Louise Glück: a Nobel for the epic of the intimate

“After everything happened to me, / emptiness happened to me” writes Louise Glück in her poem End of Summer from The Wild Iris. A poet who is the antithesis of the omnipotent writer, the man with attributes or the thunderous gods that are often considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature and whose delicate, austere and transparent voice has slipped like an intruder into the list of winners a year (the fateful and confined 2020) that perhaps required, above all, a literature of intimacy.

For all those who once again placed at the top of this Swedish Miss Universe Murakami (they will never give it to him), Kundera, Cormac McCarthy, Zagajewski or… Javier Marías , his name has been an absolute surprise.

They didn't even have her on the women's short list. After all, she is not sophisticated in language and thought like the poet who is on everyone's lips, Anne Carson.

Perhaps she does share with Margaret Atwood some of her ruthless diagnosis of human nature, but Louise Glück does so from the most absolute minimalism, very far from the spectacular nature of the best-selling novels of the Canadian and focused on the family microcosm. She is not the voice of a people like Guadeloupean Maryse Condè, who was the first in the pools.

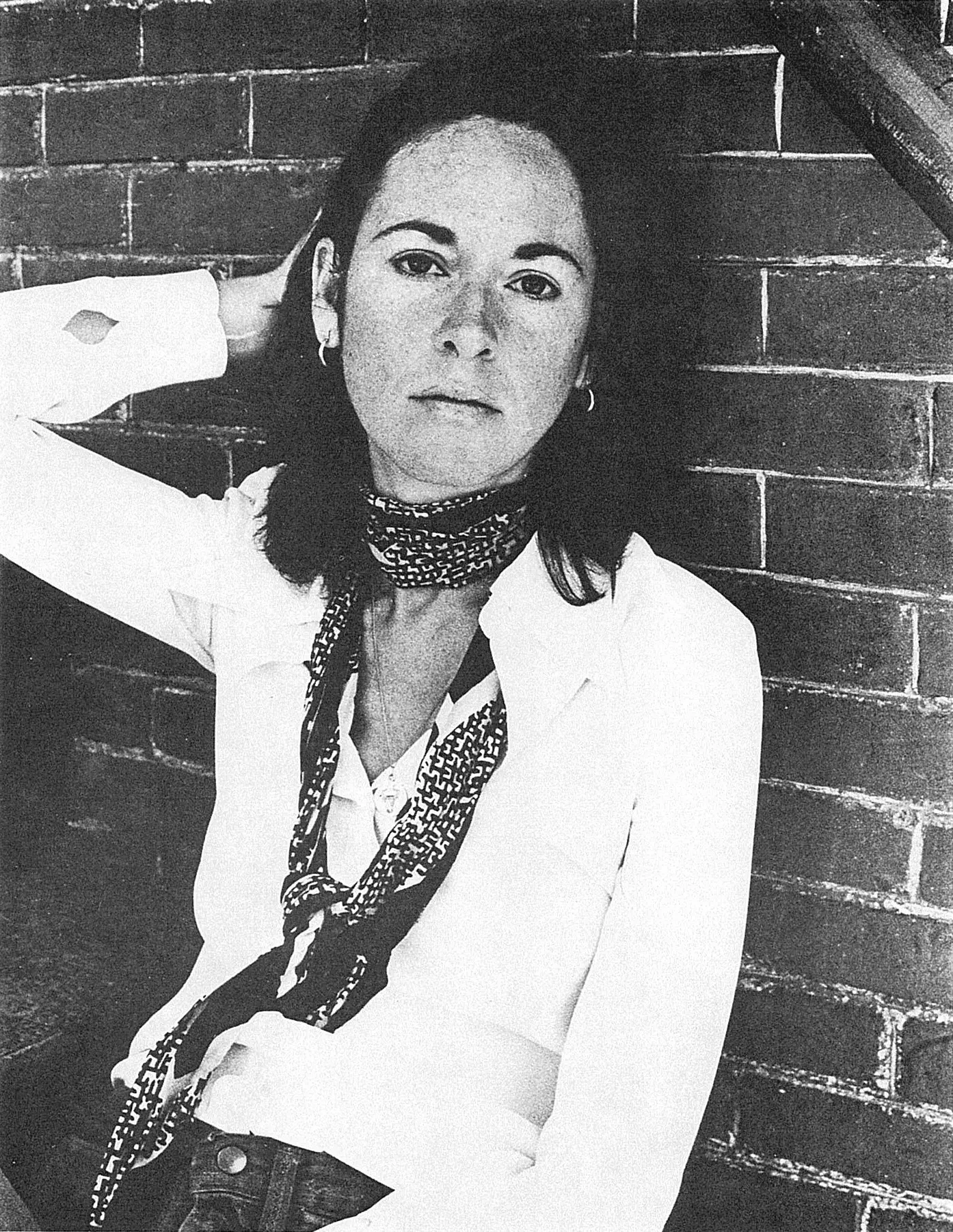

Louise Gluck in 1977

No, rewarding Louise Glück does not compensate any historical debt, since she is white, privileged and writes in English. By choosing her, the Swedish Academy has opted for the confessional and narrative poem, for stark self-absorption, for the dialogism that North Americans have cultivated so much and so well.

Louise Glück was born in 1943 in New York City and raised on Long Island. She had a sister who died shortly before she was born. “Her death of hers allowed me to be born”, she wrote in her verses –always relentless–, and she often describes herself in her poems as a girl and a woman who has spent her life seeking her mother's approval.

to her father, that he had helped bring the precision knife (better known in Spain as a cutter) to market, she defines him as a worldly man with buried literary ambitions and which is impossible to approach.

In her poems there is also a sister who is rarely an ally and almost always a rival. And of course her husband with whom she talks in that wonderful poem, The most sincere desire, which begins by saying: “I want to do two things: / I want to order meat from Lobel’s / and I want to throw a party. / You can't stand parties. You do not support any / group of more than four people.

During her adolescence she suffered from anorexia (“I stopped eating to kill my mother,” she said in an interview) and at 16 she nearly starved to death. A theme that appears in a corner in all of her work: the passion for form, the almost transparent and its price. Her ambivalent and acrimonious relationship with her mother. (“You haven't been completely perfect either – she writes in Penelope's Song –; with your troubled body / you've done things you shouldn't / talk about in poems”).

Her formal education was sporadic and she never graduated. At that time she spent seven years in psychoanalysis and a brief period at Columbia University. So we could say that she graduated from the New York school of life: that is, Freud, Emily Dickinson, and Jewish guilt.

Because in Glück's verse one, one actually, she is always her own worst enemy. Although the poet usually uses irony as a firewall from pathos or raw pain and interposes masks or characters, usually from the Bible, mythology or fables to distance herself from what is told, there is never any self-indulgence in the story. “I became a criminal by falling in love./Before that I was a waitress./I didn't want to go to Chicago with you. / I wanted to marry you, I wanted your wife to suffer./ Does a good person think this way?/ (…) Now it seems to me / that if I felt less I would be / a better person”.

Her poems are like letters written to herself. With a transparent language, sometimes laconic, without preciousness, she dissects her biography without hardly mentioning the context, going to the very core of the links, which are sometimes suspended in an object or a thing; in a detail that is excision.

Because Louise Glück is a master of the scene, she who suspends herself in an indeterminate place; anchoring epiphanies to everyday ceremonies, more like an atmosphere than a memory or recount.

Because unlike other confessional poets of the Anglo-Saxon tradition, Glück does not magnify himself in her defeats or in the cruel exercise of the damage that she has perpetrated. (of which male authors often sing alcoholics and futile mea culpa).

No, the epic of this woman is that of a very common intimacy: her sister's jealousy, the simulacrum of the happy family, the charming but sneaky father, a loving and castrating mother at the same time; the constant conjecture of the erotic life of the couple, which excludes us; the splitting of the other (the other) that is never reached… “The beloved does not need to be alive. The beloved lives in the head, ”she writes in Meadows or “The beloved identified with the ego of a narcissistic projection. The mind was a subplot. He did nothing but chat”, in Averno, my favorite book among all his.

Louise Glück at her Cambridge home

Sometimes the one who speaks in the poem is a flower, a poppy or a lily. Sometimes it is Hades who speaks, sometimes Persephone, sometimes Telemachus, or Circe; sometimes the mother's daughter, sometimes the son's mother. Sometimes the interlocutor is God.

But in them (behind them) it is always Glück. A woman who eludes the center, but is everywhere, like oxygen; capable of sustaining life, but at the same time flammable, dangerous and caustic.

Of course, the writer also has her detractors. In 2012 the critic Michael Robbins in LARB (Los Angeles Review of Books), he said that “Glück’s main weakness – which mars all her books to some degree – is that she too often gets so ruled by her feelings that she forgets she has a mind. If she wasn't aware of this tendency, she would be insufferable. Instead, she is a great poet with a minor rank. Each poem is the passion of Louise Glück, starring the pain and suffering of Louise Glück”.

In Spain, the litanies of Glück's intimate life have ardent defenders both in the publishing house Pre-Textos (which has published eight of her books) and in the poet and critic Martín López Vega (who was the one who told me about it for the first time in 2004, when he was a bookseller at La Central).

In the wonderful blog that he had in El Cultural, Rima Interna (when blogs were what they were) López Vega wrote in 2011: “Louise Glück's poetry is one more branch of the tree that unites, in the poetic tradition, intelligence and compassion. The one that makes us better and helps us to better inhabit what we call "human beings".

And she is right. To read it is to enter into the truce of this world to stop deep, to absorb himself with what continues to happen to us and haunts us: the mourning for a dead father, the disappointments of love.

"At the end of my suffering / there was a door," she writes at the beginning of The Wild Iris. Or “I was young here. I rode / on the subway with my little book / as if to protect myself from this same world: / you are not alone / she said the poem / in the dark tunnel ”, in Averno.

And so it is, the tunnel is dark and the state of exception (of uncertainty) an exhausting tightrope walk, but there is a little book, or two. There is a poem or two. You are not alone. The rest is noise.

THREE POEMS BY LOUISE GLÜCK

Burnt circle. Ararat (Pre-Text Ed.) Translation by Abraham Gragera.

my mother wants to know

why, if I hate so much

the family,

I founded one and took it forward. She didn't answer him.

what she hated

was to be a girl

not being able to choose

Who to love.

I don't love my son

the way I thought she would love him.

i thought i would be

the orchid lover who discovers

red trillium growing

in the shade of a pine

and he doesn't touch it, he doesn't need

own it. But I am

the scientist

that approaches that flower

with a magnifying glass

and he won't let her

even if the sun draws a circle

burned around

of the flower Thus

about,

my mother loved me.

I must learn

to forgive her,

since I am unable

to spare my son's life.

Siren. Meadows (Ed. Pre-Texts) Translation by Andrés Catalán.

I became a criminal by falling in love.

Before that she was a waitress.

I didn't want to go to Chicago with you.

I wanted to marry you, I wanted

that your wife suffered.

I wanted her life to be like a play

in which all parts are sad.

Do you think a good person

in this way? I deserve

May my bravery be recognized.

I sat in the dark on your front porch.

It was all very clear:

if your wife didn't let you free,

It was proof that she didn't love you.

If she loved you

Wouldn't I want you to be happy?

Now it seems to me

that if she felt less she would be

she a better person. She was

a good waitress,

she was capable of carrying eight cups at a time.

I used to tell you my dreams.

Last night I saw a woman sitting on a dark bus:

in her dream she cries, the bus she rides

she walks away from her. With one hand

she says goodbye; with the other caresses

an egg carton full of babies.

The dream does not suppose the salvation of the maiden.

A myth about delivery. Averno (Ed. Pre-Texts). Translation by Abraham Gragera and Ruth Miguel Franco

When Hades decided that he loved that girl

he built her a replica of the earth;

everything was the same, even the meadow,

but with a bed

All the same, until the sunlight,

because for a young girl it would be difficult

go so quickly from light to total darkness.

She thought to introduce the night little by little,

first as shadows of leaves that flutter.

Then moon and stars. And later without moon and without stars.

Let Persephone get used to it, he thought,

in the end she will find it comforting.

A duplicate of the earth

only there was love in him.

Isn't love what everyone wants

He waited long years,

building a world, observing

to Persephone in the meadow.

Persephone, the one he smelled, the one he tasted.

if you fancy something

you want them all, he thought.

Doesn't everybody want to feel at night

the beloved body, compass, pole star,

hear the calm breathing that says

I'm alive and that also means:

you are alive because you hear me,

you are here, by my side; and that when one turns,

does the other turn?

That's what the dark lord felt

looking at the world that was

built for Persephone. He didn't even think of it

that there could not be sniffed.

Or eat, that's for sure.

Fault? Terror? afraid to love?

He could not imagine such things,

no lover imagines them.

He dreams, he wonders what to call that place.

He thinks: The New Hell. After: The Garden.

In the end he decides to call himself

Persephone's childhood.

A dim light shines on the well-marked meadow,

behind the bed. He takes her in her arms. He wants

tell him: I love you, nothing can harm you

but believe

which is a lie, and in the end he tells her

you are dead, nothing can harm you,

what you fancy

a more promising, truer beginning.