Nellie Bly, the intrepid reporter

Nellie Bly she testified when she was fourteen against an abusive stepfather. Since then, she has advanced solo to become America's most famous journalist.

In 1885 it was unusual to hire a woman in a newspaper to cover current affairs, but her letter in response to a column published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch titled: ** "What's a Woman Good For?" **, she earned him a job offer from the editor. Nellie was then 21 years old.

under the pseudonym helpless orphan, she treated harshly working conditions for women in factories and her vulnerability in divorce proceedings. The industrial oligarchy of the city did not take long to react and its management tried to displace it to theatrical chronicle. Her reply was a slam.

She got a job at new york world, she known for her line of research. She there she took to the last consequences of her way of doing journalism.

72 days were enough to go around the world

In a boarding house in the city, she pretended to be crazy and got herself taken to the Blackwell's Island women's asylum. She spent a week there she published an article in which she exposed the brutality of the treatments to which the inmates were subjected.

Nellie embodied the gonzo journalism a century before it was baptized by a transgressor fully integrated into the system: Hunter S.Thompson.

According to this approach, the journalist participates in the news as one more actor, which causes a personal and subjective bias in the story.

So did Bly when she, after the success of the Blackwell's Island report, she read Around the World in 80 Days, by Jules Verne. In this novel, the French writer had put aside science fiction to illustrate the possibilities that he offered the transport revolution in the 19th century.

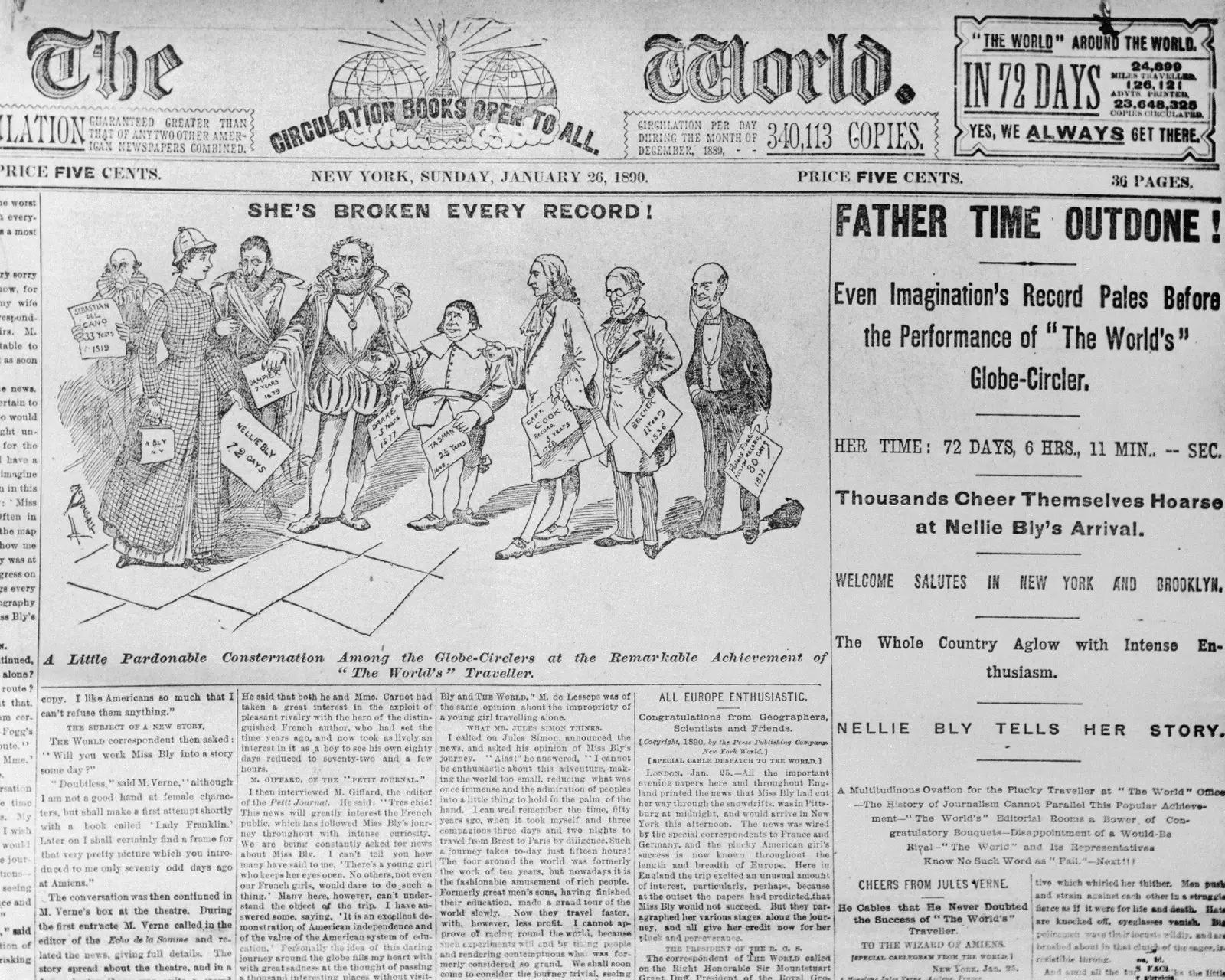

The World Newspaper (January, 1890)

The idea of her caught on with Nellie and she proposed to her publisher beat the deadline proposed by Verne. “A woman would need a protector. Only a man could do it”, was her answer.

Bly's replica portrays the spirit of her. “Get your man going,” she said. “I will do it the same day for another newspaper and I will beat him.” Her argument managed to convince him.

She dispensed with trunks and she compressed the essentials in a bag that today would be admitted as cabin luggage. She detailed her content in the article she published at the end of the trip: a change of underwear, a toiletry bag, paper and a pencil, a nightgown, a blazer, a bottle and a cup, two hats, three veils, some slippers and handkerchiefs

She did not change her shoes or her dress, although she did the necessary calculations to be able to wash it at various scales. Her only indulgences were a jar of face cream and a camel-hair coat. She admitted that packing that suitcase had been the biggest challenge of her life.

Nellie Bly was the pseudonym of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman

The journey began in Hamburg American Line dock in Hoboken, New Jersey, where she boarded the Augusta Victoria transatlantic, the fastest of the moment, bound for London.

On her way to Paris she made a detour to Amiens, where Jules Verne lived. The writer received her kindly. “If she makes it in 79 days, I will applaud her with both hands,” she stated. It is probable that she would never have imagined that a woman would put into practice the hypotheses that she had raised in fiction.

The journalist herself traveled by train to Brindisi, where she took a steamer to Port Said with which she crossed the Suez Canal. The network of scales of the British Empire took it from Aden to Colombo, in present-day Sri Lanka, Singapore, Hong-Kong, Yokohama, and across the Pacific to San Francisco.

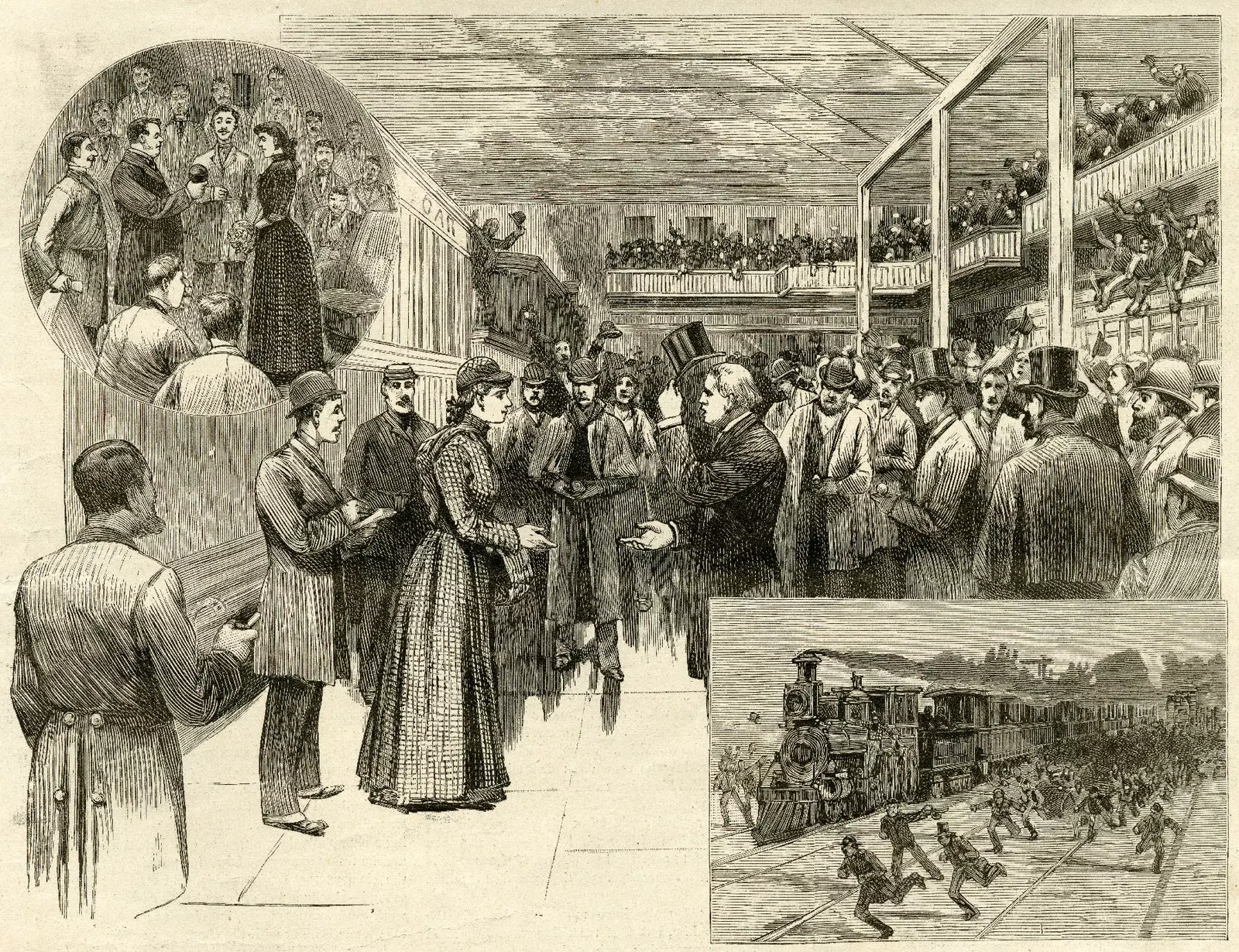

She reached the goal 72 days, 6 hours and 11 minutes. The final train journey across the United States was triumphant.

Bly's reception in New Jersey

Nellie had become famous. Her challenge was echoed in newspapers around the world. A competitor had embarked on the journey in the reverse direction for a competing outlet. When they told him of her existence, she Bly had already arrived in Hong Kong.

"I just run against time," she said. During the course of the trip, she sent telegrams to the editorial office that were received with the enthusiasm of Phileas Fogg's advances in Verne's novel.

The chronicle she published about the trip reflects Nellie's restless spirit. She overcame the seasickness aboard her by will and warded off men who approached her patronizingly.

It was inevitable that a 25-year-old woman traveling alone with a squalid bag as luggage would stir up rumours. Her deckmates between Brindisi and Port Said they assumed she was an eccentric American heiress.

Nellie Bly with her 'hand luggage'

As a journalist, she was drawn to the surprising and the morbid. In Canton she asked to be taken to the square where the executions were carried out and she detailed the modalities that were practiced there.

She looked at the crocodiles caught in Port Said like in a zoo and claimed that the men of Aden had the whitest teeth on the globe.

In fulfillment of the duties of a 19th century traveler, she made visits to temples in Ceylon and in Hong Kong she enjoyed the views from the Craigieburn Hotel.

Although her opinions are typical of her time, they do not show the contempt for the local population that is common in Victorian chronicles. Place on the same level the excessive consumption of whiskey and soda by the English and opium among the Chinese.

In Japan, she seems to find a place that arouses admiration for her. She talks about silent men and geishas who hide their arms up their sleeves.

Nellie Bly speaking with an Austrian Army officer in Poland

Nellie enjoyed the trip. As she stated in her chronicle: “Sitting quietly on deck with the stars as the only illumination and listening to the water slide by is, for me, paradise.”

Back in New York, her celebrity played against her. The doors to her gonzo reporting were closed and her feminine status prevented her from moving up in the newsroom. Her boss even denied her a raise.

disenchanted and bored, she met an iron magnate and married him. When she died, she took over the reins of the business. She came to register several patents, but a fraud led the company to bankruptcy.

She then returned to journalism at the New York World and, as a hallmark of her career, she became the first American to serve as a war correspondent in World War I, where she covered the eastern front.