Preparing often soup (tripe) at Barbacoa El Calandrio

In the Malinalco market there is a man who sells gold handles , he cuts them into pieces and serves them in disposable cups. I strongly suggest everyone buy it, because it's the best mango you'll taste in… a minute. The golden handle is nothing more than an ordinary mango , as good as a petacón, but never as delicious as the best of all mangoes, the manila, with its taste between sweet and acid : Here they serve it graciously crossed by a stick and sprinkled with chili pepper.

I hope you are hungry because there is also: pork brain quesadillas, belly (a savory beef broth with chunks of tripe decorated with oregano and a splash of lime juice), tacos stuffed with vinegar-cured pork feet, baskets heaped with bread, Squash Blossom Quesadillas , tomatoes from the garden, free samples of sapodilla (a fruit with reddish pulp and a flavor between nutmeg and cinnamon), unpasteurized goat cheese, tamales, enchiladas, natural orange juice and coffee beans grown and roasted by hand.

Do not be surprised if you see a man who, without getting off his horse, makes a stop to eat —of course— a taco! This character is not a hipster foodie looking for attention or the former president of a large company turned into a gaucho who worships organic vegetables. He just doesn't have a car. Without a doubt, something very different from what we are used to in big cities.

Malinalco is a small town about 100 kilometers southwest of Mexico City. , so it is incredible that its market on Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays is not considered essential. The rest of the Mexicans may not even know about it, although if you think about it carefully, they probably have their own markets of equal or greater quality.

I have come to Mexico to participate in a culinary tour, in the purest style of the Italian or French gastronomic routes , where almost from town to town you can find real delicacies. The plan was simple: get to Mexico City, meet a recommended driver, head south to the city of Morelos (famous for pork and chili and their endless permutations), then visit Puebla, where (maybe) invented the mole, and end up back in the huge capital, a city that never sleeps, in part because you never stop eating there. Before you angrily toss the magazine in a fit of jealousy, let me assure you that my purpose is much more ambitious than enjoying this gastronomy , although I can't help but delight in it. I am here to find answers to these two questions:

1. Is Mexican food in Mexico really much better than what they serve in the rest of the world?

two. And if it is, what is the reason?

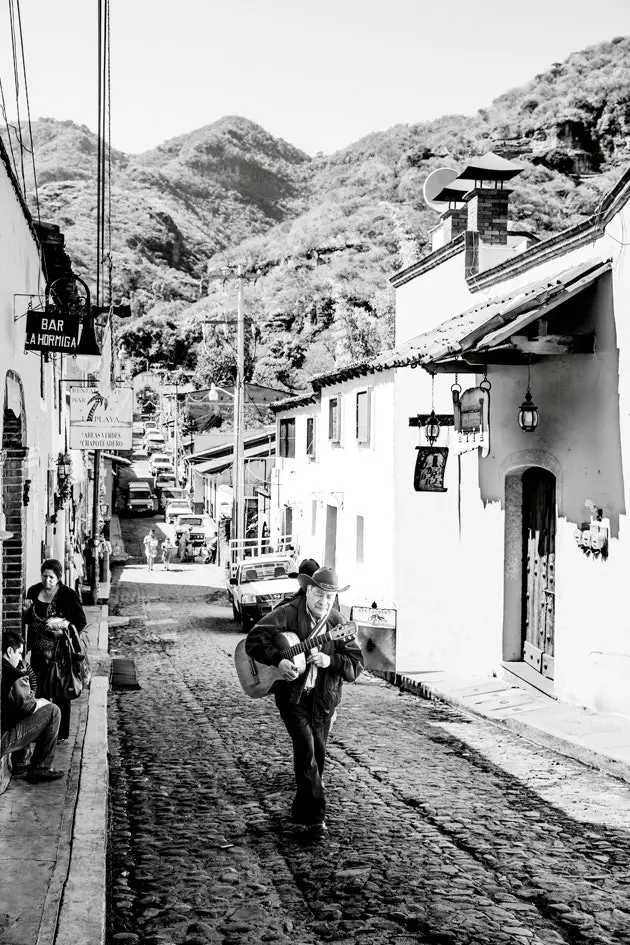

A musician goes to the Malinalco market

Before I even had time to ask the second question, I already had an answer to the first: a resounding yes! (and this was long before I met the man who sells mangoes) . Less than an hour from Mexico City's Benito Juárez International Airport, I asked my driver to pull off the road at the edge of the La Marquesa National Park , known for its towering conifers and green glades amidst forests. I wanted to visit La Marquesa, an ideal town for horseback riding . It was here that I came across a taco stand shaped like a dilapidated barn whose ramshackle stove was cooking a knuckle of pork in lard.

I decided to sit down and order something. Plastic cutlery was the first to arrive, followed by a bowl filled with chopped onions and coriander. Later, a woman served me a paper plate with two tortillas in which pieces of pork were cradled. I dressed my taco thinking it was going to be terrible and instead not only it was the best of my whole life , but it made all the ones I'd tried so far seem like a cultural atrocity. I was impressed with the delicacy of the tortilla , with the impressive flavor of the pork, with the spicy nuances of the sauce and even with the crunch of the cilantro and the onion.

This response in the form of sensation leads me to the second question, which, at least for me, is one of the most exciting of our time. A question that has been eating at me since the summer of 1996, when I spent three months as a student in Brussels, constantly amazed by the quality of their cakes, chocolates, mussels, beer, sausages and much more. Why do Belgians eat so well? I asked myself. Why the Italians? And the Japanese? And the Koreans? Why do Germans, who are more organized and wealthier than Italians, visit Italy just to eat? Shouldn't the food in Germany be better?

All this makes Mexico a very interesting place. It is much poorer than its neighbor to the north. So why is the food so good? How can any roadside taco be so much better than the most innovative and critically acclaimed taco in all of New York? (I have tried both).

It was not difficult to discover the secret: the ingredients . The corn in the tortilla was local. The chiles for the green and red sauces were collected from an orchard less than 15 meters away. Just like coriander. The pig did not spend its days inside a metal cage eating industrial feed, rather it walked through a neighbor's field, in addition to not having been cooked in pseudo-artificial corn oil, but macerated for hours in lard.

Mexican garlic and local products from the Mercado de Atlixco

He had solved the mess. Mexico, whose geography includes tropical beaches, forests, deserts, fertile valleys and snow-capped mountains, is home to a huge variety of ingredients . Although its economy is in good shape, it is far from being at the top of the agricultural industry. It's just the land of cool.

The ingredients theory was working perfectly. Each stall she visited confirmed her even more. All except the post jerky, which brought my theory crashing down . Cecina is beef tenderloin cut into huge fillets that are then salted, dried and folded like sheets. When you ask for a portion, it is when they unfold it, roast it over wood embers and serve it on a tortilla. I was halfway through my second taco when the vendor asked me if he had been to Atlixco , a town a few hours from Malinalco that I had never heard of and which just so happens to be famous for its cecina.

Not only did this cured meat threaten my theory, but other unknowns presented themselves. For example, if the secret of Mexican cuisine lies in the fact that it is a tropical country with little industrialization, then, Shouldn't Guatemala or Panama, which are more tropical and with less industry, if possible, have better food? (They do not have it) . No, he was sure it had to be something else. It was then, raising my head from the plate and looking around, that I had a revelation: are the grandmothers.

Cecina Taco at the Atlixco Market

The positions are not at all 'corporate', despite this there is a fierce competition that would excite an economics student. If you ask one of the grandmothers for any of the other enchilada stands you will find 'that look , the same as if you mention the tlacoyos (oval tortillas on which a large quantity of ingredients is placed) from another town, or the cecina of Atlixco Although it is very famous, it could never be as good as the one in Malinalco.

The only other country with the same level of culinary egocentrism based on regionalisms and where a grandmother would speak badly or with indifference about the kitchen of the grandmother across the street, even though they have known each other all their lives. That country is Italy.

We could define it as the peasant culinary theory of good food . According to this view, 'deliciousness' is not just the work of innovative chefs and their magical techniques. Rather rest in the throng of cooks and diners who not only inhabit or visit the countryside, but what 'are' of field . This theory explains why those who visit Italy come back euphorically telling about the plate of orechiettes prepared by a nonna with a wrinkled face. And it also explains why I ate so much better—and in just an hour—at a small-town Mexican market than I had during the previous three months in the so-called land of plenty.

The Italians monopolize this theory right now, but they were not the ones who invented it. He was the legendary chef Georges-Auguste Escoffier , the inventor of modern cuisine as we know it today, who made a big business by reviving the Provençal dishes of his youth and serving them to lovers of luxury. A great example of his is his Carré d’agneau mistral, a south-western French lamb dish, with artichokes and potatoes, cooked in olive oil and garlic and which he refined using butter and truffles.

The crux of the matter lies in the connection between the exclusive and the traditional , a union that can be witnessed in the mornings , a resort two hours drive east of Malinalco, in the Sierra Madre.

Tortilla soup at Las Mañanitas

Unlike others, Las Mañanitas is located right in the middle of a city, Cuernavaca . Even so, it is a green space that is not at all urban, with tropical birds and a pool that is filled with water from an artificial waterfall. Its menu offers gracefully anachronistic dishes , like lamb with mint jelly. But these are the exception in a list that includes, among other dishes, tortilla soup, bone marrow taco, pork knuckle, liver and onions and brains in a dark butter sauce. Like Escoffier, Las Mañanitas replace lard with butter (personally, I'm not convinced) , still the traditional feeling is much stronger than the refined air. When I asked for the best dish of the day, they told me escamoles (ant larvae) and maguey worms . You don't hear that every day.

If you explore Cuernavaca you will find the house of the famous Mexican comedian Cantinflas, converted into the currently closed Gaia restaurant . There you could sit on the second floor enjoying the pool with mosaics by the artist Diego Rivera. Today, you can do it at Gaia BISTRÓ and Glu, from the same group. The great secret of their menu is the chicharrón (pork rind) soup, which with its recovery I am sure will mark a new milestone in Mexican cuisine.

I was still pending the little affair of the cecina de Atlixco , two hours east of Cuernavaca, so I decided not to linger and go for a pre-dinner slice. I have to say that the smart thing to do would have been to spend the night at **Hacienda San Gabriel de las Palmas**, a historic sugar plantation owned by Hernán Cortés in 1529 and now reborn as a resort. This way it would have been easier to get to the market at lunchtime.

Hacienda San Gabriel de las Palmas

The Atlixco market did not look messy . It is a permanent market, a lively place to find bubbly liquids, rare animal parts and lots of haggling. The tables were heaped with goat and sheep guts and pork knuckles and liver. There were giant bags of lard, dried shrimp, and jars of huitlacoche mushrooms (a delicatessen that is compared to truffles but that does not taste the same at all). A woman mixed with something similar to an oar the pork rinds that were cooked in a large pot. And there were buckets and buckets full of mole.

The jerky vendors located me before I located them. The most modest were in charge of giving free trials to attract customers. I was offered bits and pieces of this unusually tasty meat. I asked the reason for such courtesy to one of the vendors and she clarified that if the cattle are not at least ten years old and are not fed with grass and alfalfa, the taste is not the same (she enlightened me while unmasking other vendors ) .

Atlixco It is located half an hour from the city of Puebla. the poblanos they refer to it as the second city of Mexico, culturally speaking, because in terms of population it is not. It doesn't even cross their minds to make a trip to Atlixco to try cecina, the truth is that if you think about it, there are plenty of gastronomic options. It is said that Puebla is the place where the mole was born (it is also said of Oaxaca and Tlaxcala, but now listen to me).

If you don't know what mole is, it is often described as the material expression of the Mexican spirit , his intense human passions distilled into a divine sauce. It is also a tasty mixture that, although not always, has chilies.

There are hundreds of moles in Mexico, but the poblano is the most famous. You can buy it in barrels in Atlixco, although recommended, many chefs prefer to make it themselves. One of them, Gabriel Rojas he is so proud of his award winning mole poblano (yes, there are prizes) that he performs demonstrations —like the one I was lucky enough to attend— in Casareyna , a restaurant and boutique hotel in the center of Puebla.

Rojas stood up in front of a table covered with a linen tablecloth and seventeen ingredients perfectly distributed in small bowls (sesame, anise, toasted tortillas, stale bread, raisins, chocolate, cloves, lard, chicken broth, dried chilies, etc. .) . He showed this and that and then put it all in a blender. “ Special attention must be paid to the ingredients and, even more, to the process. There are too many lazy people in the kitchen." he commented. Then he melted the butter in a pan, added the mixture, and cooked it for twenty minutes. “Never add water” he warned. Then he started pouring chicken broth in little spoonfuls, as if he were making a risotto. Finally, some sugar, “to bring out the flavor of the chocolate”. Then he let it simmer for another hour.

I tried it with chicken and it tasted between sweet, spicy and salty, a chorus of flavors in which it was impossible to identify an individual note. I was grateful that Rojas hadn't been lazy about this.

Ingredients to prepare the mole poblano

According to legend, the mole was created by a group of nuns who panicked when they learned that the archbishop or viceroy of New Spain (no one knows for sure) was going to show up for dinner unexpectedly. The kitchen of these nuns —in the convent of Santa Rosa , which dates back to 1600 and is located in the colonial old town of Puebla—has been preserved as a museum where you can see a giant ancient oven , as well as clay pots and wooden spoons of enormous size.

It may be that the one about the nuns is nothing more than an urban legend, because the truth is that many things in Mexico have pre-Hispanic roots . In fact, in this dish you can perceive a often imperceptible indigenous reminiscence , the same one that is more plausibly found in most Mexican churches, built on and with the remains of temples of indigenous peoples. You just have to look at Cholula , where the Spanish built the Church of Santa Maria Tonantzintla where the temple of Tonantzin used to stand, the goddess of the earth to whom the devotees entertained with fruit as an offering. Inside I found a carving with the features of a pre-Christian goddess and surrounded by juicy presents.

Once outside, I headed to the Great Pyramid of Cholula or Tlachihualtépetl . Next to its pyramidal base, the largest in the world, a vendor offered me something "appropriately" pre-Hispanic: grasshoppers (fried grasshoppers seasoned with lime and chiles) . I bought a bag, sat down to reflect and, while eating insects like pipes, I threw my latest theory in the trash. How something that tasted strangely like fried onions, only with more legs, had become part of the Mexican gastronomic culture? It had to be a thing of the ancestors.

Which led me to a new and improved theory. here has been eaten mole, tamales and tortillas long before the arrival of the Spanish . What makes Mexican cuisine peculiar—as well as delicious—is the indigenous influence. the great and vast aztec empire he enjoyed an equally grand and vast meal. In fact, its last emperor, Moctezuma II, would have eaten better than his European contemporaries. He sipped chocolate and vanilla beverages in gold goblets. Every day fresh fish from the gulf and ice from the highest volcanoes were brought to the royal palace. In each of his meals he used to taste about 30 different dishes, among which were his favorites: partridge, rabbit, venison and wild boar.

I am not going to score a point for this new theory, since it is what a grandmother would surely answer if you asked her why the tamale you just ate is so good. She would tell you that those places in Mexico that have characteristic dishes are the Valley of Mexico, Yucatan and Oaxaca, those that sit on the land once occupied by ancient civilizations (Aztec, Mayan and Zapotec).

Stall in the Mercado del Carmen in Puebla

The greatest exponent of this pre-Hispanic theory is Martha Ortiz , the high priestess of Mexican cuisine who lives and works in the heart of the ancient Aztec empire, known today as Mexico City. Known as much for her sharp look as her exquisite cooking, Ortiz describes what she does with food as “paint with the ingredients of Mexico” . She toured the country's markets from top to bottom and learned ancient techniques from the women. Such as the finest nuances when grinding ingredients in the ubiquitous, and not to mention pre-Hispanic, mortar known as molcajete . "Most people grind too fast," she says.

Her cooking seems to be inspired little by ingredients and trendy techniques and more by doses of history and passion in equal measure. "Corn," she proclaims, "tastes like the sun." A Mexican sauce cannot be made "without touching the stone," she points out.

The chef took me to Xochimilco , an ancient city that is part of the capital and is today a neighborhood known for its canals and colorful barges, something like an Aztec Venice . Her market looks like an amusement park of Mexican specialties. Many have not changed over the years, for example, there is an elderly woman (82 years old) who has been selling frog leg tamales here since she was 24 years old . I ordered one and he served it to me in a tortilla that I had never seen before, as if carved from a deep blue cornmeal. She covered it with cactus leaves and sprinkled it with blue cheese, a pre-Hispanic base with a very European touch.

Pork and red chili tamales from a roadside stand in Texcalyacac

For dinner I did a gastronomic turn of 180 degrees. I left the anthropological study and headed for the extraordinarily charming, modern and luxurious countess neighborhood , whose streets are lined with trees, boutiques, Art Deco apartments, and restaurants, lots of restaurants. If you look at appearances, life in the Countess consists of dressing well and going out to dinner. The lucky ones dine at merotoro, a cool and relaxed place whose chef, Jair Téllez, is a native of Baja California.

The next day, before going to the airport, I decided to stop by Barbacoa El Calandrio in search of the quintessential Mexican hangover remedy. This place is located in a neighborhood called San Martin Xochinahuac and attracts all kinds of customers, from working people to rich guys who get out of their sports cars to buy lamb (this is prepared inside maguey leaves and cooked slowly over charcoal for 16 hours).

Panela, cheese, mushrooms and pumpkin flowers at the El Carmen market

Before launching myself into a mountain of delicious shoulder tacos, I received my medicine: the broth released by the preparation of the lamb. As I drank it and steam filled my face, my mind drifted to Gaia, the Cuernavaca restaurant that now seemed like a distant memory. I took advantage of the dessert (spiced banana tart with coconut ice cream) to ask their chef, Fernanda Aramburo, her own theory about Mexican food. By then I had already discarded the peasant culture, but when the lamb broth made me a person again, I recognized the wisdom and beauty of her words. "Culture and tradition Aramburo said. If something is cooked with love, if the hands that cook love, that love will be felt in the mouth” . I took a piece of lamb and then a tear fell down my cheek. It must have been the chili. *** You may also be interested in...**

- Bravo Bogota! New emerging gastronomic power

- Emerging gastronomic powers I: Mexico

- Emerging gastronomic powers II: Peru

- Emerging gastronomic powers III: Brazil

- Emerging Food Powers IV: Tokyo

- Everything you need to know about gastronomy

This article is published in the December 68 issue of Condé Nast Spain magazine.

Chiles, peas and eggs in the Mercado de El Carmen in Puebla