A route through Spain from bakery to bakery

Could be confused with James Rhodes if we stick to the passion that he puts into his defense of the particularities and differences of our country. But luckily, or unfortunately, Iban Yarza he is not so media, although he has done his little first steps on television and is Known as the great bread guru.

His latest book, which is now in its third edition, continues on the same path as what we already knew about this pro panarra: Spain is a place with an incredible culture and it is necessary to make it known.

village bread is the name of a volume that mixes the best of Anthony Bourdain's road movies; that little initiatory point that the old Lonely Planet had, the ones that really discovered places that did not appear in the usual travel guides; and some wisdom and good knowledge a la Alan Lomax, the mythical ethnomusicologist that toured the entire world to capture how the most remote cultures on the planet sounded.

But Yarza, in the end, is much more local and close. The referents of it must be found in Felix Rodriguez de la Fuente, José Antonio Labordeta, Sergio del Molino (the author of Empty Spain) or Joaquín Díaz, another folklorist who has managed to enlarge the idea of a country that many of us have.

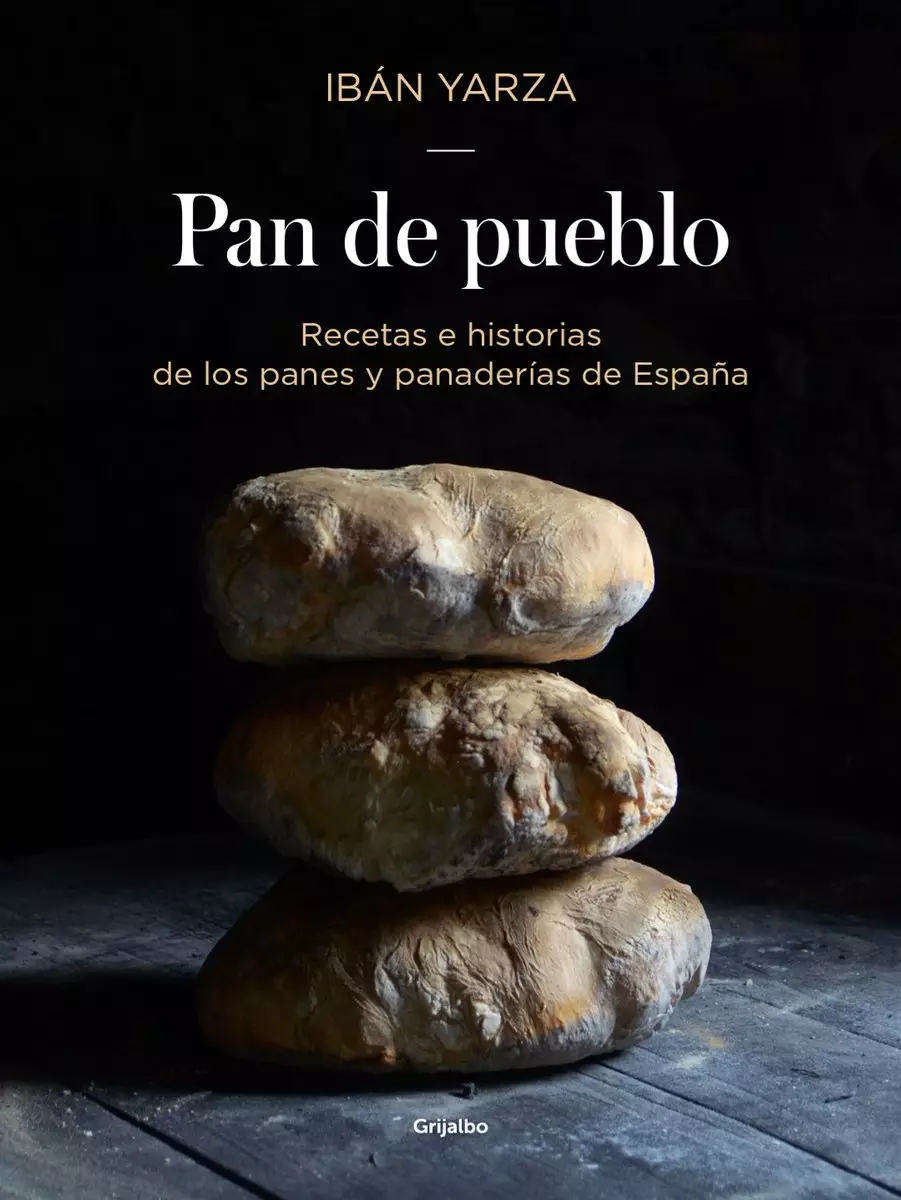

Pan de Pueblo, a journey through the traditional breads and bakeries of Spain

People's Bread: Recipes and stories of the breads and bakeries of Spain en a trip, through more than 25,000 kilometers of regional roads, where tradition is intertwined with the present.

A particularly delicate moment for bread. Well, Although more than 350 varieties appear, some are about to disappear because of how little care we are taking with them. Conservation, militancy and reality. A fundamental work if we want to know what is happening right now in the other Spain.

How did you propose the book to the publisher so that in the end there were almost 300 pages with so much information and images?

The book at the beginning was going to be half and it was going to have many recipes. But that fell short. As soon as I started going places and taking photos I saw that this had a lot of potential. I managed to convey in the different meetings I had with the publisher that bread is a cultural aspect.

In the end, a very complete book has been left: there is history, there are recipes, there are features of ethnography... I try to play many clubs. But the important thing was to reach as many people as possible and convey the importance of bread and its culture.

More than 350 varieties of bread appear in the book Pan de Pueblo, some in danger of disappearing

Tell me the whole process of the trip. The work behind it is amazing, community by community. How did you get organized?

I think if I think about it again I don't do it. You do not know the money I have left and the hours I have been in the car from one place to another. I live in Ibiza, on an island, so everything becomes a little more difficult. If I want to go to Cuenca one day I don't take the car and go there. Everything required a meticulous previous work.

I concentrated on areas and carried out preliminary research work. Research everything. I prefer not to add what I have left in trips and books. If there was a small ethnography notebook from Guadalajara, there it was. The documentation has been very large.

But going from one side to another. How did you do it? Your story shows that you haven't slept for many hours...

The trips were really crazy. I had been wanting to write the book for a long time, but the fact that Spain is very big always put me off. If you give 50 provinces three loaves per province, you would need several years to do it and not live.

"In the end it has been a very complete book: there is history, there are recipes, there are features of ethnography...", comments Ibán Yarza

And you did it in less than a year.

He'd pick an area, fly to the nearest airport, rent a car, and dash to the bakery where he had an appointment. Those eight or ten days I slept an average of three hours. Two hours many days. I was trying to concentrate a province in one day, which is absolute madness.

In A Coruña I made 500 kilometers from bakery to bakery. In Cáceres the same. Keep in mind that the baker's job is at dawn. I got up at two in the morning and went to see how they made the day's baking.

You also had to take photos and conduct interviews. That you never knew how it would work. What did you find?

There was always a very good disposition. If you look closely, each chapter tells a different aspect of the bread and what has happened around it. The baker told me a story, the techniques, the recipes... This at so many in the morning, to then go to another bakery in which I had an appointment.

And from then on the day was a continuum from road to road. My idea was to get the greatest diversity of bread possible, which has a lot to do with the diversity of customs in each region.

What was your criteria for choosing the different bakeries and breads that appear in the book?

I see and read about bread, but I don't know everything about bread. It is absurd to say that you know everything about bread. I relied a lot on friends who were bakers or flour distributors that I had scattered throughout Spain. So I was pulling people from the area.

But then all that had to be sifted through, because there were many things that were recommended to me that later didn't interest me. I also didn't want to show equal loaves. For example, in Cantabria a curious thing happened, almost all the outstanding bread was concentrated in the same area. That was a problem for me, because all the breads were very similar. I didn't want to make five identical cakes. What in the end he did was Palencia, Burgos and he was going down.

Another of the greatness of the book is the variety of criteria that you have managed to convey. At a time of total uniformity, where it seems that the "official taste" is so marked, you have managed to give value to each variety. Was it very difficult for you?

I am from Bilbao and there is no candeal there. However, the candeal is the bread what else is there in all of Spain. This bread does not belong to the taste that I have known, just like the spicy curry or the sweet and sour, but you must get used to it. There are breads that should be appreciated for different factors: their flavor, their texture or simply because they are rare.

A clear case is the bread from the Balearic Islands, where you live, which has no salt.

That's how it is. At the first bite people say "this has no salt". And as time goes by, you appreciate that those breads are of such a purity that the salt bothers them. Sounds like a great lesson to me. These are things that are not so obvious.

In the end, bread is the homeland of each one, even if you know there are better ones. What I have tried with the book is that people open their minds and do not think that their bread is the best.

What are the most curious or rare breads you have come across on this trip?

More than with curious breads, I have come across techniques. I had read in many places how man began to make bread. In those early days, fermentation was unknown and unfermented cakes. Unleavened cakes, like the ones they give you in church when you receive communion. They are breads that are not fermented, they do not have bubbles.

This is something you read in prehistory books, but you can't imagine that there are still places that continue to make bread this way. And yes, in Alicante I have seen it. It is as if you find a countryman in Alicante making a flint weapon. There are ancient techniques that are still in use.

The large loaves, typical of Cillamayor, at Panadería Jesús Martín

All photographs in the book are yours. There are more than a thousand. Many of them are of a beauty that is difficult to describe: they are authentic, far removed from the Instagram effect. How did you get it?

You won't believe it but Many of the breads that appear in the photos were given to me by bakers to photograph. So I found that I couldn't eat them until I got to the hostel on duty. The white backgrounds that can be seen are the quilts of pensions throughout Spain. If you look closely, you will see that many backgrounds have seams or flowers.

Others are taken in bakeries, This is the case of the loaves that appear on the cover of the book. That day I was in a communal oven in El Bierzo, it's not a posed photograph, black is soot. Those loaves for the general bakery school trend are ugly because they are irregular.

They are not heavy and are for home consumption. But they really are beautiful. I remember that when I posted it on Facebook a man complained: “they are the ugliest breads I have ever seen in my life”, he wrote. And it is true, they would not pass the test of an exam. But there is no gastroelitism.

That is another of the great values of the book. There is no elitism, nor nostalgia, nor is there something so typical of today as wanting to appear to be what one is not. What conclusion do you draw from your visits?

That we must be aware of the enormous heritage we have. Since the book came out there are already bakeries that have closed. That knowledge has already been lost. We must do something with all the culture councilors of the different councils throughout Spain. Especially from Galicia, which has a brutal bread heritage. It is unacceptable that Galicia does not have a multi-volume bread encyclopedia.

We must be envious of the French, the Swiss or the Italians. They value bread more than we do. The French have a law from the year 1993 in which they force you to knead, ferment and bake the bread to have your own bakery. The Swiss in the sixties set up a national institute dedicated to defending the culture and history of bread. We have a bread culture that is dying.

FIVE BREADS YOU SHOULD KNOW AND WHERE TO FIND THEM

Cañada, at David Muñoz Bakery _(Travesía de Perones, 3, Biel, Zaragoza) _

“Biel is just a hundred kilometers from Zaragoza, but, in the dark night of the eternal winding road, one would seem to be traveling through time escorted by deer, rabbits and wild boar around every bend. Barely a hundred souls inhabit this corner of Zaragoza that feels almost Pyrenean, secluded in an uninhabited corner of uninhabited Aragón. David Muñoz meticulously prepares the breads that his father Felix taught him: the glen and the bun bread. The name of cañada comes from the marks that were made in each house with a cane to later recognize them.

Large loaves, at Alejandro Iglesias Bakery (_Plaza Iglesia, s/n, Cillamayor, Palencia) _

Alexander Iglesias, forty-five years old, takes a round, golden loaf out of his wood-fired oven in Cillamayor while It dawns below zero at almost a thousand meters of altitude. This town of barely fifty inhabitants is in the northern limit of Palencia and announces its summits. The population has been greatly reduced, but the region lived for almost two centuries the hustle and bustle of the exploitation of coal mines”.

Easter cake from Bakery Moreno (Torreagüera, Murcia)

Easter cake, at Bakery Moreno _(José Alegría Nicolás, 2, Torreagüera, Murcia) _

"Easter cake is a typical Christmas sourdough, but nowadays it is consumed throughout the year. In Torreagüera, the Moreno brothers teach me this incredible elaboration. The crescent (bread dough) is mixed with large quantities of fried almonds, cooked sweet potato, orange juice, matalahúva grains and anise brandy. With all this load, the resulting dough is almost liquid and would not seem to be suitable for baking, but after twenty-four hours of fermentation the miracle works: a superlative product".

Loaf, at Montserrat Lopez Bakery _(B.º Central, 5, Quintana de Valdivielso, Burgos) _

“Baker Montse Lopez transfers cakes and loaves to the paddle with a flick of the wrist. I have not met many people with the ease and self-confidence with the shovel that this woman from Quintana de Valdivieso, in the north of Burgos, has. During the fermentation, the already formed pieces rest on the maseras (cloths), and it is common to use a small paddle to move them from there to the large oven paddle. Working alone, by force, Montse had to learn to skip that intermediate step, and giving the cloth a sharp tug, she flips the loaves, which spin in the air until they land on her master shovel”.

Mari and Montse, two generations of bakers in Quintana de Valdivieso, Burgos

Bread seasoned with anise, 100% Bread and pastry _(La Graciosa, 4, Playa San Juan, Santa Cruz de Tenerife) _

“In Playa de San Juan (Tenerife), alexis garcia he also learned the bakery at home. However, he always had a lot of restlessness, he wanted to learn and do new things, which sometimes collides with the more traditional plans of the family business, and practically led him to hate the bakery. In a reflective voice he recalls that he luckily had the chance to go to a bakery in Strasbourg, where he realized that he had wasted his time and saw what he really wanted to do. Ten years ago he opened his business, in which, in addition to bread, he makes a high-level pastry (Alexis is a pastry chef with the soul of a baker) ”.

Alexis García's bread with anise