The one-piece museum that tells the story of everyday objects

The film begins like this: February 28, 2021. A bearded man walks through a museum and stops in front of a display case. He opens it, inserts an arm, take the only metal object that is exposed and puts it in his pocket with a quick movement. Afterwards, he leaves the museum, walks away from the building and gets into his car.

After 10 minutes of driving, the man enters an underground garage, he closes the car and rides in an elevator while he feels the surface of the metal object without removing it from his pocket. The man gets out of the elevator, takes out some keys, opens a door, hangs his coat on a hanger and enters one of the rooms. It's a kitchen.

The man goes to the sink, grabs a scourer, turns on the faucet and rubs the object to the last of its cracks. He wipes it dry he opens one of the drawers, deposits it inside and closes it again.

Several hours later, he will open that drawer again, pick up the item, beat an egg with it, make a French omelette, and eat it using the same item. then and only then he will finally be able to confirm it: a fork works equally well both before and after it has become a museum piece.

THE ART OF BEING A DAILY OBJECT

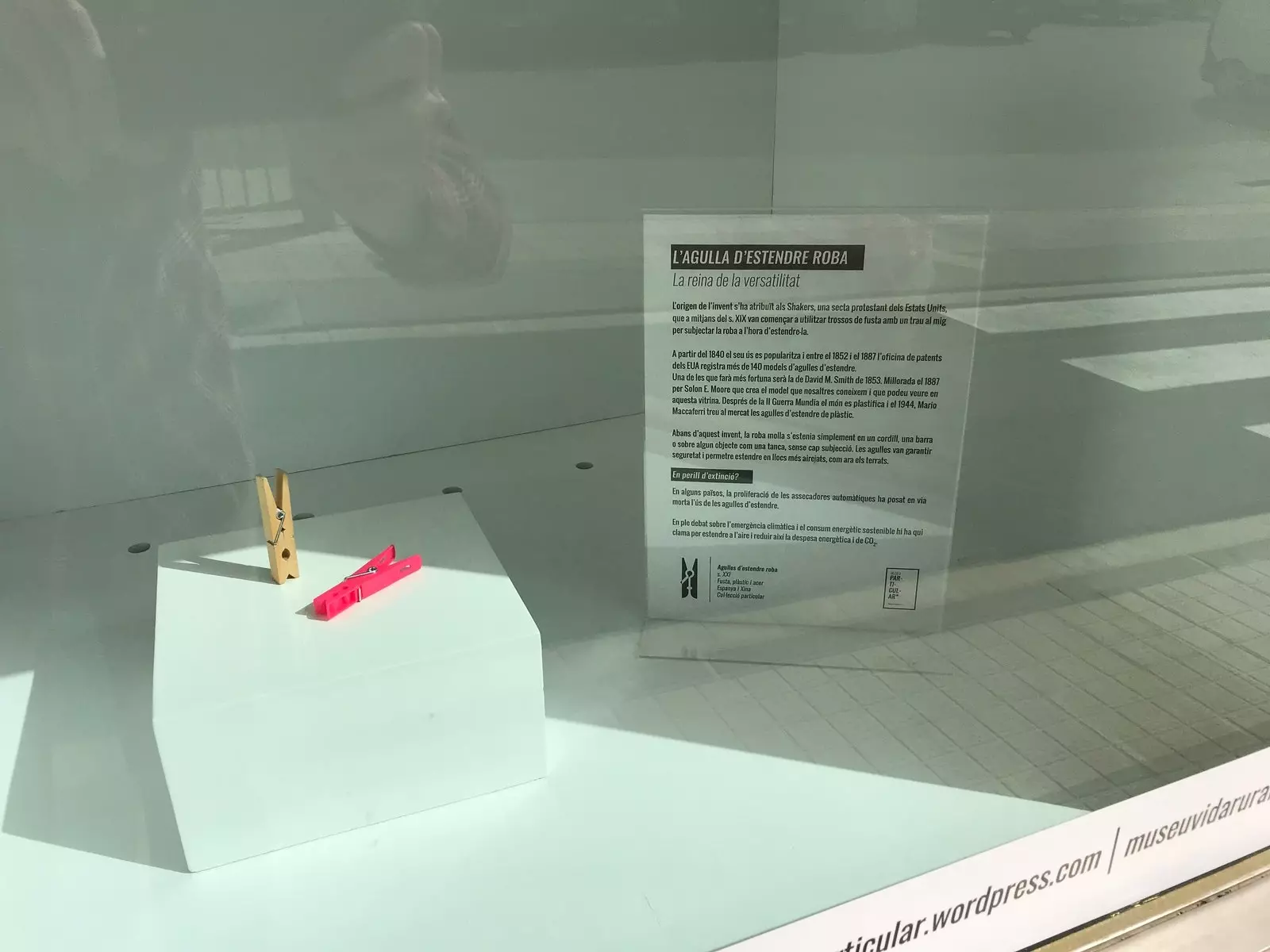

What do a fork, a tampon, a clothespin and a tin can have in common? Depending on who is asked this question, the answers can be as diverse as wacky.

If they ask Alex Rebollo Sanchez , his answer will be clear: each and every one of those objects has been museum pieces for a month. Specifically in the Private Museum of L'Espluga de Francolí, in the province of Tarragona.

Álex Rebollo is a historian, museologist and freelancer. He emphasizes the latter to facilitate understanding of the project that he began in February 2021: "to work in a museum I had to create it."

And it is that Rebollo is the architect, together with the art historian and museologist Anna M. Andevert Llurba , from the weird and wonderful Museu Particular: a museum of less than one square meter that exhibits one piece a month and whose "works of art" come from the drawers, cabinets and cupboards of Álex Rebollo's house.

What do a fork, a tampon, a clothespin and a tin can have in common?

The Museu Particular is defined on its website as a "space to give voice to everyday objects, discover their fascinating stories and, through them, reflect on them and –especially– on us".

According to Rebollo himself, the idea of creating this ethnological space to walk around the house arose "In the midst of a pandemic, during confinement, when I had a lot of time to think."

Rebollo explains that it was a topic that he had always been interested in and that was directly linked to his profession as a historian, a "work of asking questions": since when do we have a fork? How and why did the shampoo appear? Where does the plastic that we throw away every day come from and that appeared decades ago as a supposed option that is more resistant and durable than glass or ceramic?

Museum of Rural Life, physical headquarters of the private Museum

The Museu Particular began its journey on February 3, 2021, when Rebollo's fork (the Chosen One of all those who occupied his drawer) moved from his kitchen to an existing showcase in one of the facades of the Museum of Rural Life of L'Espluga de Francolí , official headquarters of the Museu Particular.

However, Rebollo's idea is that this minimum space located in the municipality of Tarragona crosses all the planes and expands exponentially. And for that there is only one solution: social networks.

In this way, Twitter and Instagram have risen as the operational arms of the project, the place where, through threads and publications, the story of the chosen everyday objects is told.

But Rebollo's intention is not only to discover and tell the story of these objects. He also wants to find questions and, perhaps, possible answers about us, the humans who use them. and that, depending on where we see them – in the trash can, in the cupboard, in a museum – we give them different meanings.

"The washing machine killed the public laundry room just a few decades ago. Will the dryer do the same for clothespins?"

WHAT IS AN OBJECT FOR?

"Now, my question is this: What happens when something no longer fulfills its function? Is it still the same thing or has it become something else? When you tear off the fabric of the umbrella, is the umbrella still an umbrella? You open the spokes, you put them on your head, you walk in the rain, and you get soaked. Is it possible to continue calling that object an umbrella? In general, people do. At most, they will say that the umbrella is broken. To me that is a serious mistake, the source of all our problems."

This objectual-existential diatribe was expressed by Paul Auster in his novel City of Glass. However, he was not the first human to ask himself these questions, but one more in a long chain that has been perpetuated throughout history. Among them, a Chinese emperor with a lot of curiosity and a lot of imagination stands out.

As the art historian and director of the British Museum tells Neil MacGregor in his book The History of the World in 100 Objects, The Qianlong Emperor of China (18th century) dedicated himself to collecting, classifying, cataloging and exploring the past, preparing dictionaries, encyclopedias and texts about what he was discovering.

One of the many things he collected was a jade ring or bi. The Qianlong Emperor began to wonder and investigate what it was for and, carried away by his imagination, wrote a poem about his attempt to make sense of that object (spoiler: its use is still unknown today).

Later –and here comes the geekiest part of the whole story– he had the poem written about the object itself. In that text, the emperor concluded that the ring had been conceived to serve as the base of a bowl. So, very worthy of him, he planted a bowl on top of it and gave it this new use.

What can be an umbrella apart from an umbrella? And a jade ring? At what point do they go from having one function to acquiring another? These questions, which would launch us headfirst into a premium version of the mythical TVE program from the 90s Don't laugh, it's worse (I just felt like a museum piece) with Pedro Reyes and Félix el Gato spinning around the emperor's ring, They only make sense when an object has lost its meaning, when the society to which that object belonged disregarded it.

And this, when it happens, is an absolute tragedy, because that object told a story about that society. A story that became forgotten.

As MacGregor explains in his book, an ideal history of the world should unite texts and objects, especially "when we consider the contact between literate societies and non-literate societies" where "We see that all our first-hand accounts are biased, they are only half a dialogue." And he finishes: "If we want to find the other half of that conversation, we have to read not only the texts, but also the objects."

It is in that space prior to the tragedy of oblivion where they appear the ethnographic museums, museums such as the Museu Particular or the Museu de la Vida Rural. The difference is that the Museu Particular does not work with the past that is no longer in use, but with the present invisible and susceptible to being forgotten.

I explain.

A ethnographic object , according to the professor of Social Anthropology José Luis Alonso Put in the catalog of the exhibition Appliances, "it fulfills the functions for which it was created; when that function disappears, it can become a witness to the collective memory of the group"

"The society to which he has belonged continues to see in him a foundation on which part of its recent memory rests, and as such it is treated and appreciated in the museum or in the exhibition", he points out. However, Ponga continues, the objects, "When they leave the context in which they were created, when they are separated from their function, even if it is to go to a museum, they lose part of their essence. Because (...) its essence, beyond form, lies in the action in which they are made to participate at every moment. The museum immobilizes what was created to be mobile, deprives of life what had to be alive.

And this is where the anthropology professor introduces the great hero of this story, the savior of those objects: the museologist. "The museologist becomes the new author of the object, since with him he creates new languages and metalanguages intended for the new users, the visitors."

"The museum and the exhibition become nurseries of ideas, of theories of messages that the museologist launches so that they are understood and captured by the public", he adds.

This text, written by Ponga 20 years ago, is more contemporary than ever as the perfect definition for the role of Alex Rebollo and Ana Andevert in their museological project. Because the Museu Particular is a veritable nursery of ideas and metalanguages about objects that are still present for us today but that, at any moment, can become past. And this happens without us noticing. For example, with the clothespin.

This is how they manifested it in one of his Instagram posts: "The washing machine killed the public laundry only a few decades ago. Will the dryer do the same for the clothespins?"

Using the publications of this social network as a contemporary Power Point (by the way, another "object" that defines our society and that seems to be slowly falling into disuse, although there are those who want to rescue it as an artistic and narrative tool), the Museu Particular argues the hypothetical disappearance of the clothespin, explaining the case of the United States, where the rise of the dryer caused the closure of the last wooden clothespin factory in 2003.

Regarding this, Alex Rebollo explains that, in that country, "drying in the air is frowned upon. A house with visible clotheslines lowers the price of it and the houses around it "and he refers to the documentary Drying from freedom to explain that its use is seen as a symbol of poverty in the United States.

In this way, through Instagram posts and Twitter threads, the Museu Particular throws at us different questions and reflections derived from the objects that we use in our day to day almost without being aware of it (This thread on the hygienic tampon deserves a special mention).

When Alex Rebollo is asked about what keys to our society are you discovering, his answer is full of elusive investigative reality: "you should ask me this in a few months, when we have removed all the objects".

However, as a result of this question, he is able to connect with one of the first reflections that he has made so far: our obsession with the immediate. The use of social networks, the immediate accessibility to information through the omniscient smartphone, makes us want instant solutions to questions that take time to answer (if they can be answered, of course).

In relation to this, Rebollo mentions one of the objects that will appear later, in the month of August: a postcard. An object that symbolizes an authentic "revolutionary gesture in our society, where everything has to be controllable and immediate: sending a paper object that may not reach its destination".

Another key that Alex has observed since the beginning of his investigations is the sacralization and desacralization of objects by the mere fact of passing through a museum (and that he himself felt in his flesh with the experience of the fork).

This has its origin in that, as he himself explains, "We are fetishists, we keep things that apparently make no sense for us to keep, but because they are associated with memories." This leads him to a conclusion that connects directly with the thought of José Luis Alonso Ponga: " material heritage does not exist, but has the immaterial values that we associate with it".

At the beginning of the 20th century, the famous anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski made the following reflection "The ties between an object and the human beings who use it are so obvious that they have never been completely overlooked, but neither have they been clearly seen." But of course, he never got to know the Private Museum of L'Espluga de Francolí.