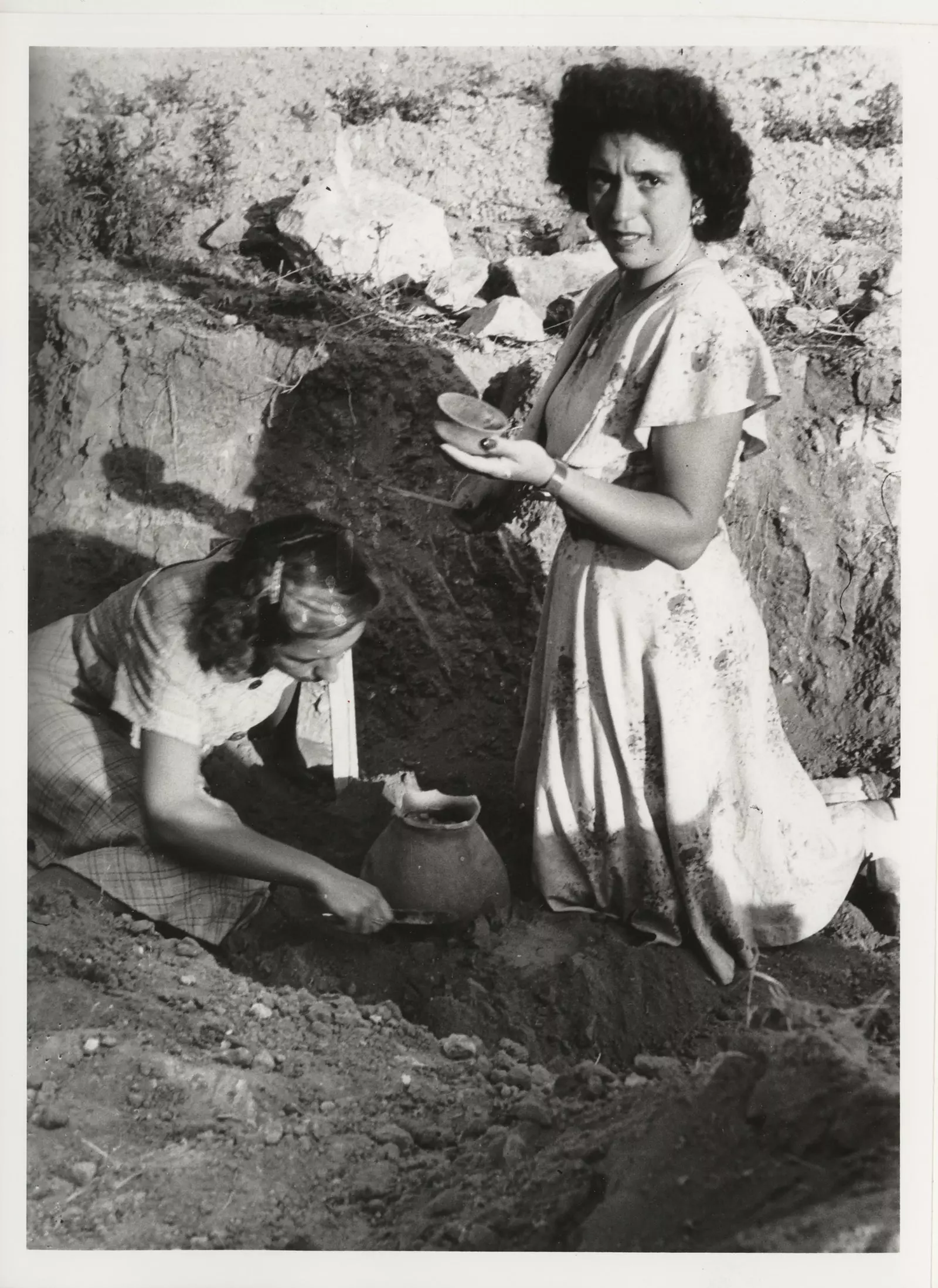

The sisters Julia and Nieves Sánchez Carrilero in the excavation of the Iberian necropolis of Hoya de Santa Ana

That he ‘Archaeologists’ of the headline has a capital letter where grammatically it does not apply, it is not a typo. He is intentional. It is the way to emphasize that This project is about women and Archaeology, about women in Archaeology, and more specifically to trace the "women's paths in the History of Spanish Archaeology" in the 19th and 20th centuries.

And it is that, as indicated Margarita Diaz-Andreu, ICREA research professor at the University of Barcelona and principal investigator of ArqueólogAs, “in the histories of archeology they have been forgotten”.

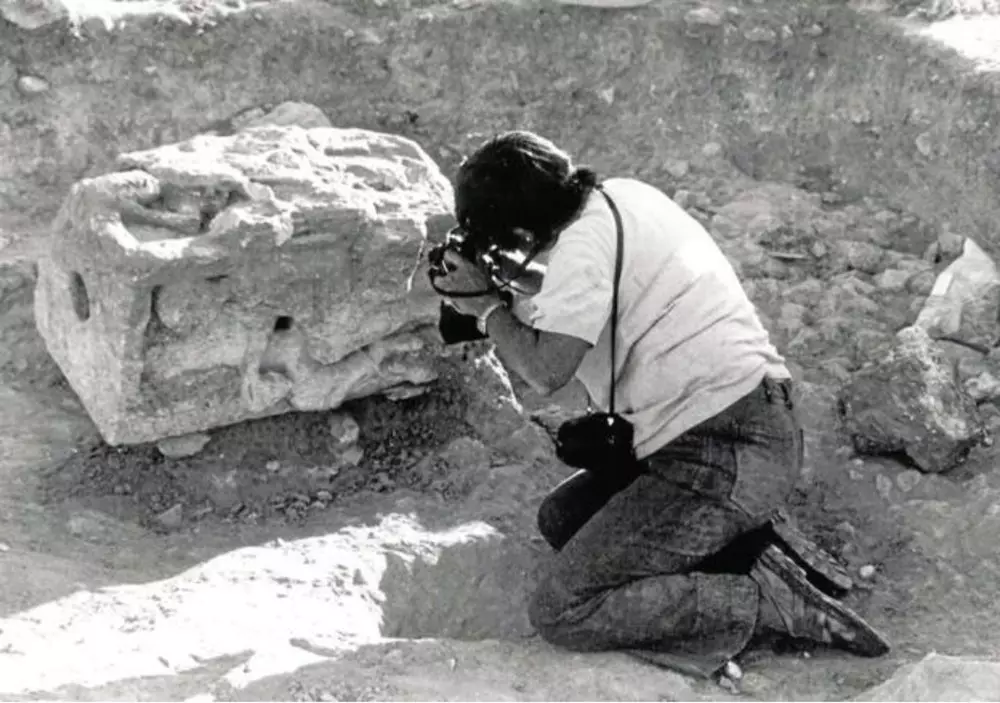

The archaeologist Ana María Muñoz Amilibia (1932-2019)

Recovering her memory in this discipline is the objective of ArqueólogAs, a research project subsidized by the State Research Agency that was launched a few months ago.

In this time, they have already held an online congress (Recovering the memory of women in the History of Archaeology: methods and techniques), they are preparing the next one for March 12 and 13 (Voces in crescendo: del mutismo a la hoarseness in the history of women in Spanish archaeology) and on the project website they periodically publish biographies of the 'pioneers' . They go for 44, but on their list there are already almost a hundred and a half names.

“The most surprising thing has been realizing that the large number of women who had a role in the discipline. I had always spoken in publications of a few, but there are many more than we had never heard of”, Diaz-Andreu explains.

Thus, when browsing the section 'pioneers', one discovers, among others, Encarnacion Cabre, the first woman in Spain to carry out extensive archaeological field work; that the thesis that Gloria Trias published in 1967 on the study of Greek ceramics in the Iberian Peninsula marked a before and after and that even today continues to be the subject of consultation; or what Anna Maria Munoz She was the first woman to win a professorship in Spain in the field of Archeology in 1974: the Chair of Archaeology, Epigraphy and Numismatics at the University of Murcia.

Archaeologist Mercedes Vegas working on the identification and classification of Roman pottery

Nevertheless, Archaeologists It's not about inventing heroines, but about “approach with a critical eye the causes of this invisibility and ask ourselves if it is the perspective with which we have written history that has led to not see as a problem that the group of women is silenced who have already worked for decades in professional Archaeology”.

After this work is a group of nearly 20 researchers from universities (Barcelona, Madrid Complutense, Alcalá de Henares, Alicante, Malaga and the Higher School of Real Equality, Humanities, Communication and Culture), museums (National Archaeological and Casa Bonsor) and independents.

All of them form an interdisciplinary team that ranges from the different branches of Archeology to Contemporary History, passing through that of Art. Mostly women, but there are also some men. “The lack of women in the histories of Archeology should not only be a concern for us, but also for them it must also be essential that historical reflection be critical of the past of the discipline”.

The archaeologist Milagros Gil-Mascarell in the Iberian tower of Foios (Lucena)

They use archives, interviews and publications. Geographically, they aspire to go beyond Madrid, Barcelona, Andalusia and Valencia , where towards the 90s special attention began to be paid to the history of women within Archaeology. Temporarily, the objective is to delve into the nineteenth century, moment in which this discipline is professionalized in Spain and in which there is a gap in research; as well as document the time closest to ours with testimonies from the generation that is now leaving active professional life.

“Women began to join the profession in the twenties of the 20th century. (...) In 1928 the first woman [María del Pilar Fernández Vega (1895-1973)] entered to work in an Archeology museum (the National Archaeological Museum) and since then others have followed her. When they had to go to the provinces, they were the only ones in charge of the museum and thus we see several, even in Franco's time, who directed their institutions with great success. But nor are they mentioned in the histories of Archaeology”, Diaz-Andreu says.

That we find the first female archaeologists in the field of museums is not by chance. “In them they have a more discreet role, relatively less public. It is more acceptable to observe them taking care of collections or assembling showcases than in the arena speaking in public. But as the 20th century progresses, new generations of women are gaining access to positions”.

Group image in which some of the women who worked at the National Archaeological Museum appear

Currently, Díaz-Andreu considers that progress has been made in the integration of women in Archaeology, although she points out that the number of women in the different stages of the profession has a very pyramidal structure. "They are the absolute majority at the university, but as the professional career advances, their proportion decreases until it becomes clearly lower in the higher echelons."

Collecting the biographies of these women will allow Archaeologists complete the story and continue weaving a story that covers different eras and in which both professional paths have a place (women who worked in universities, research centers, museums, the administration of Archeology or in commercial Archaeology) as non-professional routes (work in societies and associations, in the dissemination of Archaeology, those who served as support for them as volunteers, wives, friends or others whose financial means simply allowed them to be interested in antiquities without earning a salary).

The sisters Julia and Nieves Sánchez Carrilero

“Only by acknowledging that the work of women in the study of Antiquities has been silenced and by trying to answer the question of why this may have happened, can we try to make the historical discrimination that women have suffered in Archeology come to light. disappear and that the young women of the new generations who are now at the university perceive their great potential as the professional archaeologists of the future”.

And it is that, if perpetuated, this invisibility of women in the field of Archeology it not only has consequences in the present, but could continue to have them in the future.

“It represents a veiled message to the new generations that they are worthless, that it is men who serve for discipline, that they know how to manage, publish, think, interpret and direct better than women. We know this is not true and that society is losing enormous wealth by preventing women from contributing to scientific progress”.

“It is not only that their incorporation into the professional world leads us to a fairer society, but also that it is precisely the diversity of ways of doing and thinking that will help institutions to advance in a more balanced way”, Diaz-Andreu reflects.

Change perspective to complete the picture, for a matter of justice and to rethink a past that has often been told incomplete, leaving its female protagonists on the sidelines of the story. When this happens, when you look at it with different eyes, even India Jones's totem ceases to be sacred (Amy Farrah Fowler's word - The Big Bang Theory).