSR gather around a large square, which mixes modernist and rococo. The feeling of pastiche increases with the renovation of 2014, after decades of neglect. In any case, it is an essential visit, as an ode to Soviet paraphernalia and as a reflection of the attempts to respect the particularities of each territory...

But to the point. What happened to Borís Iofan and the hole? For a few decades they stared at each other, expectantly. To try to recover the project from him, Iofan is credited with an extensive correspondence with Stalin. This made him draw other things, but he would never reach the relevance of the Palace of the Soviets or of his work for the 1937 Paris Expo, which would become a symbol of the Mosfilm film studios and of the entire city: the sculpture of the Worker and the Kolkhoz Woman, that today can be found at another expo, the VDNKh, and on quite a few stamps and postcards.

So Iofan was unearthed from oblivion, but... the hole, the hole continued to ferment. With the death of Stalin in March 1953 and after the brief regency of Georgy Malenkov, came Nikita Khrushchev , whose bald head swollen hinted that he came wanting to party.

Orkhonikidze Sanatorium

That's how it went. De-Stalinization to the song, starting with the historical memory and continuing with the process of urbanization of the population. Stalinist architecture was neither efficient nor sustainable, he decided. The hole represented a vocation of unnecessary excesses. Khrushchev returned it to the people: was completely flooded to build one of the largest outdoor heated public swimming pools (yes, in the center of Moscow).

With the cities he would do more or less the same. Take advantage of the appearance of new construction materials to flood them with five-story buildings (khrushiovkas). Between 1917 and 1961, the urban population went from 17% to 50%. They would have to swim in neighborhoods more bland than the glamorous ones of past decades... until in the 1970s a new revolution perched on the stagnant Soviet landscape.

Of course, the history of the hole does not end here.

The VDNKh complex culminates the most delirious expression of this era: a kind of Soviet Universal Expo