Vintage in Champagne (Moët & Chandon). October 1941

“Being French means fighting for your country and its wine” (Claude Terrail, owner of La Tour d'Argent).

With this declaration of intent it is clear that the French spirit is given over to wine, is a leading part of its grandeur, and that defending him to the extreme is in his DNA.

For this reason, when one of the greatest threats that a country can suffer, war, hovered over the Gallic people, wine also became one of the concerns of the resistance of its people.

The dark episode of Second World War left in France a multitude of stories, small and not so much, about how the Gauls defended tooth and nail the best of their cellars of the tireless German looting between 1940 and the end of the occupation.

Saint-Emilion, one of the main red wine areas of Bordeaux

THE WEINFÜHRER, THOSE PEOPLE

The Germans once occupied the main French wine-producing areas, and to avoid the huge looting of the troops (the regime needed not only wine, but also the benefits that it could generate), the figure of the weinfuhrer.

The weinführer was the official who supplied the Third Reich with large quantities of French wine and functioned as intermediary between producers and regime.

In France it was named one for each of the main producing areas, from Bordeaux to Burgundy, passing, of course, through Champagne.

Vineyards in Champagne, one of the main producing areas

In Champagne this officer was Otto Klaebisch, a guy born in Cognac, so, at first, his knowledge of wine and brandy was seen as good news… but nothing further.

According to Julian Hitner in the wine magazine decanter, Herr Klaebisch was quite greedy: once he arrived, he settled in the house of one of the great Champagne families, Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, and neither short nor lazy, he demanded up to 400,000 bottles a week for the Reich.

Of course, the maisons didn't like this at all and means were sought to avoid entirely satisfying the cunning Weinführer.

Otto Klaebisch, the Weinführer of Champagne

Some they labeled wicked champagnes with labels from their prestigious cuvées trying not to notice but… oh! The officer's nose was very fine and he was able to detect it, mounting, of course, in anger.

Relations between the producers and Klaebisch were strained until the Count Robert Jean de Vogue then director of the house of Épernay Moët & Chandon, established a warm relationship with the German that was able to prevent total looting of the kilometer-long cellars of the maisons, also creating an organization that still protects the interests of Champagne producers: the CIVC, Champagne Wine Interprofessional Committee.

Thus, the invader had no choice but to go through this organism, where all the producers were considered on a par, for their commercial transactions.

Relations improved so much that houses were even allowed to sell to some establishments and export, yes, export to neutral countries.

The Champenoises stood united in the face of adversity to preserve the reserves of that wine that, as Napoleon said, "in victories you deserve it and in defeats you need it", in a leonine way.

The Gauls defended tooth and nail the best of their cellars from the tireless German looting

Even the French resistance of the Marne department, to which the Champagne region belongs, passed information to British intelligence of what had been done a somewhat special assignment, some bottles of champagne conscientiously corked and packed to travel "to a very hot country"... which turned out to be Egypt, where General Rommel was preparing an offensive.

The champenoises did not stop trying to confuse and deceive their weinführer until Klaebish returned home, crestfallen, but leaving a debt of millions of francs.

On the road to defeat he had sent Monsieur de Vogüé to jail, that he spent more than a year in a concentration camp and could not return until the occupation ended. the case was protect what really mattered…the champagne.

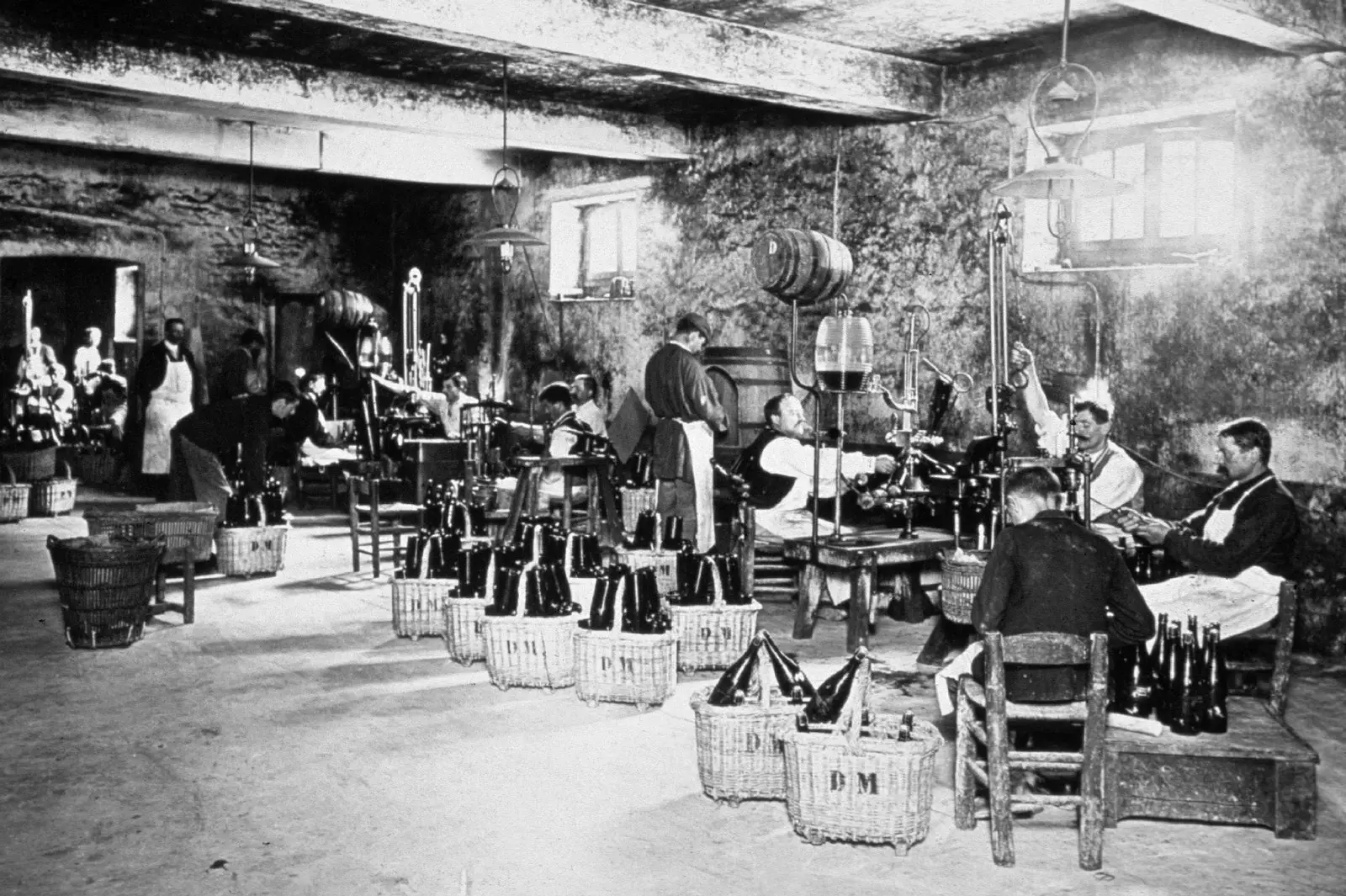

Disgorgement phase of the bottles at Maison Ayala (1930-1950)

When liberation came, Europe was able to celebrate with champagne thanks to happily hidden bottles from the german siege until then.

Gone were years when you had to fool the germans with silent corks or dirty bottles and shipments that did not arrive, erecting false walls that hid valuable items in their cellars or, as the Bollinger house did, labeling his best cuvées with a word that put the bravest back: poison.

BORDEAUX, STEADY IN THE FACE OF THE ENEMY

The Weinführer of Bordeaux was Heinz Boemers, tells Stefana Williams in Decanter about the stories contained in the interesting book Wine&War: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France's Greatest Treasure, by Donald and Petie Kladstrup, he was Heinz Boemers.

Boemers was a guy who had been an importer of Bordeaux wines and kept contacts with French wine dealers, especially with 'Uncle Louis', Louis Eschenauer's family name.

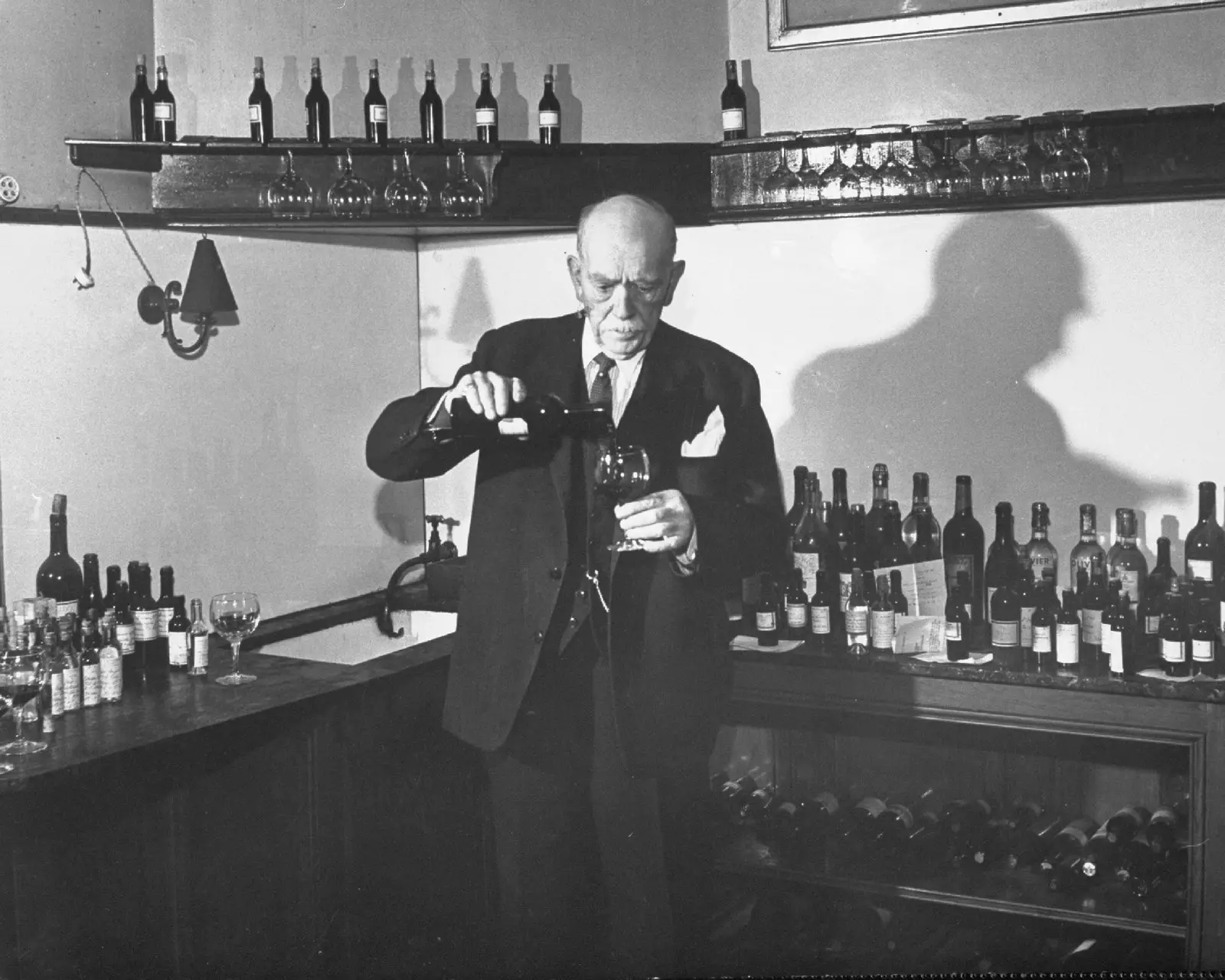

Louis Eschenauer, better known as Uncle Luis

Tito Luis had come to sponsor one of Boomers' children, such was his closeness. this cordiality caused trade between producers and the invading regime to be fluid, more than anything thinking that, at the end of the war, the business would have to be restored again and there was no point in making enemies, especially among the producers of one of the most prestigious (and valued) wine regions in the world.

But the devaluation of the franc played against the transactions for the French, that they were losing money profusely, and it was a matter of time before the black market made its appearance, because it was more viable to buy contraband than through normal channels.

A small disaster that did not help Bordeaux wine to stay too afloat during the war years, although it did not sink completely either.

With a frank weakling like then, the Bordeaux people looked for the laps to take advantage of the forced trade with the Germans and they did not hesitate to dust off mediocre vintages to empty warehouses.

Place Pey-Berland in Bordeaux during the German occupation

The problem is that there was no neither labor nor elements to keep the vineyards in good condition, so the years of the war were, unlike some vintages in Champagne, of very low and mediocre harvests.

In the region, as in so many other war scenes where wine was made in peacetime, there were also some episodes in which the French hid behind the walls of the restaurant Le Bouchon (the cork, in French) their best bottles, as the journalists Javier Márquez Sánchez and Rodrigo Varona tell in one of the chapters of their book Fuera de Carta.

What they say could be a sequence from a Nazi movie with its tension and everything, but it was real. Of course, if you want to know the rest, you will have to look for it in the book.

The Germans, defeated, it was time to leave and the risk was that the defeated troops would blow up routes, bridges and highways, something that, again, was partially prevented by the pleas of Uncle Louis Eschenauer to Kuhneman, commander of the Bordeaux naval base.

Some pleas that, later, played in favor of the négociant when he was put on trial, accused of doing business with the Germans, something everyone did back then, only Louis liked to brag about it too much...

Wine bottling in Bordeaux in the 1940s

THE END

In Wine and War you can find fascinating stories about the war and French wine, like the one told by the authors in the introduction and which recounts a moment at the end of the war, the episode in which May 4, 1945 (yes, coincidentally, also coincides with Star Wars day, only then the war It was in another galaxy...) Bernard de Nonancourt, then a tank pilot in General Philippe Leclerc's second division and later one of the newest presidents of the Laurent-Perrier champagne house, he found himself, blowing open the door of a hidden cave in a Bavarian mountain, where the darkly famous Kehlsteinjaus, or 'Eagle's Nest', half a million bottles of the best wines ever made, great vintages of Château Lafite-Rothschild, Château Mouton Rothschild, Château Latour, Château d'Yquem and Romanée Conti, most of them, of XIX century.

He was struck by the hundreds of Salon boxes from 1928. But the most curious thing was that the boxes belonged to a guy who didn't care much for wine and didn't even drink himself: Adolf Hitler.