Adventures and misadventures in the Atlantic Ocean

It is difficult to refute the fact that the human being has prospered thanks to his ambition to overcome challenges.

It is this innate non-conformity that has caused geographical, technological and even ideological barriers to fall, in order to advance one step further towards this modern society, clearly imperfect, but much more advanced than the one we had, perhaps, just a century ago.

However, many of these challenges have been raised simply by the purest love of adventure, freedom, danger and extreme situations.

These are the reasons that, mainly, moved the crazy adventurers who decided to cross the immensity of the Atlantic Ocean in the most precarious and risky ways possible.

Some dreamers who chose to live the greatest adventures of their lives emulating that Christopher Columbus who in 1492 discovered America. These are the incredible stories of him.

Go up, I'll take you!

THE INCREDIBLE “MARCOS”: TWO ITALIANS WHO CROSSED THE ATLANTIC ABOARD TWO CARS

Many may think that perhaps the Italians Marco Amoretti and Marco DeCandia were inspired by the Disney movie, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), to decide try to cross the Atlantic Ocean, from the Canary Islands to Miami, aboard a couple of floating cars.

Nothing is further from reality, and sometimes Genetics and family values have a lot to do with a passion for adventure.

The father of one of the boys, Giorgio Amoretti, had tried to cross the Atlantic in 1978, aboard a Volkswagen Beetle, but the Spanish authorities prevented him from going to sea. Giorgio, a provocative and nonconformist artist with bourgeois society, he was disappointed, but did not give up.

Twenty-one years later he wanted to try again, but was diagnosed with terminal cancer and His sons picked up the baton: Marco, Fabio and Mauro. A friend would accompany them: From Candia.

On May 4, 1999, hiding from the Civil Guard, the four young people set sail from the island of La Palma aboard a Taunus and a Passat filled with polystyrene -to help them float -, without a motor, without a mast, without a rudder and with only one sail.

Marco Amoretti and Marco de Candia, after spending 120 days at sea

On the roof of the vehicles – which were tied together so as not to get lost – they placed an inflatable boat in which they slept. The team completed 300 liters of water, dry food, a satellite phone (which, after getting wet, did not work for a month and a half), a VHF radio and a GPS.

After 119 days and more than 5,000 kilometers of drifting, two of the adventurers –Fabio and Mauro had to abandon the journey a few days after suffering severe intestinal problems– They reached the beaches of the island of Martinique, in the Caribbean Sea. That had not been his goal, but the Atlantic currents decided otherwise.

Arriving in Martinique, the feeling was bittersweet, because they had accomplished the feat and Fabio and Mauro were waiting for them there. Nevertheless, good old Giorgio had left this world while they were crossing the ocean.

The incredible “Marks”

During those 119 days in the Atlantic, the Marcos lived through storms, had problems with sharks, with the sun, with the waves and with a thousand other things, but they always remember the total feeling of freedom and adventure they experienced on the most unforgettable trip of their lives.

To this day, Marco Amoretti is still passionate about “automares” – As his father baptized those car-boats – and, for example, in 2017, he sailed from Genoa to Sicily aboard a Maserati with outboard motor.

He is now raising funds to continue the Atlantic voyage where he left off, completing the Martinique to Florida leg. He still owes it to his father.

STEVE CALLAHAN: 76 DAYS SHIPWRECKED IN THE ATLANTIC

Not all the great adventures of crossing the Atlantic were undertaken voluntarily. Steve Callahan is an American philosopher and naval engineer who, at 32 years old he was sailing around Europe in the 'Napoleon Solitaire' ('Napoleon Solo'), a ship designed and built by himself.

After traveling part of the coasts of England, France and Portugal, he arrived in the Canary Islands to resupply, carry out some small repairs and leave for the Caribbean Antigua, before returning home.

Steve set sail from the beautiful island of El Hierro on January 29, 1982, but the tranquility and enjoyment of the trip ended on the night of February 5, when stormy winds and a sharp blow to the hull he was rudely woken up.

Without even knowing what had happened (it remains a mystery to this day), Steve had to be very quick to launch his inflatable lifeboat into the water and transfer to it.

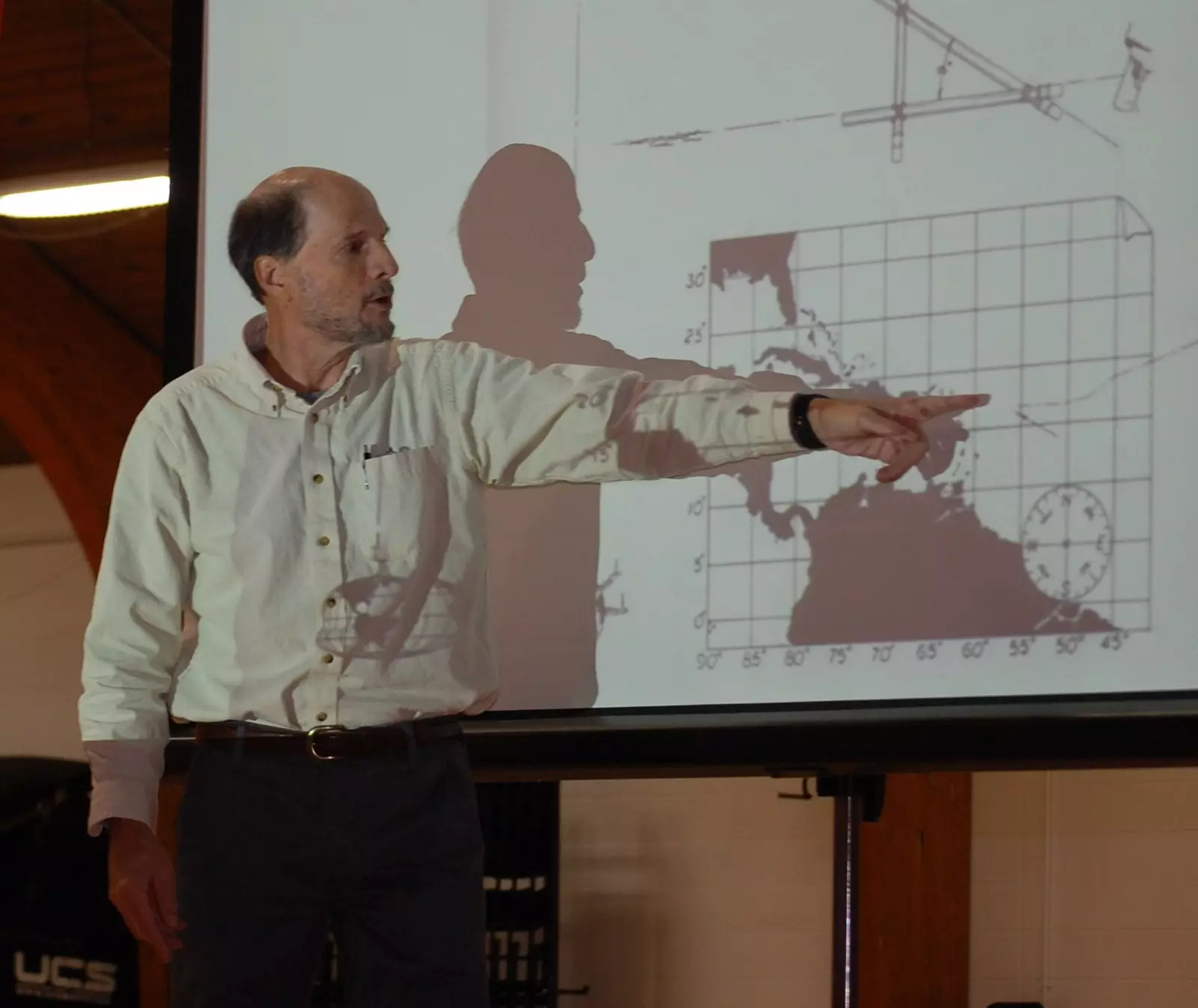

Callahan describes his drifting experience to students at North Yarmouth Academy in 2016

From the 'Napoleon Solo' he only managed to save some food, a container, some navigational instruments, a first aid kit, a torch and a survival book at sea, written by Dougal Robertson, who survived 38 days adrift after his boat sank in 1971.

That book helped Steve a lot, but it was mostly his skill and his mind that kept him alive for a long time. the 76 days he was adrift in the Atlantic.

As soon as his boat disappeared under the water in the middle of the night, he felt very alone, desperate and disoriented. He had to make a titanic mental effort not to sink during the first few days.

Steven Callahan recounting his adventure

Later, he began to develop his ingenuity and use the advice from Robertson's book to get drinking water with a solar distiller created by him, make a harpoon from the torch and practice exercises with arms and legs so as not to get stuck.

He endured storms, punctures (one of them caused by a shark that I tried to hunt down and which ended up letting go of the improvised harpoon, piercing the rubber of his raft), the inclement sun and, above all, the most brutal and absolute loneliness, until he was found by a fisherman off the coast of Guadalupe Island.

Over time, Steve Callahan wrote a book about his adventure—Adrift: Seventy-six Days Lost at Sea—and even he designed a lifeboat that was capable of covering all the real needs of a castaway.

A couple of decades later, that boat has been patented and built, incorporating such useful and basic things as a roof and a sail. He would have killed to have that little sail while he was lost in the vastness of the ocean.

CAPTAIN SWING

Adrift: Seventy-six Days Lost at Sea (Steven Callahan)

THE ATLANTIS EXPEDITION: CROSSING THE ATLANTIC ON A PRIMITIVE RAFT

In 1984, just halfway between the great sadness of the Malvinas and the overflowing joy of the "Hand of God" of the great Diego Armando Maradona, Five Argentines caught the world's attention by crossing the Atlantic Ocean on a primitive log raft, without a rudder and with a single sail.

The idea had been conceived in the imagination of Alfredo Barragán, a young law student who always believed that there were several similarities between some points of different African cultures and the cultures of pre-Columbian America.

This suspicion intensified after a trip to Mexico in which he was able to admire Olmec sculptures representing black men. Would it have been possible that African inhabitants had arrived in America some 3,500 years before the famous discovery of Christopher Columbus? He wanted to show that it was so.

He wanted to do it sailing from the Canary Islands to America aboard a boat as rudimentary as those that the ancestral Africans could have. The Atlantic currents would do the rest.

Far from being an expedition left to chance, Barragán spent months maturing the idea, forming the team and studying the possible navigation aboard the raft.

Monument to the Atlantis Mar del Plata Raft

They did not accept sponsorships to build the raft. The trunks were obtained, as gifts, from an Ecuadorian factory. The candle had a tradition, since it was nothing less than one of those of the old and distinguished Frigate Libertad, donated by the Argentine Navy.

Finally, they created a raft 13.6 meters long and 5.8 meters wide with which they would depart from the port of Tenerife on May 22, 1984.

In addition, they managed to embark on the adventure to Félix Arrieta, the cameraman who recorded the expedition, about which a documentary film was released in 1988.

The trip lasted 52 days, arriving at its destination in La Guaira, Venezuela, after experiencing endless adventures at sea. Today, you can visit the mythical raft in a museum in Dolores, Barragán's hometown.

In Mar del Plata – the place where the young man studied Law and where the idea of the expedition was shaped – there are a sculpture that also pays tribute to Atlantis. The phrase that says it reflects the purest motto of the adventure: "LET MAN KNOW, THAT MAN CAN".